In the last forty years, Mahasweta Devi wrote twenty published collections of short stories and close to a hundred novels, primarily in her native language Bengali. She championed the cause of 25 million tribal people in India, who belong to approximately 150 different tribes.

Her writing reflects the ugliness, squalor and misery in the lives of the tribal people and indicts Indian society for the indignity it heaps on its most oppressed constituents. Yet of her voluminous work that covers different perspectives of fictionalised history, slave labour (Bharat Mein Bandhua Majdoor) and on the tribal pockets of West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh and Odisha, only a handful of directors have made films based on her work.

Her world in writing and in lifestyle was too difficult to enter, imbibe and translate without knowing, understanding and internalising the struggles of the marginalised adivasis – the Hos, the Mundas, the Oraons, the Shabars and the Santhals she wrote about. Their social structure is different from our own. The language they speak in, the food they eat, their lifestyle, their customs and rituals, the clothes they wear or do not wear, the sources of livelihood and even the gods they worship are a mystery to mainstream people like us and the filmmakers.

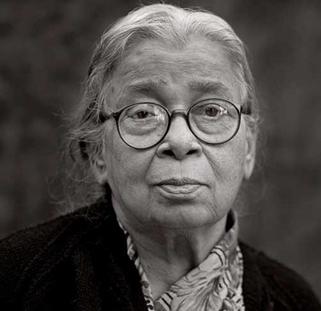

Mahasweta Devi (14 January 1926 – 28 July 2016). Pic: Wikimedia commons

Mahasweta held up in detail, an alternative history that India has but few know or those who do, hardly care about. She was one among the few Indian regional writers who drew national and international attention to the plight of the Indian tribals.

Adaptations of her literary works into films

Among national filmmakers, the three exceptions have been H.S. Rawail who made Sunghursh (1968) a period costume drama based on Mahasweta Devi’s historical fiction Laili Aasmaner Aina, Govind Nihalani who adapted her famous novelette Hazaar Chaurasi-r Maa translated in Hindi to Hazaar Chaurasi Ki Maa (Mother of 1084) in 1998, and Kalpana Lajmi’s film adaptation of Mahasweta Devi’s short story Rudali to Rudaali (1993).

Sunghursh, produced, directed and scripted by H.S. Rawail had a cast and crew difficult to compete with. Shakeel Badayuni wrote the lyrics set to music by Naushad, Gulzar wrote the dialogue with Abrar Alvi. The film had an enviable star cast led by Dilip Kumar and Vyjayanthimala as the star-crossed lovers with Balraj Sahni, Sanjeev Kumar, Jaywant, Ulhas and Sapru in negative roles, supported by Sundar, Deven Verma, Durga Khote, Sulochana, Padma Khanna and Iftekar all of who did justice to the responsibility they were given to perform well.

The story of Laili Aasmaner Aina was written much before Mahasweta Devi had stepped into her tribal world but still had a social agenda. Her works in fiction were often based on history and this was no exception.

The story and the film had all ingredients for a lavishly mounted period costume drama. Set in Varanasi, this fast-paced film talks of thugs, the killers who were a terror in Northern India in the 19th Century. They mostly belonged to priestly families but under that disguise, they would rob unsuspecting pilgrims of everything they had. Rawail, loyal to the original story addresses the loot that goes on at pilgrim centres in the name of faith. The film demonstrates how the ritual of sacrifice is misused for personal gain and how men compromise love for spiritual virtues – issues that are relevant even today.

The story moves along different levels and has several sub-plots from the refusal of the heir to accept and take on the profession of looting from his grandfather, vengeful rivalry between two leading families, the love between two children of these families destined to a tragic end - all blended well into each other through the intelligent craftsmanship of Rawail.

Govind Nihalani’s Hazaar Chaurasi Ki Maa perhaps come closest to the original story. But, he becomes self-indulgent by extending the original story in an attempt to give it a contemporary flavour which does not work at all and spoils the statement the story the film was trying to make.

