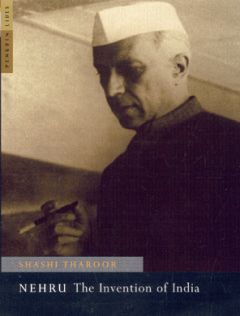

Of all the public figures in India, Gandhi and Nehru are the ones subjected to the closest scrutiny. During their life-times both were towering personalities with a decisive influence on the events of the day. While Gandhi's moral philosophy and practice had a tremendous impact on India's struggle for Freedom, Nehru had a greater impact on the modern Indian identity. In recent times their influence has waned, but there has been no dearth of biographical interpretations like Shashi Tharoor's brief exploration of the life and career of Jawaharlal Nehru who's "impact on India is too great not to be re-examined periodically".

Tharoor finds that Nehru's imprint on India rests on four tenets, namely "democratic institution-building, staunch pan-Indian secularism, socialist economics at home, and a foreign policy of non-alignment". Understandably, therefore, apart from a recapitulation of Nehru's eventful life the volume also offers a contemporary assessment of the merits and pitfalls of these fundamental features.

The person

For four eventful decades of India's modern history, Jawaharlal Nehru was a dominant political figure. Drawing on a reading of existing literature, Tharoor offers a breezy narrative that encapsulates Nehru's personal life and public engagement in India. Given the constraints of a brief biography, the book succeeds well enough but the insufficent detail in such a short narrative introduces a certain degree of superficiality. This limitation becomes particularly evident in the retelling of the seventeen years of Nehru's premiership where events are subjected to severe compression that often strips them of their wider significance.

![]() Jawaharlal was born on November 14, 1889 to Motilal Nehru, a wealthy,

successful Kashmiri lawyer of Allahabad. In later years, the Nehru clan

distinguished itself by relinquishing its wealth and comfortable social

position to throw its lot with the Freedom Struggle. While their personal

privations were not as acute as those of millions of poor Indians,

Jawaharlal's identification with the masses is not without significance.

His rapid ascent to the status of a national leader is somewhat of an

unexplained phenomenon, but this volume does not shed much light beyond

pointing to the obvious influences including Gandhi's grooming of the

younger Nehru. Educated at Harrow and Cambridge in England, Nehru's early

years betrayed nothing of the great responsibility and adulation that

would be heaped on him. Greatly admired by the vast Indian populace, Nehru

was viewed as a major threat by the British who made him His Majesty's

unwelcome guest - an astonishing total of 3262 days in seven different

jails. Some nine years of incarceration, an indifferent marriage cruelly

cut short by his wife's death just when love and understanding was

developing, and the anxiety of taking care of his family under trying

circumstances - all of this would have crushed the spirit of any ordinary

person. But Jawaharlal weathered the storm within and the many crises

without to emerge as the leader of a free nation.

Jawaharlal was born on November 14, 1889 to Motilal Nehru, a wealthy,

successful Kashmiri lawyer of Allahabad. In later years, the Nehru clan

distinguished itself by relinquishing its wealth and comfortable social

position to throw its lot with the Freedom Struggle. While their personal

privations were not as acute as those of millions of poor Indians,

Jawaharlal's identification with the masses is not without significance.

His rapid ascent to the status of a national leader is somewhat of an

unexplained phenomenon, but this volume does not shed much light beyond

pointing to the obvious influences including Gandhi's grooming of the

younger Nehru. Educated at Harrow and Cambridge in England, Nehru's early

years betrayed nothing of the great responsibility and adulation that

would be heaped on him. Greatly admired by the vast Indian populace, Nehru

was viewed as a major threat by the British who made him His Majesty's

unwelcome guest - an astonishing total of 3262 days in seven different

jails. Some nine years of incarceration, an indifferent marriage cruelly

cut short by his wife's death just when love and understanding was

developing, and the anxiety of taking care of his family under trying

circumstances - all of this would have crushed the spirit of any ordinary

person. But Jawaharlal weathered the storm within and the many crises

without to emerge as the leader of a free nation.

In 1947, Nehru's inheritance as Prime Minister included the barbaric legacy of Partition, the assassination of the Mahatma, and a large, unwieldly nation with profound problems and an uncertain future. Although Premiership was perhaps a crown of thorns, it was also an exciting time with the promise of a brighter future. But within a decade, Nehru was at the peak of his national influence and international eminence. From that pinnacle of acclaim, as Tharoor points out "there was nowhere left to go but down". The Chinese debacle which followed in 1962 was a shattering blow from which Nehru never recovered. A long, luminous career ended with his death on May 27, 1964. His reputation tarnished, Nehru was no longer the demi-god he had been at the unchallenged heights of his career.

