The increasing privatisation of urban water supply in India has now reached small and medium towns, after repeated and mostly unsuccessful attempts in the metros and larger cities. The town of Khandwa in Madhya Pradesh became the first and highly publicised example of this when the process to privatise its water supply was initiated several years back.

As is usually the case with such schemes, the Khandwa project too began to be showcased even as it was still being rolled out, and even before it had started delivering water. Despite such attempts, however, it came under serious criticism as researchers exposed the various problems in it and citizens started protesting.

Now, the report of an independent committee set up by the Government of Madhya Pradesh and released in June 2013 has upheld most of the criticisms against the project and has called for annulment of the concession agreement signed with the private company. This will have far reaching implications as similar privatisation processes are being proposed or already underway for other small towns in the state.

The Khandwa Water Supply PPP Project

Khandwa is a small town in Madhya Pradesh, with an estimated population of 2.15 lakhs. It is located in the Narmada basin and is close to the massive Narmada Sagar dam project. The Khandwa Water Supply Augmentation Project was conceived of in 2006 and a 25-year-long concession agreement was signed in 2009 between the Khandwa Municipal Corporation (KMC) and the Hyderabad-based private concessionaire Vishwa Utilities Pvt. Ltd. Under the agreement, the company is to build and run this project as a Public Private Partnership (PPP).

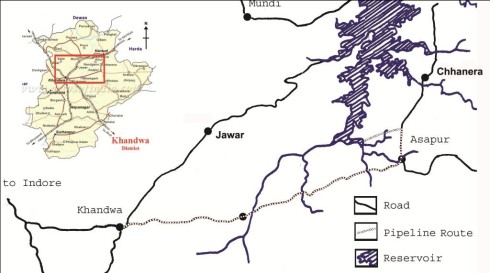

Map of project area.

The project involves bringing Narmada waters from the backwaters of the Narmada Sagar dam by constructing an intake on its tributary, the Chotti Tawa. The private concessionaire has to undertake construction of the intake well, water treatment plant, raw and treated bulk water pipelines, overhead tanks and the distribution system in the town, completing the construction phase within two years and providing operations and maintenance (O&M) over a 23-year phase.

The private concessionaire would supply 30 million litres per day (MLD) of water to the town's population at a base rate of Rs 11.95 per 1000 litres. The sanctioned project cost by the central government was Rs 106.72 crores, which has since inflated to Rs 115.32 crores.

Interestingly, while one rationale for involving the private sector in such projects is that they can bring in the resources that the Government sorely lacks, this project will receive 80 per cent of its outlay from the central government, 10 per cent from the state government with only the remaining 10 per cent being brought in by the private company. The latter now claims that this has increased by another 10 per cent as the cost of the project has gone up, but even then, its share remains small.

Indeed, this kind of arrangement is typical for such "private" projects. Most of these are executed under central and state government support as a part of schemes like Urban Infrastructure Development Scheme for Small and Medium Towns (UIDSSMT), where the total project cost is shared between the central, state governments and the local municipal body in the ratio of 80:10:10. In the case of Khandwa, the share of the municipal body is being provided by the private company.

However, it should also be noted that the International Finance Corporation (IFC), an arm of the World Bank that lends to the private sector for developmental purposes, is also providing a loan of $5 million (about Rs.27 crore) to Vishwa Infrastructure and Services Pvt. Ltd. and Vishwa Utilities Pvt. Ltd. for the private water supply and waste water treatment projects in Khandwa and Kolhapur.

Serious problems

Since the time the Khandwa project came under consideration and the tendering processes began, several local people, social groups and other organisations have been raising serious concerns, not only about the project itself but also about the way in which the whole privatisation process is being carried out. Local people had pointed out irregularities, lacunae, problems and long-term implications of the terms and conditions imposed by the privatisation agreement on the local people and their domestic water supply. This included repeated change in the scope of the project after tenders had been invited, non-transparent processes, and bypassing of even the elected city council while making major changes in the project.

Studies carried out by Manthan Adhyayan Kendra (with which the authors are associated) showed that that there are serious concerns about the conditionalities that have been imposed by the project on the local people. These include a high base water-tariff (to be increased every third year by 10 per cent), high additional costs associated with metering, road cutting, household pipe connections, a "no parallel competing facility clause" that disallows any water supply other than that supplied by the company, a tariff revision committee with no representation of local people, private control of water supply, long distance water transfer, high O&M costs and several others.

There is also no obligation on the private company under the contract to maintain service quality and performance; what is worse, residents face significant restrictions or prohibition on complaining against the company in case of poor service delivery.

More than 10,000 households filed objections against the project in a town where the total number of regular domestic water connections is a little more than 15,000. This showed the simmering resentment against the projects process, terms and conditions. (Pic: People protest against the notification of the scheme.)

Snowballing protests

Over the last few years, as awareness about the project spread, local voices of protest began to grow. Things took a new turn in March 2012, when some of the people and groups got together and began an intensive door-to-door campaign in the town against the project.

