As millions of people move from villages to cities, they create rising demand for land in urban areas, for a variety of uses. The competition for this land often prices poor people out of urban life, especially because much of the land in urban areas is owned privately. In Ahmedabad, a town planning scheme has tried to address and overcome this, and the experience of the city is instructive for many others.

The World Resources Institute, as part of its series on equitable living in Indian cities, studied the Ahmedabad TP Scheme, and drawn attention to the important lessons from it. Its report, authored by Madhav Pai, Anjali Mahendra and Darshini Mahadevia, concludes that the scheme has been transformative in that it has contributed to the generation of land for public purposes.

This mechanism was put in place through the Bombay Town Planning Act of 1915, when Ahmedabad was under British rule, but was more widely and effectively used after the 1999 amendment to the present legislation, the Gujarat Town Planning and Urban Development (GTPUD) Act of 1976.

The TPS is a land pooling and readjustment mechanism that allows the city to appropriate land from private landowners for public purposes, such as roads, open spaces, low-income housing, underlying utility infrastructure, and other health, education, and community services. Rather than acquiring the lands, the development authorities create a pooling scheme in which land-owners participate, voluntarily giving up a percentage of their holdings in exchange for development in the area. This allows planning agencies also to carry out large projects without much capital, which is often in short supply in cities.

Private landowners benefit in two ways: via compensation payment for land acquired (after deducting the costs of infrastructure, referred to as betterment charges); and the rise in land prices after the planning authority invests in trunk infrastructure. Landowners receive a reduced area of their original land after the appropriations, and the appropriated lands are then reserved for various public purposes.

This is a quicker way to appropriate land than the process currently stipulated through the 2013 Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (RFCTLARR) Act, a national act that is applicable to both rural and urban areas. The RFCTLARR Act is considered time consuming to implement, yet it provides for a more fair and transparent process developed with farmers’ participation, a framework that did not previously exist.

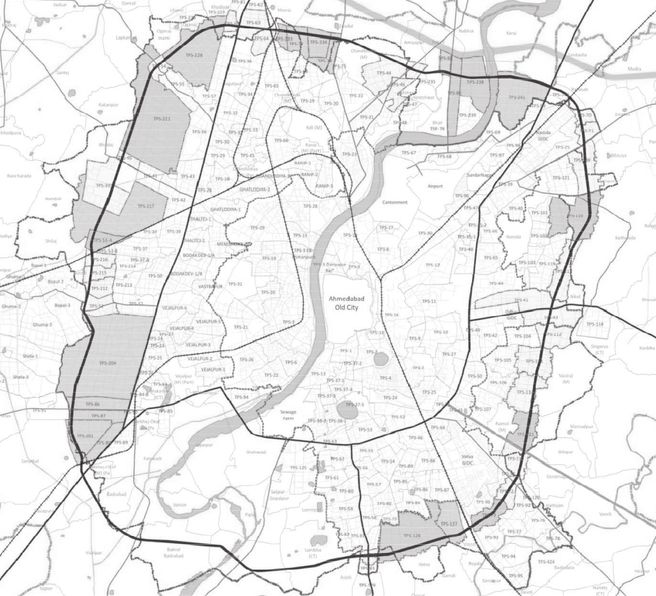

The ring road around Ahmedabad was developed using a Town Planning Scheme.

WRI's research paper reviews the evidence on whether the TPS mechanism has enabled transformative change with equitable outcomes in Ahmedabad, and if so, how. The paper identifies important triggers of transformative change in the city, examines the roles of key enabling and inhibiting factors in terms of urban governance, finance, and planning, and discusses challenges that remain.

The key findings from this research were:

- The TPS has enabled more equitable allocation of urban land, allowing Ahmedabad to obtain land for public purposes such as low-income housing, open spaces, roads, underlying utility infrastructure, and social amenities. This has had transformative outcomes, including allowing the construction of 33,000 dwelling units under the Basic Services for the Urban Poor of the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission.

- Although the notion of equity is embedded in this process, it is also limited by the state’s ability to prioritize public needs over private land rights, negotiate with original landowners, and be flexible about accommodating the existing informal sector.

- While the TPS is a progressive step over eminent domain, it does not include the participation of all stakeholders, namely tenants and informal occupants, in the negotiation process.

- The TPS has faced challenges including time delays, lack of financing, and opposition from farmers in locations distant from the urbanizing periphery.

- Despite these limitations, the TPS provides a tool for better planned and serviced urban development. It has allowed Ahmedabad to overcome key barriers that many Indian planning authorities face in obtaining lands for roads and other amenities and to avoid the haphazard, unserviced urban expansion that characterizes most Indian cities.

With nearly a million people moving into cities and towns each month, and with a very large portion of economic activity now centered in urban areas, their effective management and governance will be key. The Ahmedabad experience is potentially useful to many other cities, as they try to balance competing demands for land for different uses.