Nehru's personality has often come under a lot of scrutiny. He was known to be utterly loyal to friends but also a poor judge of character. In his early years, Nehru was also quite other-worldly and did not pull his weight in providing for his family, a burden the elderly Motilal took on himself. While their relationship is well portrayed, Tharoor infuses too much of a sense of certitude in Nehru's views on a variety of subjects, international affairs and socialism in particular. In contrast Nehru's Autobiography clearly demonstrates a certain degree of confusion in his mind. Jawaharlal it seemed always made up his mind firmly, only to be persuaded to change his view or hold his brief. While such a spirit of accomodation is also displayed by a leader like Gandhi, in Nehru's case this was to become a liability. The fine art of leadership demands a subtle balance between accomodation on specifics and refusal to compromise on principles. But often when matters came to a head, for instance the Congress Socialist Party's challenge to the conservative elements within or the crisis arising out of Subhas Bose's election, Nehru allowed himself to be persuaded against his wishes.

A major factor in Nehru's prevarication was his deep and abiding relationship with Gandhi. While the two differed on fundamental principles like the nature and meaning of non-violence in politics and the future economy of independent India, their mutual affection prevailed. Tharoor does well to portray the paradoxes of this relationship, but he falls prey to the familar approach of debunking the radical nature of Gandhi's life and thought by portraying it either as opportunistic or quixotic with no internal logic. Thus Gandhi's organisation of an ambulance brigade during the Boer War in South Africa is portrayed as an attempt to "curry ... favour". While Gandhi's philosophy - and its practice - was truly radical, for Tharoor "his baffling fasts and prayers and penchant for enemas, stood for the spirit of an older tradition that imperialism could not suppress". Here the writer, perhaps unwittingly, follows in the odious tradition of Ved Mehta where private, scatalogical issues are conflated with 'baffling' public fasts.

The four pillars

To turn to the first of the influences that Tharoor identifies, it is well known that Nehru was a practitioner par excellence of the democratic idiom. With an incredible and unflagging energy he travelled the length and breadth of the country and probably met more Indians than any other leader save Gandhi. As Prime Minister he was eminently successful in establishing sound traditions of parliamentary debate, which has sadly declined to a disgusting spectacle today. Nehru was an active participant in the most exciting political experiment in the world, namely universal adult franchise in India. Unlike the European experience, the right to vote arrived in an India where stupendous economic inequalities and a deeply feudal tradition meant that the health of our democracy was by no means assured. The years after Independence were indeed 'dangerous decades' and political scientists continue to grapple with the unique trajectory of the Indian democratic experiment. While not romanticising or ignoring the depths of our current problems, it's worth noting that "through the strength of his personality Jawaharlal held the country together and nurtured its democracy". Although parochial identities of caste and religion have since reasserted themselves on the Indian political scene, the Balkanisation of India no longer appears a significant possibility. For this we are grateful to the likes of Nehru and Patel.

While Nehru was a fine practitioner of democracy his record is by no means unchallenged. Whether Nehru groomed Indira for high office is a complicated question that is often raised. The evidence seems to suggest that Nehru did not groom her in any overt manner. Nevertheless, Nehru's image is unfortunately sullied by the curious case of the daughter's sins visiting the father. However, in his eagerness to mount a defence, Tharoor makes an astonishing assertion regarding Indira Gandhi and the repeal of the Emergency. Incredibly he claims that "it is a measure of the values she imbibed at her father's knee that she then held a free and fair election and lost it comprehensively". Why these lessons in democracy failed to be an impediment against the imposition of the Emergency in the first place remains unanswered.

While Indira's rise to power and autocracy occured after Nehru's death, his inability to accomodate fellow nationalists within the post-Independence Congress was a tremendous failure. With the early demise of Patel and no towering Gandhi around, Nehru was the banyan tree under which nothing grew. His Congress found space for quite a few unsavoury characters but stellar figures like the incorruptible Socialist Jayaprakash Narayan, Rajaji and Acharya Kripalani had to make an exit. Curiously, Tharoor turns this argument around and asserts that "Jawaharlal's efforts to resist the right-wing tendencies within his party and government were not aided by the continuing departures of his socialist allies".

