"What are you looking for in this place? If you are hoping to find answers here, you are in the wrong place. The only worthwhile thing you can hope to take back from here is questions," says the serious, bespectacled Justice L R Maravi, a sessions judge in Gondia district, Maharashtra and a Gond community leader. One hardly knows how to respond to this staggering but forthright piece of advice. What kind of answers can you expect anyway in this place where everything refuses to conform to your ideas of what they ought to be?

It is Maagh Purnima day, and we are at the annual Kachhargarh tribal fair in the deep interior Salekasa tehsil of Bhandara district, Maharashtra. The fair is held to celebrate the day when, in Gond mythology, the children of Mata Kali Kankali (not to be confused with the Hindu deity Kali), mother goddess of the Gond people, were rescued from a cave by the Gond religious leader Kari Kupar Lingo and his sister Jango Raitad.

As we thread our way through thick crowds towards the little village of Dhannegaon located at the foot of Kachhargarh hill, Dr Motiram Kangali, a prominent Gond community leader and head of the Gondi Punem (religion and culture) Mahasangha -- the apex religious body of the Gonds, updates us on the history of the fair. Kangali is with the Reserve Bank of India and is a Ph D. "In the year 1976 some of us, then students active in the tribal students movement, read about this fair in the books of Russle and C U Wills." Kangali, and two of his friends K B Maraskole and Sheetal Markam, (who later went on to form the Gondwana Mukti Sena, one of the constituent bodies of the Gondwana Ganatantra Party) visited the place out of curiosity. "We found that the fair had shrunk from the grand affair it once used to be to nearly a non-event, with hardly 500 people visiting the spot annually."

After visiting several other Gond pilgrimage centres in Central India, the group selected Kachhargarh originally known as Koili Kachar Lohgarh, as the most convenient spot where Gond tribals from Central India, Orissa and Andhra Pradesh could be brought together under a common identity. "It was also around the same time that we realized that there was no written documentation of Gond history, culture, mythology and ritual," says Kangali. This prompted him to take up the work of research and documentation.

It was ten full years after this first visit, from 1986 onwards, that the fair started being held at the present large scale. The organisational activity that went into the fair also led to the formation of the Gondwana Ganatantra Party (GPP), the political organisation of the Gond people. Today, as many as 3-4 lakh Gond tribals from the above-mentioned states visit the fair over three or four days around Maagh Purnima time. The number of non-Gonds is negligible. Mostly, it is journalists and social observers or just curious urbanites. There is no tourism value to this cave or fair yet.

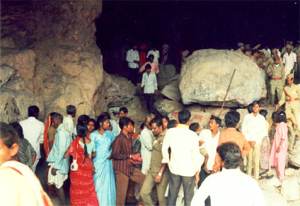

![]() People hovering at the entrance of the sacred Kachhargarh cave. Pic: Aparna Pallavi.

People hovering at the entrance of the sacred Kachhargarh cave. Pic: Aparna Pallavi.

Within an hour of arrival, we commence the three km walk to the sacred Kachhargarh cave the most important part of the pilgrimage. The last stretch is a difficult climb over a jagged hillside dotted with ancient trees. It is awesome and breathtakingly beautiful to the eyes, and a torture to limbs long habituated to urban ease.

But it is worth the trouble after all. The ancient cave, with its dark, damp walls, and the cool, heavy air that pervades it, belongs to another time. Its stream is a not-very impressive trickle in February, but it swells to a torrent during the rains. It is too dark inside to trace the stream's origin, but the gurgling sound inside the cave is enchanting. Deep and wide enough to accommodate some 20,000 people at once, Kachhargarh cave retains its timeless quiet despite the presence of a few hundred people in it.

Even if one misses the religious or mythological significance, there is no way one can miss the spirit. For once, we are back to the days of the earth's youth. Here is meaning. Here is beauty. Here at last you learn the meaning of the words 'peace that passeth understanding.' Here time does not exist. Here all questions dissolve, and so do answers. There is nothing to look for any more, and nothing to hold on to either. If only you could stay in this place and this state of mind for ever, things would be all right.

But it is getting dark, and we have to get back down. Back to today.

Down to the tiny hamlet of Dhannegaon, whose every home is an open house during the three days of the fair (February 11, 12 and 13 this year). "You don't have to know the residents," says Chandralekha Kangali, "You can camp in anyone's courtyard, cook food, eat, sleep, and stock your luggage." Over tea, Maharashtra state chief of the Gondwana Ganatantra Party, Raje Vasudev Shah Tekam says, "This is mainly a cultural and religious fair. We Gond people have lost our identity, our culture and religion we have become a scattered people. Through this fair we want to refresh our understanding of these things, and rediscover our identity and dignity as one people."

The GPP is not politically very strong, at least yet. Hari Singh Markam was once elected to Parliament in what is now Chhattisgarh. Some people have been elected at the local level, again in Chhattisgarh, and very few in Madhya Pradesh.

