Not too long ago, in April this year, Hindustan Times reported the discovery of “headless torsos of two Dalit labourers – Nanjaiah (60) and Krishnaiah (47)” at a banana plantation off National Highway 209. Attempts to find out whether the perpetrators responsible for the death of Nanjaiah and Krishnaiah have been identified do not yield ready or easy information. But the same report did mention that while the news of the beheading didn’t garner much attention in the newspapers, Sanghasena, the district President of the Samata Sainik Dal that had been leading the team of investigators was of the opinion that the beheading were clear cases of witchcraft.

News items such as this, which are examples of the continuing, rampant obscurantism concerning superstition and related practices, are often relegated to the inner pages of newspapers in some small, obscure corner. But they call for an urgent exploration of the status of anti-superstition legislations across India.

Public opinion and legislation

Legislations are not exclusive answers to prevailing social injustice, but in the last few years, public discourse-driven interventions in legislation have demonstrated several positive changes, for example in the case of the Lokpal Bill, the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act 2013 and the repeal of Article 66A of the Information Technology (Amendment) Act, 2008. These and other cases have shown that public opinion, if consolidated and sustained, can create interventions in the state machinery and change laws which curb individual rights.

However, demands for legislation to protect people from obscurantist exploits have not generated much public engagement, nor has the state taken any effective steps to curb the occult practitioners from claiming anymore innocent lives. The status of the superstition bills in India bear this fact out.

Comparative analysis of the anti-superstition bills in India

There are existing national laws such as the Drugs and Magic Remedies (Objectionable Advertisements) Act, 1954 of the Parliament of India which prohibits people from advertising drugs and remedies that claim to have magical properties and considers advertising products claiming to do so as a cognizable offence. State level legislations are also present in Bihar, Jharkhand, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh to prohibit witch-hunting. In Karnataka, there are acts such as the Karnataka Devadasis (Prohibition of Dedication) Act, 1982 and the Karnataka Koragas (Prohibition of Ajalu Practice Act, 2000).

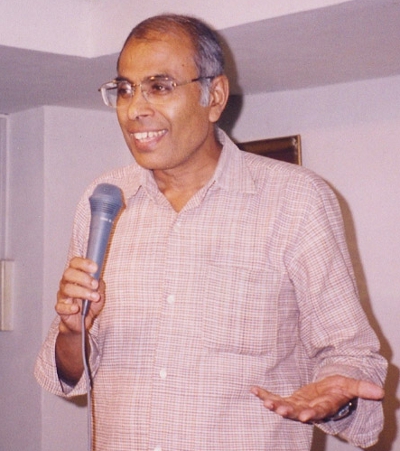

Maharashtra, however, is the first state to have passed a comprehensive legislation to protect people from being exploited in the name of superstition. Doctor and rationalist Narendra Dabholkar who founded the Maharashtra Andhashraddha Nirmoolan Samiti (MANS) in 1989, engaged in a decade long struggle challenging several superstitious practices, black magic and exorcism.

Narendra Dabholkar, founder of the Maharashtra Andhashraddha Nirmoolan Samiti (MANS) whose murder in Aug 2013 forced the Maharashtra govt. to promulgate the Maharashtra Anti-Superstition and Black Magic Ordinance. Pic: Wikimedia Commons

Originally drafted in 2003 by Dabholkar in association with MANS, the bill was not passed until 2013. It was only after Dabholkar’s murder on 20 August 2013 that the government succumbed to sustained pressure from MANS and other civil society organisations and subsequently promulgated the Maharashtra Anti-Superstition and Black Magic Ordinance.

The bill witnessed severe criticism from the Hindu Nationalist parties, such as the Shiv Sena and Bharatiya Janata Party, on grounds of being anti-Hindu. Extremist organisations such as the Hindu Jagran Samiti, Abhinav Bharat and Sanatan Sanstha also vehemently opposed the bill and were explicitly abusive towards Dabholkar.

While many of the aspects of the bill were amended by the Social Welfare Ministry of the Maharashtra Government before it was actually passed, it still remains an important event as it allowed the renewal of discussion on the adoption of a universal anti-superstition bill or anti-superstition bills in various states.

Following the lead of Maharashtra, Karnataka also proposed a bill in 2013 – the Karnataka Prevention of Superstitious Practices Bill, 2013. The Centre for Study of Social Exclusion and Inclusive Policy at the National Law School of India University, Bangalore was entrusted with the responsibility of drafting the Bill and it had initiated discussions among academics on the bill before submitting it to the government.

