If you have never heard of a film festival that does not charge any gate money for entry to the screenings, debates, or discussions, or, ask you to register to show your delegate card at entry point, then you must hear about this unique film festival that runs in different cities across the country as an annual event every year. Nor does it ask for sponsorships or donations or any other financial assistance and is run solely by a committed team of volunteers, old and young. They take turns to wait at the exit with a donation box where viewers are requested to put in whatever they wish to in order to cover some of the costs incurred.

This festival now christened the Kolkata People’s Film Festival (KPFF) is organized by People’s Film Collective (PFC), an independent, autonomous, people-funded cultural-political collective based in West Bengal. Formed in 2013, it believes in the power of films as a weapon of pedagogy of the oppressed as well as alternative media for people. PFC organises monthly film screenings in Kolkata. It travels in Bengal with films and significant videos. It’s members document movements and make political documentaries.

PFC brings out an annual magazine with excellent contributions from intellectuals, academics, media experts and film-makers called Pratiroder Cinema which translates as “The Cinema of Resistance” which is self-explanatory. The festival also brings out a very informative and well-drafted bulletin everyday besides organizing a well-categorised stall that sells important books on cinema and on social movements, and also DVDs, posters, art prints and so on.

The 4th annual film festival of PFC was held at Jogesh Mime Academy in Kolkata from 19th to 23rd January. Classic feature films made by famous filmmakers in the past formed a major attraction.

Screenings were classified under “Tributes”, “Dalit Movement Now”, “Justice Denied”, “Difficult Loves”, “Songs of Life,” “Working Lives”, “Our Cities”, “Songs of Rebellion” and “A Torn Subcontinent”.

New additions in the festival

This year, there were two very interesting additions that marked the expansion of the festival into related areas of human experience. One was a painting exhibition under the title “To Stories Rumoured in Branches” that was organized at a different venue displaying 63 original paintings by Rollie Mukherjee who was present to explain her works and how they connected to the festival’s theme of ‘people’s resistance’ .

A still from film Matir Moyna (2002). Pic: KPFF

The other addition is a section called “Little Cinema” that screened a few short films of interest to children and the late Tareque Masud’s beautiful feature film Matir Moyna (2002). The film opens around 1969 and ends in 1971. The building up of the narrative is centered on a small boy’s growing up in a Bangladesh small-town, with his father, mother and kid sister. His deeply religious father, Kazi, sends off Anu, a young boy, to a strict Islamic school, or Madrassa. As political divisions in the country intensify, an increasing split develops between moderate and extremist forces within the Madrassa, mirroring a growing divide between the stubborn and confused Kazi and his increasingly independent wife. Touching upon themes of religious tolerance, cultural diversity and the complexity of Islam, Matir Moyna brings in an universal appeal within a world being torn apart increasingly by strife and religious fundamentalism.

Sayantani, the moderator, introduced the festival to the children and this session, which was in the memory of Biren Das Sharma. The session on short films started with The Boy, the Slum and the Pan’s Lids (1995) by Cao Hamburger - a short film from Brazil about a little boy who ‘steal’ two pan lids, only to use them as instruments in a local band. We then moved onto Two Solutions for One Problem (1975) a film by Abbas Kiarostami, about friendships and solution exploring the choice between whether a problem can be solved by fighting—leading to an ’eye for an eye’ situation, or, whether it can be solved in a more peaceable, understanding manner.

Gaon Chodab Nahi (2010) by KP Sasi is a very moving music video comprised of a song in which Adivasis talk about their land, about lives which are slowly being taken over by multinational companies. They talk of the need to protect our environment.

The attentive children in the audience identified Birsa Munda’s statue in the film and spoke about who Birsa Munda was. Pistulya (2009), a Marathi film directed by Nagraj Manjule narrates the desire within a young boy who wants to attend school but cannot because he is victimised by the casteist and classist social structure he lives within and the film ends on a tragic note.

The session was marked by a talk Chhobir Golpo by Sanjoy Mukhopadhyay backed by clips from The 400 Blows (1959) and Aparajito (1956). Mukhopadhyay, who taught at the Film Studies department at Jadavpur University spoke about techniques used in film-making, the politics and jugglery of lights, camera techniques and equipment that goes on to create the magic and illusion of cinema, and about ways of seeing.

Resistance, protests and activism

The inaugural session comprised of two film tributes to two immortal figures in India famous in their own fields of art and literature and known for their activism through their works.

