Years before Lakshmibehn married Govind Tadvi from the Adivasi village of Gora in the vicinity of the Sardar Sarovar dam in Gujarat, his family had been robbed of its jeeva-dori - its very means of sustenance - by the vagaries of development and the politics of water. Bedecked in her bridal attire, Lakshmibehn must have gone through the rituals of her wedding like any other young woman: starry-eyed and hopeful. That hope was soon extinguished.

Soon after she moved to her saasri, her dreams began to unravel a layer at a time, revealing a reality which she had to learn to battle every day of her dispossessed life. The grind of poverty, a yearning for justice, and a lingering hope for a saner future, now became permanent features of her life. But the feeling that seeped through her existence and wove together its threads, was perhaps, one of loss. An irrevocable, crippling, total loss.

When Lakshmibehn was still a child, her destiny was shaped by what Jawaharlal Nehru - in a moment of contemplation - called the "disease of gigantism". Nehru was referring to big projects including large dams, and pointed among other things, to the displacement they brought in their wake. He went on to advocate small schemes which, he emphasized, had much greater social value. Ironically, this was the same Nehru who poetically christened large dams the "temples of modern India". In any event, Lakshmibehn's future could not be salvaged from the debris left behind by a dangerously misdirected notion of development.

Much before her wedding, Lakshmibehn's future husband's family was deprived of their agricultural land and the plot on which their house stood in 1961, to build infrastructure for that icon of development in modern India: the Sardar Sarovar dam. When Lakshmibehn married and moved to her husband's house, she learnt that their agricultural land had been taken over by the Gujarat Government by paying the family a meagre Rs.80 per acre. She also learnt that the land on which their house stood no longer belonged to them.

Not even eligible for resettlement according to the Government's policies, and with nowhere to go, no occupation other than agriculture to pursue, the family resolutely refused to move. On their field, the dam builders erected three godowns to store cement for its construction. Lakshmibehn remembers as many as sixty trucks coming to her village every day to transport cement. They wouldn't even have space to stand, she recounts. Day and night, the movement of such trucks made Lakshmibehn's life extremely difficult. Whatever little the family sowed, in the small bit of land they had left over adjoining the house, wouldn't grow.

In neighbouring Vaghadiya - a village on the main road to the dam site - as many as three hundred trucks would arrive daily. Loading and unloading of heavy cement bags was the only occupation available to men to earn a livelihood. Crushed under the weight of an inhuman toil, many died an early death. Their wives - unable to leave their little ones behind and travel for majdoori - started selling alcohol at home. Afflicted by the hazards of rampant unemployment and alcoholism, the village soon went to seed.

When Lakshmibehn moved to Gora as a bride in the mid-seventies, a new road was being constructed in the village. With their fields swallowed up by the cement godowns, the family soon began to labour on this road. Each worker earned a ridiculously paltry Rs. 2.50 a day.

How did they manage? They couldn't, she answers. But what could she have done? Her in-laws and two of her sisters-in-law were also dependent on the couple. Lakshmibehn had to search for greens in the forest. She had to make do with lal juwari - grain of an inferior quality. She remembers buying a tiny bottle of oil and using a few drops of it every time to make it last as long as possible. You think about how difficult it must have been, she throws the question back, as if she shouldn't have to answer it. Tum socho.

After two decades of battling a debilitating penury, Lakshmibehn's husband Govind was employed as a chowkidar in Kevadia Colony: a town with offices and accommodation for the engineers and staff building the dam. Today, he earns Rs.6000 a month, of which Rs.1000 is saved in his provident fund. The five-thousand rupees that he brings home must support everyone in the family, including the couple's unemployed son, his wife and their children.

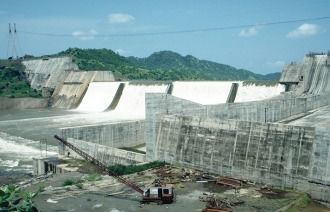

"We should be resettled according to the same policy as the submergence oustees, with five acres of land and a house plot. They have lost their livelihoods to the reservoir of the dam, we have lost ours to its colony. So where is the difference?" (Picture: The Sardar Sarovar dam under construction. - Photo courtesy International Rivers.)

Lakshmibehn's son Harilal, in spite of his best efforts, has never had any work by way of which he could have supported his wife and three children. Had their land not been lost to the cement godowns for the construction of the dam, Harilal could have earned his livelihood by farming. Now, he is left with absolutely nothing to do. When a nala was being dug in the colony, he too became a labourer. Like his father, he worked as a chowkidar at an ashram school for a month. Beyond these fleeting chances of earning something, anything at all, he has always been unemployed. "What work will he do?" says Lakshmibehn. "There is no work here."

In the early nineties, after years of relentless struggle as part of the Narmada Bachao Andolan (NBA), the Government made a new offer to the nearly 950 families in the six villages uprooted by the colony including Gora: cash compensation of Rs.12,000 an acre up to a maximum of three acres, and a house plot. Officials told the villagers bluntly: Take this money. And leave. Once and for all.

Lakshmibehn's family, in spite of their trying circumstances, refused. They knew that they couldn't even have rebuilt their house with the cash they were offered, leave alone buying replacement land. "We haven't taken the money", she declares emphatically. "We should be resettled according to the same policy as the submergence oustees, with five acres of land and a house plot. They have lost their livelihoods to the reservoir of the dam, we have lost ours to its colony. So where is the difference?"

As the construction of the Sardar Sarovar dam nears completion, Lakshmibehn's hopes for her long lost land have been gradually rekindled. For the past six years, the cement godowns on her land are lying empty. Why doesn't the Government remove them and return the unused land to her family? She attends meetings organized by the NBA, she stands up to police harassment and repression. But Government officials have never even bothered to inform her of their plans. "How will they inform us?" she asks, somewhat surprised. "No one ever comes here."

Even more bad news

The Government, on its part, has fresh, ambitious plans, fully capable of extinguishing the embers of hope which Lakshmibehn has somehow managed to keep alive. The year before last, new surveys were conducted in Gora, following which two gates were constructed. The sign on one of these gates reads: Heritage Village, Rajpipla Forest Department. But Lakshmibehn can't read what it says. Her family was never told the purpose of the gates. But by now, they know that such developments can only mean bad news.

Of the land acquired for the project colony and related works, a large part remains unused. But instead of returning this land to its rightful owners, the Gujarat Government now has an entirely different plan. A spectacular tourism project with private sector participation is now coming up, on these very lands once acquired for a 'public' purpose. The proposed features in the first stage of the project include restaurants, a food court, hotels, a rose garden, camping and adventure sports, among others.

A fresh wave of police repression has been let loose on the villagers, to facilitate the progress of the project. At an NBA meeting that Lakshmibehn attended last year, she witnessed her fellow protestors being beaten and forced into police vans. Such repression, however, does not deter her from standing her ground.

In this new scheme of things, with the Government's plans afoot for welcoming urban consumers to a tourist paradise at Kevadia Colony, Lakshmibehn is viewed as a mere obstacle, even a nuisance. In a developing, growing India, she must keep her truth, her loss, her hope, all to herself. For even if she speaks out, with her reservoir of courage and perseverance, who will hear her story?