The Bill seeks to provide punishment for any person who promotes, propagates or performs any superstitious practice, entailing imprisonment for a term which shall not be less than one year but may extend to five years. It also includes provisions for a fine which shall not be less than 10,000 rupees but which may extend to 50,000 rupees. Additionally, the bill includes a provision for death penalty or life imprisonment for performing human sacrifice.

However, even after repeated suggestions, the bill has not been adopted. As in Maharashtra, in Karnataka too, Hindu groups have criticised and opposed the bill. In spite of official attempts from several quarters, such as the request by the current chief minister of Karnataka, K Siddaramaiah to pass the bill in the assembly or the call of the Vice president, Mr. Hamid Ansari to make the anti-superstition law a national law, the engagement from people representing different layers of the society has been minimal.

If passed, Karnataka will become only the second state, after Maharashtra, to bring in a law criminalising such superstitious practices. In Assam, chief minister Tarun Gogoi has called for the drafting of a law that prohibits exploitative practices, but no further development has been reported since. Kokrajhar and Jorhat districts still report high number of deaths due to superstitious practices.

A victim of witch-hunting in Assam. (Pic from India Together files)

According to a report in The Economic Times, “in the last decade alone, Assam has witnessed nearly 100 killings as a result of various social evils practiced by people inspired by superstition. According to police records, 21 cases of witch-hunting were registered in 2006, followed by seven cases in 2007, 10 cases in 2008, four cases in 2009, 11 cases in 2010, 29 cases in 2011 and 14 cases in 2012 across Assam.”

In yet another state, Tamil Nadu, shortly after the death of Dabholkar, DMK chief M Karunanidhi noted that the Centre and state governments should aim to adopt an anti-superstition law and include scientific temperament in school and college syllabi. However, here too, there has been very little concrete progress in that direction.

States such as Bihar (Prevention of Witch (Daayan) Practices Act, 1999), Jharkhand (Anti- Witchcraft Act, 2001) and Chhattisgarh (Tonahi Pratadna Nivaran Act, 2005) have laws to curb witchcraft, but Poli Kataki, a Delhi-based advocate opines that “the sentences prescribed and the paltry fines recommended in the state laws have so far proved ineffective in curbing this social menace” in these states.

The Rajasthan government has also taken the initiative to draft the Rajasthan Women (Prevention & Protection from Atrocities) Bill, 2011. The bill mentions that whoever maligns or accuses a woman of being a “Dayan or Dakan or Dakin, Chudail or Bhootni or Bhootdi or Chilavan or Opri or Randkadi” (all terms denoting a woman who practises witchery) will be punished with a prison term extending up to three years, along with a fine that can go up to Rs 5000.

The draft bill also includes proposals for stringent punishment if anyone uses “criminal force against a woman and/or instigates or provokes others in doing so with an intent to harm and/or to displace her from the house, place or the property, lawfully occupied or owned by her…” in the name of stopping “witchcraft” or “possession”. The punishments also include prison terms ranging up to 10 years and fines ranging up to Rs. 50000 for offences involving intimidation or torture based on superstitious discrimination.

However, the discrepancies in punishment, vague definitions of what causes harm that can be booked under the anti-superstition laws, the lack of inclusion of other occult practices apart from witchcraft within the ambit of the anti superstition laws and the lack of concern for guaranteeing victim protection have been some of the primary issues limiting the effectiveness of existing laws.

This has urged many activists, including the President of the Federation of Indian Rationalist Associations, Narendra Nayak, to rally for a uniform anti-superstition and blind beliefs’ act so that laws can be drafted more stringently, leaving no loopholes as evident in the laws in Bihar, Jharkhand and Chattisgarh.

However, more pressing is the need to question the absence of a rational collective, fighting to ensure that the basic human rights of citizens of the nation are not violated.

Weak attempts to fight the evil

There is a fine line between superstition and religion and treading that fine line is a challenging task. Godmen, heads of religious organisations and even ministers have exploited this fine line for their own vested interests. They have intentionally created an aura of “fright” around issues regarding religion, making it difficult for the public to not only understand religion sans superstition, but even making sure that critical discussions of anything remotely concerned with religion are stalled.

