Mohsina, Afroza Khatun, Aminul Islam and Barun Biswas – if you are wondering what these names have in common, they are all crusaders united by a single common agenda – stopping violence against women. Their tales – inspiring in some ways and shocking in others – come alive in Naam Poribortito, a film that was premiered at the Cinema of Resistance Film Festival earlier this year at Jadavpur, Kolkata and that is now on its screening journey at different festivals and organised screenings, drawing accolades everywhere.

Naam Poribortito (Identity Undisclosed) is a 50-minute documentary that focuses on the unrelenting spate of rapes across the state of West Bengal over the past decade or more. The debut film of journalist-turned-activist Mitali Biswas, the film takes an objective look at rape, has victims talking straight into the camera on their circumstances and leaves it to the viewers to draw their own conclusions.

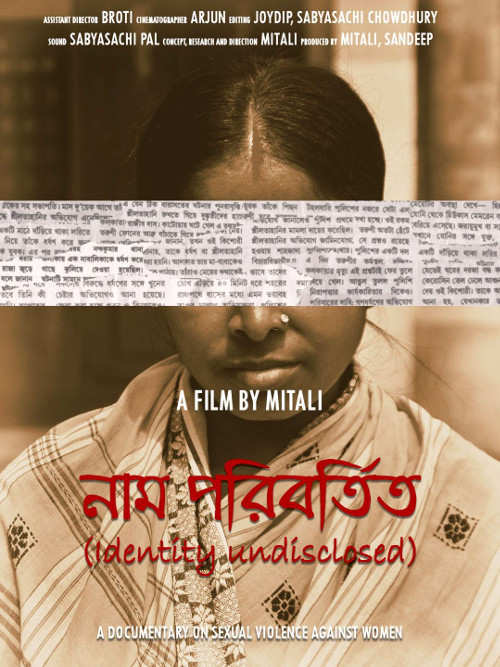

Mitali Biswas, director of Naam Poribortito (Identity Undisclosed).

Layer by shocking layer, the film exposes the realities and aftermath of rape and abuse in rural West Bengal through a well-researched narrative filled with statistical data, interviews with activists, lawyers and victims, newspaper clippings and stock shots of shocking scenes and statements. According to Mitali, “Naam Poribortito tries to identify the role of society and administration behind rape, through a few incidents which took place in India, mostly in West Bengal in the recent past.”

The tales within the tale

Naam Poribortito narrates the stories of various women, mostly belonging to the lower socio economic strata, who have been subjected to rape and molestation at some point in their lives ‐ either within the four walls of their home or on the battlegrounds of political power. The circumstances and even the denouements vary, but they all highlight the constant threat and vulnerability to sexual violence and repression faced by women in grassroots India.

So, for example, we hear the story of Mohsina who approached the village Panchayat for a job card so that she could get the 100 days of work promised under the NREGA, “I went to enquire after the allotment and was held captive at home because they said it will reach me at home and I need not go to the Panchayat office or even step out of home. The panchayat pradhan wanted to have sex with me. I drew courage from within myself. I had a sickle to chop vegetables. When he came to attack me, I felt I will die anyway, but I will kill him too,” says Mohsina.

Her seventeen-year-old son says, “My mother had done a brave thing by fighting her would-be rapist. In the society within which we live, protest means death. She was certain she would die but that did not deter her from taking that bold step.”

A survivor and her family talk after the first screening of the documentary. Pic: Shoma Chatterji

Another victim says that a man from the ruling party threatened her that he would not only rape her, but would parade her naked through the village streets and rape her in public. “I had stepped out early in the morning at around 3 for my ablutions. Can’t we have the liberty to do that?” she asks angrily.

Afroza Khatun, social activist, says, “Women must fight at two levels – one is the fight with the outside world against rape and other humiliation. The other is the fight within oneself against the social conditioning that creates guilt in the minds of victims that make them try to justify the wrong done to them.”

Afroza’s words ring true when one hears some of the other reactions vented on screen on the issue of rape. An elderly woman says that girls get raped because they do not listen to their parents, dress and behave in any which way. Another woman airs a similar opinion when she asserts, “Parents should take care of how their daughters dress when they go out. Look at the way some of these young girls dress. How can you blame young men if they are tempted by these ways of dressing?”

A young man driving a car says, “If a man and a woman are in love, it is a different story. But men visit bars and now girls want to go to bars too. They mingle with several men and it does not suit women to behave in this way. So, they alone are to be blamed for being raped.”

The overriding tendency of society to blame the victim leads to another very pertinent question and one that led to the title of the film. A rape survivor interviewed for the film asks why the names and identities of the victims should be changed or hidden in media reports, when they are the ones who have been the target of abuse, and not the criminals who raped them.

So, Mitali opens her statement with digitalised and fragmented faces of the victims discussed in the film but after the film ends, the faces of all victims, except minors and a very little girl of three, are shown beside their correct names.

The late Suzette Jordan, who had been raped in a moving cab in Kolkata and who came out voluntarily to reveal her identity at a time when the media had been referring to her as ‘the Park Street rape victim’, is also shown in the film. “Rape has nothing to do with class – of the rapist or the victim. In our society, anyone can rape anyone and justice is absent,” she says.

Where culprits roam scot free

The absence of justice is borne out by a few other instances showcased in the film. Rashmoni was raped and left unconscious in Nandigram and her rapists are roaming free till date. A little girl of three-and-a-half was raped by Subhash Roy, an aged man in the neighbourhood who subsequently absconded with his wife. The girl, when questioned by the filmmaker, shows no realisation of what has happened to her. When asked what she would like to be when she grew up, she says, “Police, so that I can bash up everyone.”

