In some parts of the country, pastoralism contributes significantly to livelihood and wealth - usually in terms of milk, wool, meat, dung, bone and other things of value that people extract from their herds. According to a conservative estimate, pastoralists in Rajasthan rear around 16 per cent of the country's sheep, 13 per cent of goats and 86 per cent of the camel population. Rajasthan's livestock economy contributes 8 per cent to the national GDP in the sector.

At a time when the climate crisis has become a top agenda for global leaders, a study by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and the United Nations Environment Program revealed that pastoralism has the potential to play a key role in transitioning to a green, environmentally sustainable, global economy. But making that happen is far from easy.

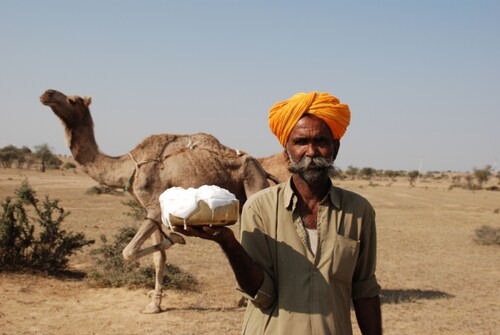

"It is because of our camel we have been able to survive in this harsh desert temperatures," said Sumer Singh Bhati, a camel herder in Samvata village in Rajasthan's Jaisalmer district. "Everything of the camel is useful, its milk, skin and dung. But these days, camel rearing has become expensive and unprofitable. There is inadequate government support for herders. And the pandemic has been a great blow to us, making it hard to to sustain our herds and families," lamented Bhati who owns around 200 camels.

Pandemic halts more than movement

The tale of Bhati mirrors the worsening situation of around four lakh pastoralists in Rajasthan who depend on camels as a mainstay of their livelihood. However, after Covid-19 hit the country, these pastoralists have encountered numerous challenges such as social stigma, lack of grazing land, poor access to veterinary care and government apathy.

"You can see there are too many livestock grazing on the same lands," said Ram Narayan Raikia, who lives in Jodhawar Ki Dhani in Palli district. Raikia added, "Our camel and sheep are struggling to find adequate pastures. They are not getting sufficient nutrition and becoming weak day by day. Many have already died of diseases that we have no clue about. It is all happening because of the pandemic."

Raikia has a valid reason to blame Covid-19 for his misfortune. The pandemic induced lockdowns and travel restrictions imposed by the state government coincided with the seasonal migration of thousands of camels and other livestock such as goats and sheep. Pastoralists undertake annual long-range migrations from the drier parts of Western Rajasthan to the greener pockets of Punjab and Haryana during the summer months, beginning in late March and ending in July with the onset of the monsoon.

This year, due to covid travel restriction, pastoralists couldn't make this trip. Some of them transported herds of 200-300 animals to faraway pasture land by truck. "It cost a lot of money," complained Raikia, adding "Our livestock are not familiar with such type of transportation. They remained stressed/panicked throughout the journey."

Traditionally, as the pastoralists passed through an area, the local farmers would allow herders to graze their animals on their lands after harvesting crops. In return, farmers got dung and droppings from herds which helped increase soil fertility. But now pastoralists are facing hostility from local communities, who look at them with suspicion and accuse them of spreading the coronavirus. According to a 2020-research study conducted by ActionAid in five states including Rajasthan in 2020, "...fear of transmission of the virus has not just led to prohibiting the herds from grazing but has also seen harassment of the pastoralists."

There is also another shift. "Instead of organic manure, farmers are now applying chemical fertilisers," said Hanwant Singh Rathore, who works with a Palli-based NGO called Lokhit Pashu Palak Sansthan (LPPS). This is jeopardising the subtle balance of inter-dependence between farmers and herders and thus exacerbating animosity against each other, pointed out Rathore.

Another major challenge includes fewer buyers of camel milk in the local market. One herder told me over the phone that he was not able to transport camel milk during the pandemic-induced lockdowns. Even now when the lockdowns and travel restrictions have been relaxed, the demand for camel-derived products has not yet fully revived. Civil societies working in Jaisalmer district allege that the reducing numbers of tourists as a result of fears about coronavirus has also affected the marketing of camel-derived products.