This was the time when the KMC was also trying to convince the people to accept its decision to privatise water supply by putting up hoardings and advertisements, claiming merits like no tariff hikes, good quality water and 24x7 supply for privatisation. But as the KMC began disclosing details about the conditionalities of the project which had thus far been kept under wraps from the local people as well as the municipal councillors, the anti-privatisation campaign gathered strength.

In December 2012, KMC published the notification "Water Metering and Regularisation Rules, 2012" regarding privatisation of water supply in the town, and invited objections and comments from citizens. The awareness campaign by local groups regarding the project and its impact bore fruit now and in an unprecedented development, more than 10,000 households filed objections against the project within a period of 30 days, in a town where the total number of regular domestic water connections is a little more than 15,000. This showed the simmering resentment against the project's process, terms and conditions that were completely biased against the people.

The huge number of objections against the project forced the Government of Madhya Pradesh to order the district administration to form an independent committee to look into these and resolve the problems. The district administration of Khandwa formed a seven-member independent committee on 3 March 2013 under the chairmanship of the Chief Executive Officer, Zila Panchayat, Khandwa.

The Independent Committee and its Findings

The committee had detailed interactions and discussion with the KMC, the private concessionaire, local groups and residents, and examined in detail all the representations, clarifications, information and documents placed on record.

During these detailed hearings and investigation, the independent committee categorised the objections into 51 categories which included concerns such as social obligations of KMC to deliver water services, unnecessary proposal of 24x7 water supply, no parallel competing facility clause, removal of public stand posts (public taps), no supply of non-revenue water, use of costly meters which the people would have to pay for, the handover of public assets to a private company for profits, high water tariffs, unilateral control of a private company in the tariff revision process and misleading parameters to show increased water requirements in the town.

Apart from these, questions had been raised regarding the selection of the project consultant and changes in the concession agreement and the construction material to benefit the private concessionaire. Local residents raised the issue of their right to water and stated that KMC cannot abdicate its responsibility to supply water to the people.

Several applications filed noted that the existing water supply to the town was sufficient and could be made more efficient only if problems in distribution were solved. The use of Narmada water supply was suggested only as an additional option.

The independent committee submitted its report to the state government on 1 June 2013. The report notes that changes in terms and conditions and specifications of the project have been made to benefit a specific private company. It goes on to state that there were serious irregularities committed by the KMC in the selection of the private consultant for the project and even in the tendering process. These included issuing tenders only locally and not at the national level, allowing very little time to fill the tenders, allowing changes to specifications after tenders had been called and modifications in the scope of the scheme.

Moreover, these changes were made in a completely unauthorised manner. For example, one change reduced the length of the distribution network from 120 kms in the original tender to 60 kms in Addendum 04. Such an addendum should have been necessarily approved by the general assembly of the KMC, which was not done. It needs to be mentioned here that almost 70 per cent of the project cost is on account of the bulk supply pipe material.

The report from the committee further notes that despite objections and repeated reminders on the issue of modifications in the specifications of pipes and construction material by the State Level Empowered Committee and the State Nodal Agency for UIDSSMT - Madhya Pradesh Vikas Pradhikaran Sangh . the municipal commissioner did not heed any advice and acted in the interests of the private concessionaire. Thus, according to the report, irregularities in the scheme have been committed at both administrative and political levels.

The report also brings out the inefficiencies of the private concessionaire and questions how a company, which has not been able to complete in four years the construction that it was contractually required to do in two, can be trusted to deliver an essential service such as water for the following 23 years. It also questions how and why the bid was filed by one company, namely Vishwa Infrastructure and Services Pvt. Ltd, while the agreement was signed with another entity, namely Vishwa Utilities Pvt. Ltd.

Having noted in detail various such irregularities and the serious manner in which the scheme was biased in favour of the private company and against the people, the report recommends that the concession agreement should be cancelled and the water supply services of the town should be handed over to a water board. It also rejects the proposal to transfer public water resources to the private concessionaire.

On the other hand, it recommends that there should be no parallel facility for water supply that would compete with municipal water supply. It also says that the number of public stand posts should be increased, supporting the right to water of the urban poor.

Implications

This report represents one more scathing indictment of privatisation of water in the country, this time from an official committee. It shows that the Khandwa story is hardly different from what has happened in water privatisation schemes in other parts of the country, with schemes being skewed towards the interests of private companies and against local people. The private companies bring in little in terms of resources, but gain control of water systems for long periods, enjoying huge profits with little accountability.

Even as the people of Khandwa wait to see what action the Government takes on the committee's report, it is important to note that its conclusions have

implications that go beyond Khandwa. This report should wake the government up to the serious issues implicit in privatising water supply. It should lead the

authorities to abandon such schemes, and instead, enshrine the basic right to water as a fundamental right, accepting the essential obligation of the state to

provide water. This should be combined with steps to operationalize accountability and performance in public water systems.