One was a 41-minute film Mahasweta Devi – Close-Up (2016) by Joshy Joseph which is exactly not a biopic though Joseph imaginatively weaves in tiny nuggets of Mahasweta Devi’s earlier life through an interesting conversation. This is a small part of an ongoing film he was making at that time called Journeying with Mahasweta Devi (2009).

The other was a 66-minute biopic on Ima Sabitri (2016) directed by Bobo Khuraijam. Talking about his experience of having journeyed with Sabitri Heisnam, Bobo Khuraijam said, “She is indeed an awe-inspiring personality. But at the same time, she is not someone who would not come down from the higher pedestal. She has the warmth of the mother, caring with everyone. That you can see in the film as well, how she mingles freely with each and everyone around so lovingly. She loves to talk. She loves to tell stories. And I love to listen.”

The section aptly labelled “Dalit Movement Now” was opened by Samata Biswas who introduced the audience to Dalit Camera—a movement that started in 2011 in Hyderabad, to document caste-based violence and marginalisation, which was not being shown in popular media. When solidarities were first forged between universities, Dalit Camera became popular in 2013 when interviews they had conducted after the Ambedkar cartoon issue were taken up by major news channels along with a few more critical interventions leading to debates.

A series of videos around topical issues such as Una, Malkangiri, and Justice for Rohith Vemula were shown. Dalit Camera bore witness to incidents around different cases and uploaded these videos on social media sites. The second video as a part of the Justice for Rohith Vemula had a song from the film Kabaali (2016) made by a Dalit director as the background score. The Malkangiri clip spoke about the Japanese Encephalitis case in Malkangiri and the connection between poor nutrition and the propensity for malnourished children getting the virus.

Flames of Freedom: The Ichchapur Declaration (2016) is a documentary directed by Subrat Sahu. The film documents the people-led protests—against caste based discrimination—in Ichchapur, an Adivasi village in the Kalahandi district of Odisha, only recently inhabited by Brahmins. The outrage from the Adivasis has prompted them to socially boycott and vow to root out Brahmanism. The director talked about the legacy of landlessness and the impact of development on landowners. Going Gonzo (2016) by Venkat Ravichander shows us the protests at Una which happened after Dalit men were trashed in broad daylight in Una, Gujarat. It shows how important it is for the Dalit community to be able to farm their own land and how lip service from politicians is seen as just that—lip service.

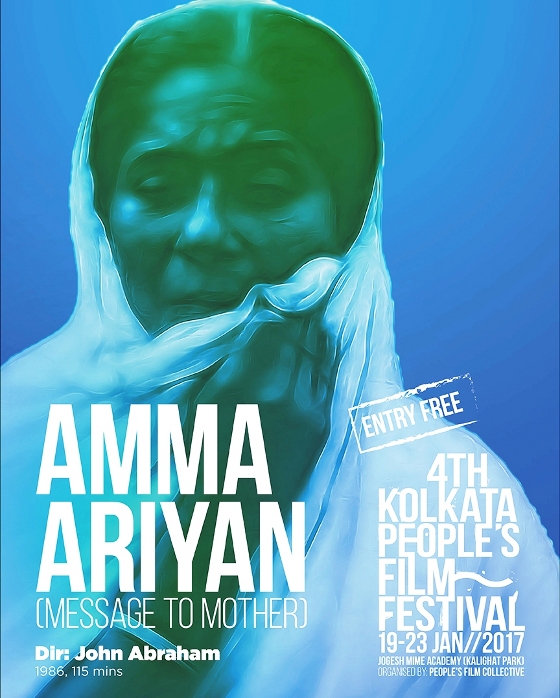

Poster of film Amma Ariyan (1986). Pic: KPFF

Day Two of the festival opened with the screening of Amma Ariyan (1986), a classic feature film directed by John Abraham. The story revolves around the incidents following the death of a young Naxalite, whose friends travel to the village where his mother lives to inform her of the death of her only son. The film is known for rewriting all the conventions of traditional filmmaking.

The second session had films clubbed under “Justice Denied”. The film screened was the powerful documentary, Voices from the Ruins: Kandhamal in search of Justice (2016), directed by KP Sasi. The film charts the course of caste and religion-based identity atrocities in Orissa especially focusing on the Kandhamal riots. Apart from showcasing attempts at saffronization, the film portrayed the desperate state most Adivasis, Dalits and Christians are in at present with the growing threats to their religious and cultural identity.