An important stakeholder is the larger scientific community, but in most cases, its members maintain an indifferent and apolitical stance towards issues of social relevance, adopting an ‘elitist’ position while distancing themselves from the general public. It has been no different in the case of the anti-superstition legislation.The scientific community could have been much more active in promoting science programmes for citizens, in disseminating knowledge and information, or using their academic training and privileges to question the stunts of godmen who aim to establish a strange correlation between events of significantly different categories.

In the absence of such efforts or engagement, groups with vested interests have channelised or stalled decisions and judgements to suit their respective agendas.

Misguided public opinion

Apart from the deliberate and convenient blurring of the distinction between superstition and religion, there has also been an intentional misrepresentation of the bill and its purview. This has shown how public opinion is now increasingly driven by a handful of people, and a proactive agenda-driven propaganda based on false information spread by different lobbies: the politicians, godmen and religious quacks. This has been further facilitated by the lack of active involvement from the larger scientific communities.

Many have also argued that the anti-superstition bill is in conflict with their individual beliefs and faiths. One needs to look at the actual drafting of the bill to understand that the bill does not, in any way, restrict or affect the religious beliefs, practices or faiths of individuals. The law intervenes only when, in the name of religion, individual beliefs are enforced or institutionalised and people are harmed, killed or forced to believe that certain practices are pious and hence mandatory to follow.

The bill aims to ensure that citizens are not exploited due to superstition and where it does happen, to provide people with an avenue, a mechanism, a process to hold people or organisations accountable for the act. Given the lack of access to authentic information about the draft law and transparent, informed public debate on the same, it has been impossible to get this across to a wider cross section of the people.

A possible resurgence of public opinion?

On the brighter side, there has been growing aspiration among one section of the population, including sections of scientists and researchers, to seek legislative and judicial interventions to uphold the spirit of scientific temper and to protect people from occult practitioners. Organisations such as MANS, Bharat Gyan Vigyan Samiti, working on science popularisation and inculcating scientific temper among various sections of the society, and a few scholars from the National Law School of India University are engaged in a long, sustained movement to spread awareness and organise public participation on this issue, both in and outside academic institutions.

After the recently concluded XVth All India People’s Science Congress, jointly organised by Karnataka Rajya Vijnana Parishat and Bharat Gyan Vigyan Samiti, Karnataka, the All India People’s Science Network passed a resolution and called for the consolidation of the progressive and democratic forces in all States and Union Territories in India to fight against obscurantism and exploitation.

Panel discussion on Anti-Superstition Bill during the 15th All India People's Science Congress held in May 2015, Bangalore. Pic: Bharat Gyan Vigyan Samiti

The criticality of public opinion

In all of this, it is important to recognise that the delay in engaging with the issue of superstition and in passing legislation to stop its malicious effects has dangerous implications for the public. It benefits no one except the lobbies with selfish interests and their associates in the political fraternity,

Godmen and religious quacks have routinely used tricks to say they are saving the community from witches, helping people who cannot bear a child, or providing remedies for incurable ailments. The people who engage in fraudulent superstitious activities or related propaganda usually get away with a clean chit by using religion as an alibi.

Narhari Maharaj Chaudhari, the secretary of Maharashtra State Warkari Mahamandal had stated that the Maharashtra Anti Superstition Bill is redundant as human sacrifice falls under the purview of the Indian Penal code. It is true that there are laws under the IPC which criminalise sexual abuse, harassment and human sacrifice; but then, what stops the concerned authorities from taking necessary steps when killings and sexual abuse are done in the name of superstition? Are abuse and murder fine as long as they can be carried out under the pretext of religious superstition?

The need of the hour is for the state to recognise the intent of the crime and if the intent is in violation of the directive principles of the constitution. It is also high time that we, as citizens, start discussing such issues and contribute in whatever little way we can to create the necessary awareness.

A small, significant intervention from civil society can help a child appreciate that a black cat is merely an animal and not an indicator of bad omen! A woman battling discomfort and pain during menstruation can receive more help and care instead of being kept in solitary confinement; an aged, elderly woman can be welcomed into the community instead of being excommunicated or lynched; people concerned about not being able to conceive a child can visit a doctor for alternative conception strategies instead of being sexually exploited.

Battling superstition needs, first and foremost, the proactive participation of all – society, the scientific community and elected representatives – towards ensuring safe lives and dignity for all citizens of India.