This failure is particularly troubling given Nehru's life-long affinity with progressive tendencies within the Congress. His criticism of the conservative elements of the Congress and of Gandhi's economic vision was premised on a socialism that would deliver where all other forms of political and economic organisation would fail. Nehru's close reading of Indian history with a Marxian lens had led him to a sharp understanding of the nature of class in India. But Tharoor is entirely oblivious to the centrality of the class question in understanding the forces that operated in Nehru's Congress. But others including the polymathic historian D. D. Kosambi clearly recognised the primary influence of the class factor. Kosambi's review of Nehru's Discovery of India was titled "The Bourgeoisie Comes of Age in India", a characterisation that Nehru himself would have agreed with if the self-analysis in his Autobiography is any indication.

The young Nehru was quite vociferous in his criticism of the conservative old-guard in the Congress and even his mentor, Gandhi, was not spared. His own introduction to popular politics was through the vexed problems of UP's farmers and Tharoor claims that "the Congress of Jawaharlal Nehru was committed to land reform" whereas "the League was in thrall to big Muslim landowners". But with the arrival of Independence the earlier urgency seems to have evaporated and land reform was still-born in most of India. Nehru himself referred to the need for many 'New Deals' in India in his Autobiography written in the early 1930's. But astonishingly little was done on the matter and the overwhelming energies were focussed on the mechanisms of planning the economy. While a handful of die-hard idealists like the Gandhian economist J. C. Kumarappa continued to challenge the direction the Congress took under Nehru's stewardship, very few commentators seemed to be troubled by Nehru's emphasis on heavy industries and neglect of the agrarian economy.

Although Nehru prevaricated on these issues, his commitment to maintaining the secular credentials of the Indian state was impeccable. Jawaharlal was not a practising Hindu, but he had a deep affinity for India's culture, the richness of which he 'discovered' for himself and countless readers since. The agony of Partition and the vulgar politics of the Muslim League were a direct challenge to the secular identity of India. With Gandhi falling victim to another communal vision, it was left to Nehru to become the most visible exponent of secular practice in India.

Nehru's approach to secularism has come under severe assault in recent times from both cultural critics who see it as being too much of a Western import ill-suited to India's needs and from vicious and unprincipled communalists from the Hindutva brigade. While communal politics had taken centre-stage in recent times and despite the killing of Muslims in Gujarat a few years ago, India has retained a tenuous faith that "the future that animated Nehru's vision of India seems so much more valuable than the atavistic assertion of pride in the past that stirs pettier nationalists". While the charge against Nehru's Westernised perspective on religion carries merit, the choice is obvious if one is offered only his brand of secularism and the shrivelled, communal vision of a home-grown bigot.

While Nehru's approach to religion was defined by his exposure to highly syncretic traditions, his own brand of internationalism was shaped by both the bitter Indian experience of imperialism and a burning desire to see the colonies freed of their bondage. Unlike his colleagues in the Congress, Nehru was intimately familiar with European and, in turn, world issues. This familiarity had a profound influence, in determining the Congress's view on international affairs before Freedom and the policy of non-alignment after Independence. Strangely for a career bureaucrat with the United Nations, Tharoor has no sympathy for the lonely furrow of non-alignment that Nehru was ploughing for India. While he does not explicitly state it, Tharoor seems to be of the opinion that Nehru seriously erred in adopting a moral position of neutrality during the Cold War. Tharoor is more comfortable with the idea of moulding national perspectives on the basis of their instrumental value on the international scene. In contrast, Nehru sought to press home the point that international relations and diplomacy ought to be governed by a sense of universal justice and by the objective reality. Like many recent commentators, Tharoor seems to imply that by not openly aligning India with American interests, Nehru had denied us the opportunities it would have offered us.

Paradoxically, writers like Tharoor expect our leaders of the Freedom Movement to have fought the British on a moral plane but thereafter turn chameleon and deal with the down-and-dirty realpolitik of international bargaining in the name of protecting national interest. The strength of a moral position, it is suggested, has no use in the messy world of international diplomacy where economic and military strength is the only currency. But this is a direct repudiation of the Freedom Movement that was not based on an arms struggle but on a direct moral challenge to the Empire. While some cannot imagine a different basis for relationships between nations other than self-interest, visionaries like Nehru were not afraid to dream of a world based on a more edifying premise of shared humanity and a quest for justice.

Tharoor's greatest ire is aimed at Nehru's approach to economics. For him "Nehruvian socialism was a curious amalgam of idealism, a passionate if somewhat romanticized concern for the struggling masses, a Gandhian faith in self-reliance, a corollary distrust of Western capital and a 'modern' belief in 'scientific' methods like Planning". However, the reading of distrust of Western capital as a mere corollary to a belief in self-reliance is not rooted in historical fact. Self-reliance was not simple-minded Gandhian faith but a creed that an entire generation of freedom fighters lived by. While Gandhi and Nehru profoundly differed on the direction of India's economic agenda and its priorities, their aspirations for the nation were entirely rooted in the belief that an India battered and bruised by two centuries of economic pillage should lift itself up by its bootstraps. But Tharoor believes that by shutting out foreign investment, Nehru set the clock back on India's technological surge ahead.