The third session aptly titled, “Difficult Loves”, showcased two finely crafted films. I am Bonnie (2014) is an award-winning documentary about the life of a football player, born and raised a woman (Bandana Paul), who was forced to leave the game and change multiple cities due to a different gender identity, and as a result of later undergoing Sex Reassignment Surgery to become, Bonnie. Bandana was one of the finest Indian strikers India had. However after the media splashed the news of Bandana’s different sexual identity, he was forced to seek exile and change professions from idol maker to taking up menial jobs and living a hand to mouth existence. The documentary sensitively portrays Bonnie’s breakdown as well as other vulnerable moments from his daily life without getting preachy. The film is directed by Farha Khatun, Satarupa Santra and Sourabh Kanti Dutta.

The second film under this category was - Abar Jodi Ichchha Karo ( If You Dare Desire, 2016), a feature film (fiction) that takes off from the ending of the filmmaker’s earlier documentary Ebang Bewarish ( And The Unclaimed,2013). It is a fictional work although it commences from a real life suicide committed by two girls in 2013 in Nandigram with one of them leaving behind a six page suicide note titled, My life.

“Songs of life” showcased two films. Naachi se Baachi (Dance for Survival, 2017) is a recounting of the life of the iconic Dr. Ram Dayal Munda covering the vast range of his personality and plethora of work. The film revolves around the theme of Dr. Munda’s culture apart from the deeply etched narrative by Gunjal Munda, Dr. Munda’s son, revisiting his father’s life and work. The viewers are taken on a trip to the Universities of Chicago and Minnesota where Dr. Munda went as a student, later became a teacher and finally returned with a wife leaving many friends and family in the foreign land but establishing permanent links with them. He later worked painstakingly building the cultural school of tribal languages, apart from being involved in formation of Jharkhand as a new separate state based on tribal identity. The film in a nuanced manner weaved social, economic and political movements along with documenting the life and times of Dr. Munda ending with him receiving the Padma Shri award in 2010. The film is directed by Meghnath and Biju Toppo who founded a NGO for Adivasis called Akhra.

Brief Life of Insects (2015) directed by Tarun Bhartia is one part out of a six part series around the birth of folk songs to live by in the Khasi hills of Meghalaya, sung by local farmers and workers. It opened for us a window into how music is very much a part of farmers’ lives and is not exclusive to music performers or folk singers.

A still from The Song of Margaret's Hope (2016). Pic: KPFF

The first session of day three titled “Working Lives” focussed on two different narratives of labour exploitations in two different parts of India through two documentaries. The first The Song of Margaret’s Hope (2016) revolves around the plight of tea garden workers in Darjeeling. The documentary shows the everyday abuse of the labourers in the closed tea gardens, where malnutrition and starvation deaths have become common. The continuous ceaseless exploitation rarely makes it to mainstream news headlines and such ‘news’ never reports much beyond death statistics.

The second titled Dollar City (2016), directed by RP Amudhan showcases the ground situation of garment and hosiery workers including migrant workers in the Tiruppur industrial hub. The film portrays how the state machinery, exporters, small and big entrepreneurs, commission agents, trade unionists and workers converge to prioritize export and to earn dollars by ignoring, marginalizing and eventually breaking the laws that protect the environment and workers’ rights.

The second session was called “Our Cities” with two documentaries fitting into this session. The first was Life Cycle (2016), directed by Malini Sur, an anthropologist who explores the place of the bicycle in the everyday lives of the city dwellers of Kolkata. The film takes us through the roadmap of how people from different walks of life – in particular the daily wage labourers and lower middle class commuters - are getting affected by the ban on cycles in several key streets of the city. It also highlights the role of some of the organisations trying to reclaim this space and commons, like the Cycle Samaj, Kolkata Cycle Arohi Committee, and Switch On which filed a PIL against the cycle ban.

The second film Mod (The Turn, 2016) is a beautiful attempt by Pushpa Rawat at communicating with young men who hang out at the notorious water tank in her neighbourhood in Pratap Vihar, Ghaziabad. The water tank or tanki is a space frequented by so-called no-gooders of the locality for playing cricket, cards or drinking and smoking up. The place does not allow access to women. The film interacts with these local boys and creates an engrossing dialogue exploring various issues in their daily lives, vulnerabilities, and relationships with friends and family in a dominantly male sphere. The film is a sensitive take on masculinity and precariousness of youth in small towns without the camera becoming voyeuristic or judgemental.