Mousumi Koyal, Secretary of the Kamduni Pratibad Mancha says that the chief minister of the state did nothing to bring justice to the rapists and killers of Shipra Ghosh, the Kamduni victim who was gang-raped by hoodlums on her way back from college. Kamduni is a village that lies around 20 kms away from Kolkata.

Her angry mother says into the camera, “The administration does nothing when men tear off the flesh of girls like dogs to feed themselves.” The still-grieving father says, “No one makes a cup of tea for me now or serve me puffed rice when I come back from work. Why do we educate children? So, that they can take care of parents when they grow up…”

Mousumi adds that their trip to meet the President of India proved futile. The President neither asked them about the Kamduni rape, nor did anything to have the culprits nabbed. “We have no clue why we were given an audience with the President,” she adds. Some of the victims’ brothers have been given jobs by the ruling party. “In poverty, a job can silence all voices of protest,” says a sad Moushumi adding that their fight goes on, come what may.

Advocate Jayanta Narayan Chatterjee points out that dragging court cases for a long time dissuades and discourages rape victims who do not wish to attend the hearings anymore beyond a point in time. The number of fast track courts is not enough to take on the burden of rising crimes against women.

The price of standing up against violence

The dark realities of women portrayed in the film take on an even grimmer hue when one hears of the fate of courageous crusaders such as Barun Biswas and Aminul Islam.

Poster of Naam Poribortito (Identity Undisclosed).

The former is almost a local legend in Sutia, a small village in north 24 Parganas, West Bengal, about 60 kms from Kolkata and the last village before the Bangladesh border. Many of the villagers are undocumented migrant workers. In September 2000, the village was inundated by floods in which around 99 percent of the local population lost their homes. Following this natural disaster, the villagers’ threats from the local tyrants Susanta Choudhury and Bireshwar Dhal escalated sharply.

What began as relatively small incidents of extortion snowballed into something grave and critical with casual rapes committed everyday on every woman in the village. Not a single girl or woman in the village was spared by these two men and their gang.

This rule of terror went on unabated between 2000 and 2002. There were at least 80 gang rapes over a period of 40 days. The police, the law and the medical fraternity became mute witnesses to these cases. Pushpa, a resident of Sutia narrates the case of one Lakshmi who was taken by the goons every night from her home to be raped: “Not a single doctor in the village was prepared to treat her.”

In August 2002, a young man named Barun Biswas founded the Sutia Protibadi Mancha and appealed to the girls and women to come out and protest because if they did not, the country would remain backward forever and there would never be a solution to their problems. "If we cannot protect our sisters, mothers, daughters and wives, we should not be living in a civilised society. If we lack the courage to take on the rapists then we deserve more severe punishment than the rapists," Biswas thundered at a meeting in Sutia Bazar to coax people to rise against the goons.

Thousands responded to the call (many relatives of rape victims) and the Pratibadi Mancha. Their efforts rid Sutia of the rapists and resulted in the ringleaders being jailed, but Biswas himself was gunned down ten years later on July 5 2012. His associates are keeping his voice alive in Sutia today.

The film does not have the scope or the space to elaborate on Barun Biswas’ story, but it does trigger curiosity, anxiety and shock among viewers who are familiar only with the photographed portrait of the young Biswas hanging in the homes of every resident of Sutia village.

Another sad story is that of Aminul Islam, a young man who sought to come to the aid of a 16-year-old rape victim. The girl had been repeatedly raped by Shahzada Baux under threat. After about a year, she put her foot down and complained to her aunt who told Aminul. The latter took her to the Karaya Police Station in Kolkata.

Two police officers took her to a separate room and asked her to withdraw her complaint. They forced Shahzada’s wife Nilofer to charge Aminul with theft in writing. The case of theft was later changed to robbery while Shahzada Baux roamed around freely in the area, pressuring the girl to withdraw her complaint.

On 3 December 2012, Aminul set himself ablaze in front of Karaya Police Station alleging harassment by the police. He left a suicide note for his parents naming three policemen and Shahzada accusing them of having driven him to his end. Shahzada was arrested the following day but Aminul lost his battle with life and passed away on 1 January, 2013.

While the detailing in some of these cases is a bit blurred and confusing, it is a direct, socio-political commentary on the situations that have prevailed for many years in pockets of West Bengal.

The broader picture?

A lot of statistical data intercuts the narrative of the film, functioning as a repeated reminder about the state of things in the entire spectrum covering violence against women. For example, the film reminds us that in India, 93 women are raped every day, on average. In 2012, a total of 24,923 cases of rape were reported. In 2013, the number went up to 33,707. These figures do not indicate the unreported cases.

The film also shows clips of protests following the brutal rape and killing of Nirbhaya in Delhi in 2012. But neither these nor the graphic cards harking back to the brutal rape of Manorama Thangiam Chanu in Manipur and detailing the features of the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act 1958 really fit in well in this hard-hitting film.

The maker might have used the larger picture in order to focus on the prevalence of rape on the national stage and the lack of justice for victims. But this partly detracts from the intensity of crimes against women in a state popularly extolled for its cultural history, intellectual achievements and artistic creations.

More than anything else, Naam Poribortito exposes the underbelly of a state where irrespective of the party in power at any given time, little time, space, effort and judgment are devoted to prevention and redress of crimes against women. Opposition parties are equally responsible for these evils and the conspiracy of silence is broken only before and during elections.