It was films last year; it is writings this year. Avahan the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundations India AIDS Initiative is bringing together the best of popular culture to mainstream AIDS issues.

AIDS Sutra, an anthology, has 16 award-winning authors write about the epidemic in India and how communities across the country are grappling with it. Salman Rushdie writes about Mumbais hijras, William Dalrymple about Belgaums devdasis, journalists Aman Sethi and Sonia Faleiro give us a glimpse of lives of truck drivers and sex workers and Vikram Seth and Siddharth Dhanwant Shangvi put the spotlight on the other end of the spectrum - HIV among the affluent and the privileged.

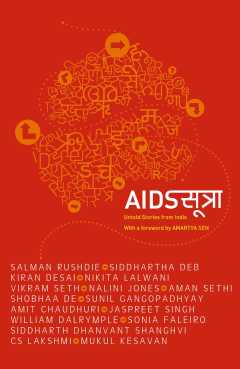

![]() AIDS Sutra: Untold Stories from India. Edited by Negar Akhavi. Random House India, Rs 395

Produced in collaboration with Avahan India AIDS Initiative, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

AIDS Sutra: Untold Stories from India. Edited by Negar Akhavi. Random House India, Rs 395

Produced in collaboration with Avahan India AIDS Initiative, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

All the writers are Indian, except Dalrymple; at least nine belong to more than one continent. Only appropriate then that they come together to write about what Bill Gates has termed the most important story of our times.

Avahan the Gates Foundations India AIDS Initiative works in Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamilnadu, Manipur and Nagaland. It was established in 2003 and aims to expand access to HIV prevention among at risk populations such as sex workers, injecting drug users, men who have sex with men, transgenders and truck drivers.

Last year, Avahan funded filmmaker Mira Nairs AIDS Jaago project in which well-known Indian filmmakers Vishal Bhardwaj, Santosh Sivan, Farhan Akhtar and Nair herself made short films on AIDS. The films, starring actors like Shabana Azmi, Boman Irani and Prabu Deva, dealt with issues like an HIV-positive child facing stigma in school or a middle-class family dealing with the fathers HIV infection.

The films were aired on NDTV last World AIDS Day (1 December). This year, AIDS Sutra has brought together a galaxy of some of the best-known writers. Essays from the book have been published as extracts in leading mainstream newspapers across the world to mark the books launch this August.

Clearly, the idea is to go mainstream. Negar Akhavi, editor of AIDS Sutra and programme officer with Avahan until recently, says, There is a magic to arts and literature. I think by its very nature people approach it with their guard down and for that reason it can be transformative. We have all read a novel or watched a film that provoked a sense of empathy toward a character or a situation we may have otherwise dismissed. Hopefully, this collection of essays will provide a similar opportunity.

•

Surviving a battle fought every day

•

Secret status, risky schooling

Mumbai-based journalist Sonia Faleiro tells the story of the unspeakable violence women (and men) sex workers face at the hands of policemen day after day. She tells the brutality and bestiality as is. Faleiro says the police carry their social conditioning about sex work when they are on duty and what makes this dangerous is that they have the power to act on their bias. When the sex worker gets beaten up, whom does she go to in order to file a complaint?

The stories are about the relationship between the powerful and the powerless in our society the citizens and the non-citizens. Bengali writer Sunil Gangopadhyay explores the winds of change in Sonagachi over the last 50 years. Kolkatas infamous redlight area and perhaps South Asias largest is on the world map as a best practice in AIDS response. Sonagachi of the sixties has not changed much on the outside, Gangopadhyay says the dim and airless rooms, filthy toilets and yet, the women with crushed and defeated faces now wear a new look. The psyche of women is different today. They dont perceive themselves as sinners and fallen women anymore. He notices how the women speak of their profession quite naturally and spontaneously as though it was one of many. Exploitation has reduced, women now have a cooperative bank, there is a self-regulatory board to prevent entry of minors, and children of sex workers have shrugged off the stigma they carried for centuries.

