Half the Sky is the name of a women’s movement that works on gender issues in developing countries supported by America’s department of international development. This gender rights group is trying to get the censor board to introduce a warning every time a woman is hit or physically abused on screen.

The activists will write to the information and broadcasting ministry and the Central Board of Film Certification, seeking a different “rating” for films that show men abusing women. They are determined to get the censor board to make a pop-up warning mandatory that would state: “Warning: The film contains violence against women. Violence against women is a punishable offence.”

Frame Her Right is the name of a 90-second video that these activists have put together which was launched online on 8 March to coincide with International Women’s Day this year, but it has become viral only over the last few weeks. The video is a collation of footages from several mainstream Hindi and South Indian films that show women being slapped, hit, thrown against a wall, groped or slammed to the ground.

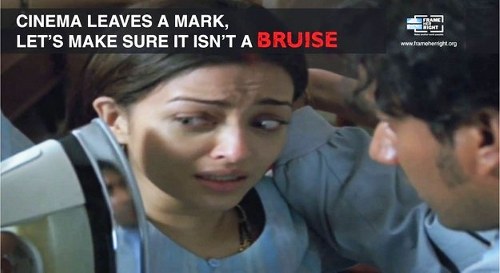

Scene from Frame Her Right documentary.

The film clips are intercut with graphics that state: (a) 50 percent of men say that women enjoy it; (b) 51 percent of women ignore it; (c) 32 percent of women say it proves manliness, (d) 95 percent of women feel threatened by it and (d) 70 percent experience it at home. The source and details of this data, however, are not provided.

Many people from the film industry are aghast and shocked at this move. While that in itself may not be reason enough to deride the movement or the film, there are certainly many unanswered questions that arise from watching this video:

Why is there an ominous silence about the status of documentary films dealing with violence against women where very often, scenes of violence are graphically depicted from real life? Would the pop-up apply to documentary films too?

What about public service advertising on television such as the one currently being shown called Boys Don’t Cry where a man is shown twisting the arm of his wife whose face is already brutally bashed up? Should the pop-up warning feature in such cases within a one-minute ad intended to spread public awareness about domestic violence?

Why are the clips picked from films that are so dated and not from more recent ones?

Why do the individual clips of films speed past at jet-like pace before each clip can register on the mind of the viewer?

Why do the titles of the films not feature as captions which would have made it simpler for the viewer to understand the implications?

Some of the clips one could recognise are from Insaf Ka Tarazu (1980), Darr (1993), Daamini (1993) Agni Sakshi (1996) Shakti: The Power (2002); there were a couple more that this critic could not recognize because of the rapid pace of the film where scenes telescoped into one another.

At the end of it, one feels that while it purports to tackle a grave issue, it is far from being a well-made film that makes its point lucidly. Therefore, one cannot help but feel sceptical about whether appropriate authorisations were taken before using the clips from the concerned people.

The YouTube page for this video supported by USAID states: "The Frame Her Right campaign aims to end domestic violence by creating a more gender-sensitised cinema that places women in a positive light, rather than exploited and exploitable roles. In addition to trying to change the portrayal of women in cinema, Frame Her Right works to challenge the unjust and unequal conditions that perpetuate violence against women."

What is important to note is that in the film clips chosen to send this message, none of the male characters perpetrating violence against women have been romanticised either in characterisation or in portrayal. They are clearly depicted as negative characters, or behaving negatively, or as psychologically diseased.

Agni Sakshi has been plagiarised from yet another Hollywood film Sleeping with the Enemy (1991), starring Julia Roberts in the original. The husband, played by Nana Patekar, who tortures his wife, is a psychopath. He is not portrayed as the hero because instead of trying to rescue a damsel in distress, he is actually the cause of her torture, humiliation and captivity. This could have been happening in real life. If cinema reflects life in some way or another, directly or indirectly, then why not demonstrate that depiction of life on film? What good would a pop-up warning serve within this scenario?

In Shakti: The Power, Nana Patekar is a different kind of feudal, fascist, killing dictator who runs his own fiefdom and therefore, a pathological case whom no one would bestow with the label of ‘hero.’ The film is a loose Hindi adaptation from a Telugu film, which again was based on Betty Mahmoody’s Not Without My Daughter (1991). The book described Betty’s real life escape with her daughter from the hands of her tormentors who wanted her dead but also wanted her daughter to be left with them. While the film was a badly made one which did not have the impact it wanted to create, it too tried to bring across through cinema, a real-life story of violence on a woman.

Viewing violence within a larger frame

The argument of the activists who are pressing for a statutory warning on screen is entirely focussed on the physical violence inflicted on a woman, depicted graphically on screen in a particular scene. But what about the mental, emotional and psychological violence on women?

B.R.Chopra's Nikaah (1982) tried to examine the victimisation of the woman within marriage, depicting a kind of invisible violence that is more threatening, scary and dangerous. Nikaah, a film with a Muslim setting, critiqued the use and abuse of a woman by two successive husbands in her life. In their eagerness to demonstrate their ability to 'give' rather than to 'receive,' they use the woman, an educated young Muslim beauty who sings well too, as the stake to lay bets on.

When her first husband divorces her, she finds it almost impossible to get a respectable job because the men take nasty potshots at her divorced state. When she finally arrives at a newspaper office for freelance assignments, the editor does offer her some assignments but also falls in love and marries her. That is the end of her journalistic career. Will the angry young women ask for a pop-up warning for such films too?

Poster of movie Provoked (2006).

Jagmohan Mundra made Provoked (2006) from the real life experience of Kiranjit Ahluwalia, a Punjabi wife, whose only option for escape from an extremely abusive and violent husband was to kill him. She was married to a Punjabi migrant to Southall in London who beat her up, bashed her and impregnated her whenever he came home from work. She was imprisoned for years and then freed through the good offices of an NGO backed by a public outcry among women for her release.

This was a film that had to be made. If cinema’s function is to inform, educate, entertain and bring about social change, Provoked fulfills all but the function of ‘entertaining’ its audience. A pop-up warning in this film would have defeated the very purpose of educating the audience – both men and women.

Imagine a film like No One Killed Jessica (2011) with pop-up warnings every other minute throughout the footage. Kahaani (2012), another woman-centric film, is filled with brutal, cold-blooded violence by the woman herself in the end. The beginning depicted a different kind of violence. So, what kind of pop-up warning should it have used?

Mardaani (2014) shows graphic violence both by both sexes on each other. Does this equalise and justify the man-woman relationship, in which each can be as violent as the other? The same rule applies to the recent film NH10 (2015) filled with extreme violence indulged in by men on weaker men and women and later, by the central protagonist, a woman, on men. If these films were to carry the pop-up warning, would it not appear melodramatic, or even redundant, within a situation where men and women are both capable of gruesome violence?

And finally, the last but most pertinent question for the movement to consider – should documentary filmmakers, who are committed to filming and documenting reality for the mass audience, use these pop-ups? Many of them are making documentaries on atrocities on women spanning the entire spectrum of violence against women from eve-teasing to molestation through rape, domestic violence, sexual harassment and murder. How many ‘different’ ratings can censors create for these different varieties and manifestations of violence? How many pop-up warnings can be used in a documentary film of say 60 minutes?