Instead of retaining the end of the original story by Mahasweta Devi, Nihalani brings it to contemporary politics and shows the protagonist Sujata (Jaya Bachchan) running an NGO with her mellowed husband in the city. This robs the story of the tremendous power inherent in the character of the mother who is trying to find out why she could not understand her son. Besides, Jaya Bachchan, perhaps not familiar with Mahasweta’s Bengali writings, despite being a great performer, somehow retained her charisma as Jaya Bachchan. The star-actress keeps peeking out from behind the character very often specially in the closing scenes that are Nihalani’s personal extension of the original story.

This story marks Mahasweta Devi’s turning from a personalised, middle-class, discomfort-within-comfort zone to focus on the Naxalite movement in West Bengal and its impact on an upper-middle class, sophisticated, high-powered, urban family of Kolkata.

This is brought through how the different family members react to the violent death of the youngest child Brati – a stunning debut by Joy Sengupta, whose death is shown only through the number 1084 tied to one toe. Sujata Chatterjee (Jaya Bachchan), is a wife and mother in her forties, who works in a bank. The reactions to the death by the rest of the family sets out to redefine her life and try to understand it in new terms from a different perspective through imaginary conversations with her dead son.

Another classic novel named Rudali was adapted by Kalpana Lajmi into a Hindi film. Professional mourning has a long tradition in parts of India and in Rajasthan in particular. Before the affluent dying man actually dies, he is left uncared for and neglected, often left to sleep in his own excrement. But once he is dead, the family gives him the grandest of funerals as an elaborate and ostentatious statement on the family’s so-called power, fame and wealth within the village or small town and as a prestige issue. Mahasweta Devi’s primary focus is the portrayal of the community life of Ganjus and Dushads who form the majority in Tahad village in the original story.

Though Rudali is a novelette, its powerful story covers a range of issues such as abject poverty, caste system and Indian funeral practices as well as the role of women in a strongly patriarchal society.

Kalpana Lajmi’s film adapted from this story remains loyal is spirit but fails in execution, presentation, approach and treatment. She chooses two very glamorous actresses of Indian cinema to play the mother and daughter, respectively – Raakhee and Dimple Kapadia whose starry glamour remains undisturbed despite the no-make-up look Lajmi invests them with. This defeats the very purpose of the film and story’s strong statement.

The music by Bhupen Hazarika imposes Assamese folk music on the Rajasthani ambience which works fine. But too many songs make it a musical and work against the film’s political statement. The male characters are equally important, as exploited and marginalised as their women are, when placed in the larger canvas of the social structure ridden by caste restrictions and taboos and Lajmi gives them adequate space.

Rudaali, the film, is an independent piece of work by Kalpana Lajmi while Mahasweta Devi’s Rudali, the story, is another independent piece of writing.

Other adaptations

Of the Bengali adaptations and the two small Doordarshan efforts by filmmaker Buddhadev Dasgupta, namely Arjun and Choli Ke Peeche, in Hindi, the less said of, the better.

Note that Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak did not ever adapt any of Mahasweta Devi’s story into film. Excellent mainstream filmmakers in Bengali cinema like Tapan Sinha, Ajoy Kar, Arabindo Mukherjee or Sushil Majumdar did not take up Mahasweta Devi’s work ever. Perhaps Mahasweta Devi's story settings, plotline and characters belonged to a world they were not familiar with, so they kept away from stories that were almost alien to their experience.

A few Bengali films have been made on her works but their quality is so poor that even DVD versions may not be available in the market. Shyam Benegal who adapted Dharamvir Bharati’s famous classic Sooraj Ka Satvan Ghoda into film, did not make any film based on Mahasweta Devi’s story.

Among her contemporaries in writing and in activism, Mahasweta Devi, through her literary works - novels, short stories, nonfiction essays, and as an editor and activist stands a class apart. Her grassroots dedication to the deprived goes beyond writing sympathetically about them from an urban ivory tower. She actually lived and worked with and for them in their own environment, and tried to see that fellow commentators do full justice to her works.