Masooma Begum had her first child at 16. That was in early 2012. Even today, the horror of that experience is clearly etched in her mind. Emotionally vulnerable and physically weak, this resident of Mahesmara village in Jahangirpur Gram Panchayat (GP) was forced to have a painful and complicated delivery at home.

Mahesmara is situated in one of Bihar’s most backward districts, Kishanganj “There is a government health centre at Damalbari, three kilometres from our village, but it has never been functional. So, we have to go to the one at the block level in Pothia, which is 25 kilometres away. Hiring a vehicle costs at least Rs 800 to Rs 1,000. My husband simply could not afford it. I had an unassisted delivery at home and somehow my daughter and I survived,” recalls the young mother.

Masooma is 18 now and expecting her second baby. But she is not panicking this time because not only is she better informed and prepared, even the state of healthcare in her area has improved. “I am aware that I can avail of the free ambulance service to the Primary Health Centre (PHC). I also know that after delivery I will get Rs 1,400 under the Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY). These days, I make sure that I get my weight and blood pressure checked periodically and I am no longer anaemic because I have been regularly taking the iron pills,” she informs with a bright smile.

This transformation in Masooma – as well as hundreds of other women in Jahangirpur GP, Pothia block – has been brought about under the Department of International Development (DFID)-supported Global Poverty Action Fund initiative, ‘Improving Maternal Health Status in Six States in India’, launched by Oxfam India in October 2012. Across Bihar, the intervention has reached out to women in 70 villages of three districts, Kishanganj, Supaul and Sitamarhi.

Corruption in the maternal health sector

When the Bihar Voluntary Health Association (BVHA), Oxfam’s grassroots partner, started work in the 22 project villages of Kishanganj, the first thing that came to light was that the benefits were being misappropriated and not reaching the new mothers.

“During the discussions held with the community someone pointed out that a woman in the neighbouring village had collected the cash incentive given under JSY twice within nine months. Subsequently, it turned out that several women in Mahesmara had, in fact, received nothing. With the help of BVHA volunteers, we questioned our Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) and followed it up at the panchayat level as well. What came out from the inquiry was quite shocking – cash had been paid out against all the names registered for institutional delivery although none of the actual beneficiaries had got it,” shares Noorbano Begum, 46, President of the Mahesmara Village Health, Sanitation and Nutrition Committee (VHSNC) set up by BVHA under the guidance of Oxfam India.

Such committees, comprising 15-20 members, including eight to nine women, are present in all the project villages. Unlike the Village Health and Sanitation Committees (VHSCs) that are constituted by the government at the panchayat level, the VHSNCs operate at the village level. Incidentally, Noorbano is also a member of the VHSC in Jahangirpur GP, which comprises three villages.

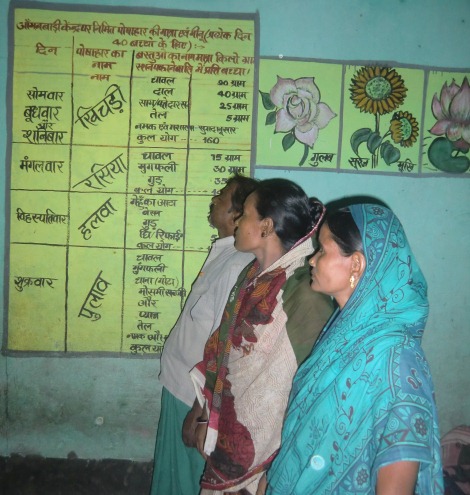

Members of the Village Health, Sanitation and Nutrition Committee (VHSNC) of Mahesmara examine the diet chart specially created for children at the local anganwadi centre. Pic: Ajitha Menon\WFS

While auditing the functioning of the scheme, another startling discovery was made: money had been issued in the name of local women who had gone to neighbouring West Bengal for their delivery.

“There is a big hospital in Islampur, West Bengal, which is 10 kilometres away. Many couples go there for delivery even if they are registered with the local Auxiliary Nurse Midwife (ANM). Besides, many women married here have maternal homes in Bengal and go there for delivery. We realised that the money had been withdrawn on the basis of registration but was never paid,” elaborates Mustaq Alam, 48, another VHSNC and VHSC member.

Fighting irregularities

The people of Mahesmara decided to fight the corruption. Its VHSNC members wrote to the Pradhan of Jahangirpur GP, the district Medical Officer in Charge (MOIC), the Civil Surgeon and the District Magistrate regarding the anomalies in the disbursement of JSY funds. Community tracking finally revealed money laundering to the tune of Rs 30 lakhs in Pothia block.

“We became aware of the power we have when we could manage to collect evidence and put it before the authorities who were compelled to suspend and later arrest the MOIC and others involved. At the same time, thanks to the movement, under which rigorous advocacy was done by BVHA, every woman in Mahesmara, and those in the nearby villages, too, got to know of their entitlements under JSY,” says Noorbano.

In the last two years, there has been a marked improvement in pregnant women’s access to facilities such as free ambulance service, cash incentive and check-ups done at the anganwadi centres. The VHSNC members, however, are not resting on their laurels, as there is still a lot that needs to be done.

“Though my name had been registered with the ANM, I delivered at the Lion’s Club Medical College, a private facility in the area (accredited under JSY). I have a proper birth certificate issued by them as well. But the PHC has refused to give me the cash incentive and even the gram panchayat is not giving me a birth card. In fact, the panchayat sevak has even asked for Rs 600 to issue it. Now the VHSNC is handling the case and I am confident that there will be a solution soon,” says Afroza Begum, 24.

“There are nine such cases in our village and the community is creating pressure on panchayat officials for a resolution,” points out Md Habib Alam, Afroza’s husband.

Here’s why there is a need to ensure smooth implementation of JSY in the region. Kishanganj has a low literacy rate of 57.04, with female literacy at a low 47.98. Among the Muslim community, the female literacy rate is still lower and most girls are married before 18. This has an impact on the infant mortality rate here which is 56, while the maternal mortality ratio is as high as 349 (Annual Health Survey 2012-13).

“Deliveries at home are a risk for the mother and children. Yet, the reality is that most people don’t spend money to reach the PHC or hospital… Currently, there is just one ambulance to ferry women so it’s not always at hand,” reveals Nazli Begum, 35, ASHA worker of Mahesmara, adding, “Despite the challenges, over the last two years, institutional deliveries have increased from 20 to 60 per cent.”

Meraj Danish, BVHA’s Thematic Coordinator in Kishanganj, is positive about the progress: “We have succeeded in sensitising the community towards the issue of maternal health. The ICDS meals for infants, pregnant women and lactating mothers are being monitored by the community, as is the distribution of iron tablets. Pregnant women are following the diet chart and getting their weight and blood pressure checked timely. Soon we will step up advocacy related to conducting protein urine test and other blood tests, which are covered in JSY, but are not being done anywhere in the state as yet.”

Apart from these activities, the VHSNC has been keeping an eye on the utilisation of the untied funds given to every village in the panchayat. “We have liaised with our ANM, Rebecca Tudu, to use this money to build concrete platforms around tubewells, make proper drains, toilets, and so on. This has proved be a boon for expectant mothers,” says Noorbano.

The progress in improving maternal health parameters at the grassroots has been slow but steady. While the community has moved forward and decided to protect the interests of pregnant women and newborns, more work needs to be done to ensure better service delivery.

© Women’s Feature Service