The stories deal with the socio-cultural dynamics of the times we live in. Falerio talks of the failing system--policemen demand bribes, corruption is rampant. But look at what policemen earn as their monthly salary, she reminds us--about the same as a maid. In coastal Andhra Pradesh, women who have been traditional sex workers for generations tell Kiran Desai, In earlier days they would put a betel leaf in the girls hand to indicate a future assignment, now they exchange cell phone numbers.

![]() Salman Rushdie with Laxmi. Pic: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation/Prashant Panjiar 2008.

Salman Rushdie with Laxmi. Pic: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation/Prashant Panjiar 2008.

Gangopadhyay recounts a story one hears commonly among sex workers in West Bengal: a labourer - a lower-caste woman finds rampant abuse at the worksite so drifts into sex work reasoning if this must be the way it is, she may as well earn to meet her familys needs. Clearly, the lines are merging. Its not just the sex worker in the brothel who is at risk; countless others are being sexually abused, coerced into sex work, and given this power equation, entirely powerless to protect themselves from HIV.

The third gender of India still needs our understanding and our help, Rushdie says, exploring the lives of hijras in Mumbai. Dalrymple explores the inexplicable devdasi tradition in north Karnataka: pre-puberty girls who are dedicated to the goddess, their unusual lives and social standing, and how they come to terms with their fate.

Mukul Kesavan writes about men who have sex with men (MSM) in Bangalore. While the kothis (the feminine) among them are recognisable, the panthis (the male) remain invisible. Male sex workers talk about the married men who seek them out. Vikram Seths poem on AIDS and the story behind the poem are intensely personal. As someone who has been open about his bisexuality, his has been a powerful voice on gay rights in India. Siddharth Dhanwant Shanghvi, writer in his 20s who is being hailed as the the new Salman Rushdie and Arundhati Roy, tells the story of a young gay filmmaker who is the toast of Mumbai society. Shanghvis protagonist divides his time between the US and Mumbai, is open about his gay identity but tells very few about his HIV status.

Writers explore the pain and heartbreak of their protagonists. Panthis are treacherous bisexuals, the kothis tell Kesavan, therefore longterm relationships are not possible and they must resign themselves to a life of casual sex and sex work to affirm their womanliness. Many of the kothis recount being sodomised as children. For Shanghvis young filmmaker, to add to HIV and ailing health, there is the heartbreak of professional failure. A close friend who did not know he was HIV-positive grapples with the truth after his death. Why did he not tell me, did he not trust me, she wonders.

People living with HIV often say that disclosure to friends and family is one of the most difficult challenges. Disclosure is important for their well-being, because otherwise the secrecy of being infected adds to the guilt, shame and self-stigma they must deal with, they say. And yet, there is fear--of stigma and rejection and also of causing hurt and pain. Thats probably one of the reasons those who work on AIDS say as a society, it is important for us to talk about AIDS, deal with it, confront it. We are in it together as Amartya Sen says in his foreword to the anthology.

While most of the pieces are gripping, some fail to live up. An interview with a doctor from Nagaland recounting his journey is one-dimensional. The story on AIDS orphans over-emphasises one single point that these kids are regular kids who laugh and play, enjoy singing and dancing, go to school. One would have liked to know more about what growing up means for children who have not known a world without AIDS, the difficult questions they ask of caregivers and counselors.

The anthologys success is the landscape it covers--geographically, socially, culturally. From the fringe populations to high society, communities steeped in tradition to middle-class, from Ukhrul in Manipur to Belgaum in Karnataka. Prashant Panjiars powerful photographs tell their own story. Much has obviously gone into the fine editing--ensuring accuracy of data, appropriate representation of high risk groups, adding factual or quantifiable data where needed as footnotes.

It is being called Indias first charity book. There have been similar efforts before though not on the same scale for instance, Penguins A Poem for CRY in 2006. AIDS Sutra is the first book where such a range of authors have written wholly original pieces. We are also paying a much higher than usual royalty towards the fund that Avahan has created for the book. So it does make this the first truly proper charity book in the country, says Chiki Sarkar of Random House India. Response to the book has been excellent, adds Sarkar, with 6,000 copies out in the stores and expecting reorders.

AIDS Sutra deserves praise: the writers who wrote it and the editors who put it together. The mastery the writers have over their art enables them to tell the story of this side to India rarely seen before with empathy and compassion.