Police firing and subsequent deaths at Nandigram in March had shocked the nation. The central and state governments received a clear warning of the dangers of forcing an arbitrary SEZ policy premised on an unjust land acquisition law on the people. But seen from a dalit perspective, the violence at Nandigram was the reflection of a deeper tension that has been building up since the local residents claimed political autonomy of the area, and the state administration made a pre-meditated effort to put down the dissent with force. Police records also show that the majority of victims did indeed come from the Scheduled Castes. This is the story of Nandigram, beyond the immediate waves of the events of 14 March.

A fact-finding team from the National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights (NCDHR) gathered details through visits to Nandigram on 16 and 17 March and later from 20 to 25 April. The team engaged in conversations with the victims and their families.

Build up

On 2 January the Nandigram Block Development Office (BDO) announced the seizure of land in the area for the creation of an SEZ. The announcement was made by postings on the BDO office door and the district magistrate's office. On 3 January a group of villagers, incensed by the news, marched on the Garchakrebia Panchayat office. The Panchayat members called the police to intervene and remove the protestors. The police arrived and lathi charged the protestors. The villagers responded by torching two police vehicles and attacking the Panchayat office.

In the ensuing violence 11 people were killed in clashes between the police and party cadres on the one side and protestors on the other. CPI(M) party members were allegedly driven from the area by the angry villagers. In the ensuing violence, one female party member was allegedly raped. The party members stationed themselves in neighbouring Khejuri and allegedly fired on protestors from across the dividing canal.

Government action

With this background the West Bengal state government decided to act to 'restore order' in the area. Prasad Ranjan Roy, Home Secretary of the West Bengal government, announced at Writers Building (seat of the WB Government) on 9 and 12 March 2007 that there would be police action in Nandigram. The exact numbers of how many police were mobilised are not clear - conservative figures put the number at 700 whilst others claim as many as 3,000. Along with standard lathis the police were armed with .303 rifles and semi-automatic insas assault rifles. The police were poorly equipped with non-lethal crowd dispersal equipment, an issue they have not addressed since then.

It appears that there was dispute amongst the police about the role that the CPI(M) cadres should play - whether they should form a rearguard to occupy the villages after the crowd had been dispersed or whether they should not be allowed in at all. Disturbingly, in the end, they formed the vanguard alongside the police force and what is apparent now were allowed to carry their own arms, guns as well as swords. It has even been stated by eyewitnesses that they were dressed as policemen. This decision was apparently taken by senior policemen, who decided that their knowledge of the area would be valuable to the expeditionary force.

14 March 2007

What is certain is that the legal requirement for a magistrate to be present and sign an order permitting the use of lethal force was not met. What is also apparent from all accounts is that the police gave protestors very little time and effective persuasion before opening fire especially considering the sheer number of people and therefore the logistics in clearing the crowd. All evidence points to a readiness and anticipation of opening fire with live ammunition on the crowd.

After the first rounds were fired, eyewitnesses state that as the protestors fled, the assailants chased them down the road. Survivors spoken to report seeing the brutal murders, including the beheading of a child. Our observers, who entered the village as late as 17 March, say that the streets had remnants of human blood on them for two kilometres from the site of the initial confrontation. Locals claim that 100 to 150 people were killed and party cadres were seen placing dead bodies into the back of lorries. The police suggest that 14 people were killed. Official figures differ greatly from what we gathered from the survivors, prompting suspicion amongst our observers that either party could be wildly exaggerating.

Subsequently a variety of reports have emerged suggesting serious questions about the integrity of the official figures. These include the number of rounds found in the area with also a variety of bullet types. Body parts have been unearthed, most notably the charred remains of a body in the Sonachura area. Meanwhile many families report missing relatives; some report seeing their family members falling to the police bullets. An arms cache with 800 live rounds belonging to CPI(M) members was also found in a brick kiln. Whilst the confrontation occurred, party cadres cordoned off the area to prevent press and supporters of the villagers into the area for quite some time before allowing entry.

Our observers spoke to some of the survivors and relatives in hospital. Kajili, attending to her badly beaten son in Nandigram hospital, told our team amidst tears, "I saw a child being beheaded. I could not see it anymore, and ran from there." Other accounts taken by our team highlight wide ranging incidences of beatings and sexually harassment including that of a 55-year-old woman, who on all accounts was not a threat to 'law and order' or to practically anything or anyone. So traumatised was she that her relatives had to recount her tale for her. "She had fallen down on the spot; bahini (party cadres) people beat her badly, later because they did not prefer raping her, they put a stick in her genitals and mutilated them." The team also visited a building where women had been gang raped, still littered with items of clothing.

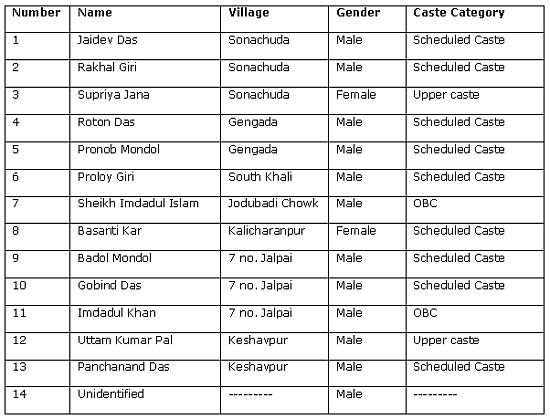

Confirmed deaths as per police records

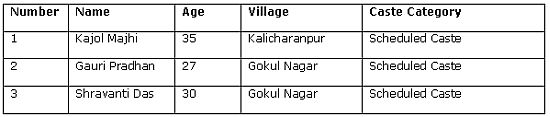

Women gangraped as per police records

Government response since the atrocities

The state government put forth a variety of responses. Most notably they have withdrawn the proposals for the area and the SEZ will most probably be built in Haldia, the neighbouring district. A CBI (Central Bureau of Investigation) team was one of the first to mobilise and visit the area, sent there by the Supreme Court in Kolkata. The CBI report highlighted key facts already presented here, including police and 'outsider' collusion and the fact that the firing was 'unprovoked'.

The CPI(M) has responded with a variety of statements varying from denial, to counter attack and most recently limited efforts at a reconciliation process in the area. Most bizarre are statements about a U.S. collusion with protestors.

Background: SEZs and the Left

The CBI report highlighted key facts already presented here, including police and 'outsider' collusion and the fact that the firing was 'unprovoked'.

•

Rights denuded in wordy forest

•

Riots and wrongs of caste