The Craft Bazaar, housed in a huge tent on the vast grounds of PG College in Secunderabad's bustling neighbourhood of Paradise Circle, has various craftspeople visiting from all over the country to showcase their merchandise. Prominent among them are artisans from Orissa, Bengal, Kashmir, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Delhi and Uttar Pradesh. K. Mallick - who has come here from Calcutta - stands vigilant in his stall showcasing beautiful handicrafts made out of jute and terracota. He is not very happy with the arrangements made for the Crafts Bazaar, he vents his frustrations, "In these days of plastics, people do not appreciate handicrafts. Look where they have placed us, next to a circus!"

Not far away, at the Great Bombay Circus skimpily dressed nubile Russian acrobats and Indian trapeze artists steal the show from its drab neighbour. It's tough competition for the artisans at the Crafts Bazaar.

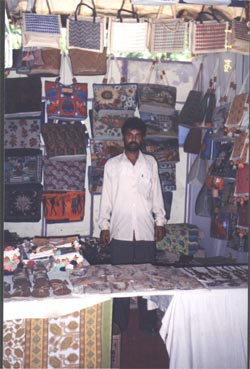

![]() The state government's handicrafts department arranged the bazaar. The artisan's problems do not stop with the poor choice of location, but also on practicalities like renting stalls, their placements, transparency, etc. Mallick clarifies, "Out here nothing is transparent, each stall owner is paying a different rent. Some give Rs.10,000 a day, some Rs 15,000, a few even pay Rs 20,000. It depends on who manages to get their rents lowered, or on the prime place they acquire. Corner stalls, front line stalls are in great demand and exhibitors are keen to buy them. There is no unity among all of us craftspeople. Here we all can unite and ask one single rent for all the stalls, but no, we all try to fish for ourselves and in the process muck up the whole thing for others."

The state government's handicrafts department arranged the bazaar. The artisan's problems do not stop with the poor choice of location, but also on practicalities like renting stalls, their placements, transparency, etc. Mallick clarifies, "Out here nothing is transparent, each stall owner is paying a different rent. Some give Rs.10,000 a day, some Rs 15,000, a few even pay Rs 20,000. It depends on who manages to get their rents lowered, or on the prime place they acquire. Corner stalls, front line stalls are in great demand and exhibitors are keen to buy them. There is no unity among all of us craftspeople. Here we all can unite and ask one single rent for all the stalls, but no, we all try to fish for ourselves and in the process muck up the whole thing for others."

Mallick has another woe to add, "With the circus next to us most come to pass their time, some who buy haggle terribly. They neither value the product nor the work we put in. To them there is no difference between a plastic bead necklace and a terracotta bead necklace." Bargainers constantly badger all the artisans. Away from the circus tents, the hassled officials and the upset exhibitors, in a tiny by-lane of the old city's famed Charminar, Ateequnissa is busy working at her sewing machine. She comments, "Earlier we used to feel bad when people bargained, but it's the market now, our work is to sell. If s/he does not buy, someone else will. Who does not respect art haggles, whoever reveres art buys respectfully."

The wry complaints are true enough, but they also are not the whole story. Behind the obvious irritation with things that are going right at the bazaar is a story of much that is turning out well. Ateequinssa is not the usual sort of handicraft worker who is vulnerable to all sorts of exploitation. Instead, she is a leader of 35 women members teaching them patchwork and coconut shell button making. And she is very proud of her association with Mahila Sanatkar, the organization she joined in 1994.

Amidst the crowded by-lanes of the Charminar Bus Stand area, stands Mahila Sanatkar's cream colour building. This organisation is a part of COVA's (Confederation of Voluntary Organisations) women's socio-economic empowerment programme. In the early 1990s, the old city saw a number of communal riots and COVA was formed to promote communal harmony. As Asiya Khatoon, director of Mahila Sanatkar says, "After the riots we surveyed many areas and found that the most affected are the women. When we went there for relief work, we were told that instead of doing relief work we should do something that will not create problems (kuch aisa kariya jisse fasad he naho). So we created a platform to empower women economically."

In 1994 seven units were established in the old city. Women then learned basic tailoring. Soon they were formed into groups and their learning and progress was monitored closely, with constant interactions and regular meetings. Asiya Khatoon adds, "We realized that the knowledge levels were poor. We started upgrading their skill level by taking them on exposure visits, gave them training and made them aware of more aesthetic designs. For example we took 18 members for 22 days to Ahmedabad, Delhi, Lucknow, Calcutta and showed them the work done by SEWA, Muzaffar Ali, the Bengal Women's Association, etc. and when we returned their mindset had changed. They urged us to let them experiment their creativity and we did. Later loans were taken from COVA and exhibitions were set up which showcased their talent. Now we have 21 production units where basic course in tailoring is taught but each center specializes in a specific item, say embroidery, quilting, beadwork, patchwork, zardozi. We now have 65 members and around 600 associate members."

Mahila Sanatkar hires designers but does not believe in establishing any kind of franchise with them. "The designers put their own label and sell. We have our own identity and brand name MAHAC. When we do so much work and put in so much skill which our people possess why should they not get the credit?" Asiya understands the mechanism well, and bewares the name game. "If they don't give us credit then we do not associate with them. Franchises are not good in my view because there is a lot of exploitation and these designers earn a lot. We understand this very well. They rake in 200 per cent profit. For example the jute bag, which we sell for Rs. 85 will be sold for Rs. 250 in their show room. In Lucknow the state of artisans is very bad. They get paid very little despite their skill at handicraft. I saw a dupatta which was beautifully crafted all over and the worker had worked three days over it and been paid Rs.30 as a lump sum. The same thing I saw at the Bhaskara Palace exhibition was for Rs. 900!"

Ateequnissa says, "Mahila Sanatkar has become independent after quite sometime but we still do not have the capacity to go out on our own to do market surveys or exposure visits. It is not easy to recycle money into markets. There is a lot of competition alongside the exploitation. In Mahila Sanatkar we have sorted out the problem of giving credit to each center by allotting one specific task to one center, say my center will make only coconut shell buttons and no other center will make it. This is how we have developed our identity."

• Burqa-clad and empowered

There is a quiet determination to such work that isn't obvious in the crowded bazaar, where the struggle for survival and economic security seems to be the only noticeable thing, and artisans have many tales of woe to tell. But these are not stories of despair. Instead, they are the ordinary grouses of traders everywhere.