The third session, titled “Songs of Rebellion”, showcased yet two another finely crafted films. 18 Feet (2016) is about Karinthalakoottam, a popular folk music band of working class Dalit men performing in Kerala’s Thrissur district. The film follows the journey of the band from gaining huge popularity in the state to its trip to Malaysia for the Rain Forest Music festival and highlights their performance as a cultural asset. The musicians share powerful and moving personal stories and memories relating to untouchability that clearly ruled that Dalits were supposed to maintain an 18 feet distance from the upper castes to ensure the latters’ ‘purity’. In the film, music and life are inseparable as memories of caste-humiliation remain etched forever in the songs of rebellion.

Soz - A Ballad of Maladies (2016) is a powerful, evocative film on the poetry, music and art of Kashmir carrying the voices from Kashmir. Sufiyana music, hip hop, rock, words from wandering poets - the warp and the weft of the Kashmiri society, the effect of music and art on one’s consciousness - when words are not allowed, music become the vehicle of the soul’s longings, political aspirations and all expressions - a feeling innate in that very consciousness.

Day Four began with the heart-wrenching Even the Crows: A Divided Gujarat (2014), directed by British-Gujarati sisters Sheena and Sonum Sumaria. This film is in a state of ongoing conflict between memory and forgetting. It reminds the young and old in the audience of the sins and crimes committed by the Hindutva forces during the Gujarat riots of 2002 against the Muslim community. The then-chief minister Narendra Modi, who was accused of encouraging the riots, was able to evade justice and climb the ladder of power. The film documents the painstaking and ongoing struggle for justice for the survivors and kins of the deceased of the riots.

Sonam Singh’s short documentary Forbidden Notes (2016) chronicles the unjust incarceration of over four years and continued denial of justice to the young members of the Kabir Kala Manch, a troupe popular in Maharashtra. Kabir Kala Manch has been vocal with its compelling songs and skits against class and caste oppression, against the ruthlessness of capitalism and the marginalisation of the working class, Dalits, Adivasis and all oppressed people of our country.

Ekhono Ekattor (‘71 Still Now, 2016) directed by Manzare Hassin Murad chronicles the inception of the Shahbag movement, the build-up of the movement into one of the largest peoples’ movement in the world in recent years and the stories of the people behind it. Interestingly, Murad speaks to both people whose lives were directly affected in the liberation war of Bangladesh in 1971, for instance the family of Jahanara Imam, and those who have heard accounts of it from their parents. These people are a part of a huge upwelling of Bangladeshi nationalistic sentiment and anger against a foregone genocide and subsequent injustice done. “No more Razakars!” chants rent the air as activists demand the death penalty for Abdul Quader Mollah and other Jamaat-Shibir fanatics responsible for deaths of lakhs of innocents. The activists call for a ban of Jamaat parties. Posters and placards are made. Slogans are raised. The life sentence is replaced with the death penalty for Mollah.

A scene from movie A Walnut Tree (2015). Pic: KPFF

The closing film was A Walnut Tree (2015), directed by Ammar Aziz. It offers an insight into the lives of internally displaced people. An old man, living with his family in the Jalozai refugee camp speaks about his life back home, recalling a life that no longer exists. It is a life remembered through poetry and song evolving around a walnut tree that was planted by his father. He disappears one day. His son makes the journey back to his father's home, finding his way through the rubble, and sits on a collapsed wall, a part of the school his father taught in. Did the old gentleman make his way back? If he did, we wonder of the trauma he must have been through to see the life in his poems and memory completely destroyed. The walnut tree, so dear to his father, is almost symbolic of the often ignored trauma that internally displaced people go through for instance the people of Northern Waziristan.

This annual event of the Kolkata People’s Film Festival was planned as a set of events by PFC - without mega-sponsors and mega-stars - across the country. PFC has been small, funded solely by enthusiasts, and giving space to new filmmakers and their low-budget films.

Thanks to the changes in film technology, film-making has become more accessible, and not restricted to high-budget, Bollywood-style productions that are trapped in their ever-expanding dependence on market and capital. Over the past four years, the movement focussed on democratising the film experience at every level—a revolution made possible by low-cost digital technology has seen success without money at Kolkata.

Note: The article has been edited since last published to remove references between the Cinema of Resistance and Kolkata People's Film Festival (KPFF) in the last paragraph of the article as KPFF no longer has any relationship with Cinema of Resistance. KPFF believes referencing both organizations together in this article will be misinterpreted and carry a wrong message hence requested deletion of references.