Camel milk, the white gold of the desert. Photo credit - Dr Ilse Köhler-Rollefson.

Camel milk was traditionally not sold, in fact, but in recent years it has become important to the livelihoods of pastoralists. But the virus has hit this too. "Before the virus came, I was able to sell 20-30 litres of camel milk per day to local hotels and tea vendors. I was earning around Rs. 1000-1500 per day. Tourists from other states and even foreigners used to drink milk. But now, there is no such demand," said Harvinder Singh, who supplies camel milk in Jaisalmer.

A law for camels, not camel-herders

The state government's actions in recent years have also not helped, say pastoralists and activists. Rajasthan enacted the Rajasthan Camel (Prohibition of Slaughter and Regulation of Temporary Migration or Export) Act in 2015, designating the camel as the official state animal. The new law also restricted herders from inter-state transportation of the animals. "This Act has devastated the economy of herders," said Rathore who works with LPPS. The ban in trade across the state border has drastically slashed the animals' price.

For instance, about a few years back, a healthy five-year-old camel would sell for around Rs.70,000, whereas now it can fetch only Rs.3000. The desperation amongst the herders has gone to such an extent that they are selling a six-month-old camel calf at Rs.1000-1500.

Cattle fairs at Tilwara and Pushkar used to draw tens of hundreds of people from across the country. But these days, the breeders are struggling to find adequate buyers in these once popular animal fairs. For herders, who were not able to travel long distances beyond the state borders, these fairs use to provide a platform to sell their animals. But the new Act discourages buyers from other states, who might otherwise visit these fairs and buy animals from the local herders. In 2011, there were 8238 camels brought to fair for sale, but this figure went down to 3298 camels in 2019, according to data shared by the Rajasthan Animal Husbandry department. "The Gehlot government should allow the sale of camels outside the state," appealed Bhati, the camel herder.

Hard times have hit the annual camel fairs. Picture credit : Annapurna Mellor.

Hard times have hit the annual camel fairs. Picture credit : Annapurna Mellor.

Some positive steps

Even before the pandemic, there have been several chronic challenges for camel herders in Rajasthan such as lack of organised market, depleting natural resources and pastures, inadequate access to vaccination and veterinary services. However, amidst this crisis, some civil society organisations in Rajasthan are coming forward to help camel herders revive their livelihood.

Since September, LPPS, with financial support from international donor agencies has been supplying camel milk to school children at a government secondary school in Guda Joba village of Desuri tehsil of Palli district. "We have seen a 15 per cent increase in student attendance after we began providing camel milk," said Danesh Purohit, principal of the school. Camel milk has more iron and vitamin C than cow's milk and regular consumption will improve health among the students, emphasised Purohit.

Rajiv Tomar, a community health worker in Bikaner district said, "Last year, I attended a training programme at Jodhpur organised by National Research Centre on Camels. We were told about various health benefits from camel milk. After attending the training, Tomar started sensitising rural communities in Bikaner tehsil about the multiple health benefits of camel milk. This has resulted in creating a greater demand for camel milk in many villages including Himtasar, Jalwali, Dalya, Naibari, etc. Access to fresh fruit and vegetables often remains a challenge for marginalised communities in Rajasthan. Camel milk can serve to make up for vitamin deficiency among children and prevent anaemia among women.

|

More could be done. "We have been requesting district administration to include camel milk supplies in Anganwadi centres but of no avail yet," said Pramita Devi Singh, a community woman leader in Jaisalmer district. Government should enhance access to camel milk to children, pregnant and lactating women, Singh appealed.

The future of camel herders and other pastoralists in Rajasthan largely depends on the ecological restoration and sustainable conservation and utilisation of natural resources. Many issues that pastoralists face intersect, and therefore what they need is an integrated approach to pastoralism, agriculture and silviculture, especially in the semi-arid and arid regions. Pastoralists themselves should also be actively involved in the policy formulation and designing development programmes.