Saankal (2016, Hindi) is a film that is a classic example of strong content marred by bad making. But it scores in terms of shedding light on a cruel custom that is still practiced by Mehar Muslims in some Muslim-dominated villages in Rajasthan.

Directed by debutant director Dedpiya Joshii, Saankal which means “shackle” brings across the terrible truth of a concocted custom among Mehar Muslims in Rajasthan, which was created decades ago. This custom was triggered by unmarried girls remaining spinsters who had to be married off but there were no bridegrooms they could be married off to. Muslims of the Meher caste in Rajasthan's Jaisalmer and Barmer districts prefer to marry their daughters within the caste. Men are allowed to marry outside the caste, making it more difficult to find eligible grooms for eligible girls.

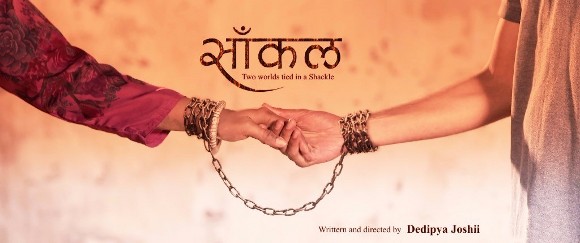

Poster of the movie Saankal. Pic: Pisceann Pictures

Why? The director says, “After the partition of 1947, some Indian villages became part of Western Pakistan. Marriages were arranged between families on either side for some time. But after a few years, political situation built impossible-to-cross blocks and families on both sides lost connections with their relatives across the border.

Consequently, the number of marriageable males went down and more and more girls did not get married for want of eligible young men. The option left for these unmarried girls, considered to be a social stigma for the families they belonged to, was either to remain spinsters or to marry very old men who died soon after.

By the time village council realised the disaster it was too late. Instead of uprooting the cause they passed another law in panic which they felt would be a solution to the problem – they decided to get these girls married off to younger boys in matching families. This worsened the position of both bride and groom instead of resolving the problem. As this meant that a 26-year old woman was married off against her will to a 11- year old boy. That is just half the story because this tale has an ugly, incredible twist one cannot imagine in 2016.

After the marriage, the young girl in the film is persistently raped by the men in her husband’s family including the boy’s father, uncles and so on with the support of the other women in the same family. But there were problems. When the girl got pregnant, who would be considered the father of the baby? What would happen to the baby? What would happen to the bride herself? Going back to her parents was unthinkable within the community. She has to slog with backbreaking work during the day and at night men would enter the bedroom and rape her one after another.

The state administration is afraid of losing out on vote banks by trying to curb this custom that is a violation of human rights not only of young women but also of the boy child who is married off to a older women without understanding the implications and responsibilities the marriage brings. These marriages are in blatant violation of the Child Marriage Restraint Act but the police choose to turn a blind eye to these marriages.

According to the Child Marriage Restraint Act (1929) revised in 1978, the minimum legal age for marriage stands at 18 years for girls and 21 years for men. Hence this practice among Mehar Muslims grossly violates the rights of boys, while the woman is made vulnerable to being raped, molested and impregnated by older men.

The movie

Saankal narrates the story of one girl who grows to love her boy husband as he grows up but who cannot rescue her from her torture. She commits suicide. The story sounds very powerful but the film is that much weak in terms of performance, presentation, music, acting and technique. The only good thing about the film is its subject matter and the picturesque backdrop of Rajasthan. Kids like Kesar (11) and young girls like Abeera (26) became victims of this custom. The director and his entire team have tried its best to convey the evil effects of this tradition through the film.

Sadly, authenticity and research have been sacrificed in favour of glamour. The debutant heroine who portrays the main victim does not look like a rural Rajasthani girl with rustic features with her make-up and colourful dresses that look extremely fake and sound a false note whenever she appears on screen.

For a story filled with pain and tragedy, there is just too much of glamour added into the film and one fails to understand why the director and his team chose a mainstream strategy to make an off-mainstream film in terms of plot and theme.

Tanima Bhattacharya in a still from Saankal. Pic: Pisceann Pictures

Tanima Bhattacharya, who portrays the older wife in Saankal, has won the Best Female Lead award at the Indie Gathering at Cleveland, Ohio, USA in August 2015 along with the film bagging the Best Foreign Film Award. She went on to win the Best Actress Award at the Online Russian International Film Festival in October 2015, while the film won the Best Film Award.

The Shaan-e-Awadh International Film Festival, Lucknow in Nov. 2015, bestowed three awards to the film – Best Film, Best Actress and Best Director. Other awards are the Golden Award in the Foreign Film Competition category at California in January 2016, The Best Story Prize from the Kalyan International Film Festival, Maharashtra in February 2016 and the Best Film in the Women’s Section at the DFW Dallas South Asian Film Festival the same month and year.

Many very badly made Indian films are bagging awards at many film festivals in India and beyond borders even though they do not reach anywhere in terms of the quality of the craft of cinema such as story-telling, cinematography, editing, framing and most importantly, acting.

Is there any merit in the film festival and film awards?

Saankal is a classic case in point. But the questions that get raised in this context that also provide the answers are – do the films win in terms of the strong content they advocate, little known to festival juries across the world? Or, are the festivals themselves too marginal and invisible where better films do not take part and big banners do not evince a keenness to participate?

There are other films that do not merit even a release much less a viewing. One example is Alo Chhaya (2014) where the director Ananya Samanta has claimed to place on celluloid Sarat Chandra Chatterjee’s last short story which, however, turned out to be a twisted completely out-of-shape story of love reincarnated and reborn. It dealt with the sub-plot of a widow’s love for a young zamindar and won awards at International Film Festivals inspite of being a very badly made film.

Another film Hemalkasa (2014, Hindi) based on the life of Baba Amte and his wife who lived all their lives in Hemalkasa won the runner up audience award at the London Indian Film Festival in 2014. It was also shortlised among 300 films across the globe for the Best Foreign Film Award at the Academy Awards in 2015. It was a very positive film with strong content but had a very loosely created script and inspite of good performances by the two leads, could not be evaluated as a good film because the film craft was not up to the mark.

Madhurita Anand’s film Kajariya (2013) that dealt with infanticide and a woman forced to pretend to be a witch to kill female infants, had a very strong subject but the film released recently in India for a very short run apparently was made to appease foreign film festivals. It was among the three films that premiered in the Dubai International Film Festival in December 2013. It is a shoddily made film that revealed the director’s focus more on festival screenings and less on the quality of the film.

Film festivals are mushrooming nationally and internationally. There is no guarantee however, that these festivals will raise their standards in the future or even that they will be able to sustain themselves over time.

Many of the festival organizers begin with the aim of rubbing shoulders with the glitterari of the world of glamour and making quick money through the sponsorships attracted by these festivals. They appear to be fly-by-night operators who are here today, gone tomorrow. The same applies to the production houses that send their films to participate in these festivals.

Are these awards “bought”? Or are they really “won” on merit? These are questions that perhaps demand to be explored in greater depth.

In the meantime, let us remain satisfied with content. As this writer mentioned at the outset – there is so much to learn from.