This perception enfolds two errors. Firstly, the glib assumption that Western capital was easily available to India is wrong. The only real option that was available to India was to subjugate its own interests and self-respect and remain within the West's 'sphere of influence'. The example of steel plants is a case in point. While the West refused to provide India with the requisite technology, the conditionalities quickly changed once the Soviet Union stepped in with its offer of a plant. Similarly the financial and food aid packages provided to India were only grudgingly offered by America after its Ambassador, Chester Bowles, had used the bogey of Communism ruling the roost in India to get around reluctant senators who were unhappy with India's neutrality.

Tharoor reflexively claims that Indian business and entrepreneurship was severely thwarted by the lack of foreign capital investment. This smacks of reading the situation of the past with a contemporary ideological perspective. While counter-factual arguments on economic history are always tendentious, there is ample evidence to show that let alone suffering under the stifling restrictions imposed by an overwhelming state bureaucracy, Indian business had in the initial years actively sought such state control of markets to keep out external competition from affecting their profits. The current clamour to open up to international business is located in a changed international economic regime where the technological factors that operate are entirely different from those in the fifties and sixties. One could conjecture that without the electronic communications revolution in the eighties, Indian business would not have found the new opportunities that it so vigorously defends today.

Secondly, like many of today's commentators, Tharoor is obsessed with foreign investment as if it were a panacea to India's myriad economic and social problems. This is wishful thinking at best. A decade and a half of opening up Indian markets to foreign investment and trade is not a story of unmitigated success. In fact the social and economic paradoxes that existed in the Nehruvian era have now deepened even further. While a section of India's urban elite benefits from tremendous profits, Indians by and large are worse off than a decade ago. Nehru's watered-down brand of socialism did not succeed in its stated objective, but at the very least it nurtured hopes of levelling our great social inequalities.

In contrast, foreign investment in a handful of sectors in collaboration with a small Indian elite does precious little for the larger Indian economy. Today India is witness to the curious phenomenon of jobless growth, the failure of trickle-down economics and a debilitating collapse of the rural economy from which the only escape for thousands is suicide. Despite the claims of benefits that accrue from integration into the global economic order, the evidence in India seems to suggest a very different story. While some have accumulated huge fortunes, in Utsa Patnaik's depressing description, India is now a 'republic of hunger'.

The idea of an 'invention of India' is a strange and persistent one. The exigencies of Empire meant that the British had to consistently claim that India did not exist before they arrived, thus justifying their presence which was increasingly challenged. Curiously Tharoor seems to accept this colonial premise and goes on to claim that "it was Churchill's view of India that would one day make Jawaharlal Nehru's 'invention of India' necessary". However there is no further development of this argument, which is strange given the significance one accords to the title of a book. In the absence of arguments by the author on this fundamental premise of the book we can only address the broader perceptions attached to such a premise.

While politically disparate, Indian culture has historically been marked by temporal and geographic continuity. Also, while political India as we know it today was consolidated by the British for administrative purposes, the fact remains that it is during this colonial period that most modern Western nation-states themselves emerged. By insisting that India needed to be invented, the imputation was that in the two centuries prior to 1947, India would have remained essentially unchanged but for the presence of the British. While there is no saying what forms of political organisation might have arisen if India's conquest had not occured, this by itself does not validate the assumption that the current political organisation is the uniquely natural and definitive form.

In reviewing a book that is itself short, it is not possible to do justice to the many dimensions of Nehru's persona and influence. As a person central to India's public life for decades, Nehru is naturally a complex figure and the meaning and value of his legacy must be vigorously contested and debated. Given Nehru's long career at the helm of independent India the choices he made necessarily had serious consequences for India's future. While Tharoor criticises Nehru for his shortcomings, he also recognises the immense value of Nehru's contribution to India. Thus while he has some reservations he refrains from Nehru-bashing, a political sport favoured by many across the entire spectrum of Indian opinion today. Nehru had his contradictions and weaknesses, but he also had a passionate love for his land and his people, a willingness to sacrifice everything for an ennobling cause, and above all an uncompromising integrity. All of these traits have been largely absent in Indian public life of the past three decades. While his legacy was a mixed one, a much larger part of the blame for our current problems rests with those who have had a role in determining India's fate since Nehru's demise way back in 1964. The failure to make something worthwhile of an Indian life is ours, not Nehru's.