The Gond religion is nature-based. The Gond style of social organisation is based on the 'saga' (clan) system. Under this system, which was established by the Gond religious leader Kari Kupar Lingo, there are 12 'sagas' or groups which are further divided into 750 'kur' or clans.

Each clan is bound by the Gondi religion to protect one tree or plant, one animal and one bird. The clan names are based on this categorisation. For instance, the name Markam relates to the mango tree, while the name Kangali refers to a certain climber.

The marriage rules of Gond tribals are also based on this organisation. All the clans in one 'saga' worship a certain number of deities, ranging from 1 to 7. Intermarriage between members from different clans is permitted if one clan worships an odd number (visham) of deities and the other an even (sam) number. The clans with odd and even numbers cannot intermarry.

In several parts of India, Gond communities have forgotten this system of marriage. At present, research is on to rediscover the vital details of this system. Community leaders feel that the reestablishment of this system is vital to the identity of the Gond community.

Women: Gond mythology has it that Kari Kupar Lingo's sister Jango (rebel) Raitad started a social reform movement for the rights of women, after which widows were given rights to maintenance in the marital home as well as remarriage. Also, a woman's consent is important for marriage. Women have equal educational status.

•

Caste panchayats and Gond women

•

Convention of adivasis and nomads

"We Gonds want to resurrect our social and religious structure -- the system of 12 sagas and 700 kur (clans)," says Anandrao Madawi, mursenal (chief) of the Jagatik Gond Saga Mandi, the apex body of the Gond tribal panchayats, "We want our own state, our own language, our own punem (religion). We want others to recognise that we exist."

A quick ramble in the little makeshift market the kind that inevitably springs up at such places -- makes for interesting observation. There are several stalls selling books on Gond religion, culture and even the basics of the spoken language. "A lot of our people have forgotten the Gondi boli (language)," explains Kangali. His books are being sold under the name Motiravan Kangali a small but startling piece of tribal self-assertion against Hindu assimilation. Kangali is known by this first name in the Gond community, and retains his original first name, Motiram, at work.

At other stalls, Gond religious symbols are for sale some emblazoned on T-shirts, some framed together with Hindu symbols. Stalls selling traditional Gond paraphernalia of worship exotic roots and herbs sit cheek by jowl with others selling incense, coconuts, tulsi and rudraksha beads. Several stalls selling cassettes and CDs of Gondi songs are doing brisk business. But beneath their glossy, faux filmi covers, (one has a picture of a popular Hindi film actress) it is impossible to determine which ones are authentic and which have been created for the market.

"Each year the number of people at the fair goes up," quips a senior journalist from Nagpur, Jagdeesh Shahu. "But each year you see lesser and lesser traditional clothes," he adds.

"It is certainly not easy," admits Tekam, "Our people want to recover their religious-cultural identity, but the Hindu and global cultures do have an insidious grip over their minds. There are contradictory pulls."

But there are positive signs too, says Kangali. At one time Hindu assimilation was so complete that Gond people were ashamed of their identities, and even clan names had been modified to sound like Hindu surnames, he points out. "But since the resurrection of this fair, a large number of people have resumed their original identities and clan names. That is a beginning, at least," he says.

Meanwhile some Angadevs have also descended from the cave. The Angadevs are very small idols, 33 in number, and symbolise the children of the mother goddess who were rescued by Lingo and later became the emissaries of his message. They are put on ornate palkhis (palanquins) and brought to the fair. The original idols are very small. It is not clear if they always accompany the palkhi, and the palkhi itself is the symbol of the Angadev, I am told.

An authentic, unadulterated cultural ritual unfolds. Clad in clean white cotton half shirts, half dhotis and head-scarves, -- proper Gondi costume -- the bearers of the palkhis dance around the Gond flag to rhythmic drum beats. Men and women overcome by hypnotic emotion whirl round and round in the spaces between. Since there is no fixed time of the Angadevs coming and going, the dance takes place as and when some idols are ready to return.

![]() One of the palkhis descending from the hill. Pic: Aparna Pallavi.

One of the palkhis descending from the hill. Pic: Aparna Pallavi.

7 pm. Time for today's session of the Gond religious conference. The huge marquee, with a capacity of at least 20,000 people, is crammed full. They squeeze tighter inside the marquee and spill our over the huge ground at the centre of which the marquee has been erected. By midnight, the crowd will have swelled three times this size, say community leaders, and a visual estimate indicates that this may not be an exaggeration.

We are huddled on the dias -- which appears to be an open-for-all area where people come and take up space at will -- with a motley crowd of about 70 people. The speakers are a mixed crowd of politicians, religious leaders, community elders and others whose identities are not very clear.

Nothing is more mixed up than the speeches that are made. In the very beginning, the announcers have instructed all speakers to stick to religious matters. But talks that start with the fine points of religious precept, practice and ritual, inevitably slip off into subjects with deeper socio-political resonance. Language, culture, identity, exploitation, the need for organisation and political self-assertion, the need to resist cultural assimilation -- all interlace with rhetoric, religion, myth, ritual and even superstitious mumbo-jumbo to form one complicated fabric in which it is impossible to identify or sort out the different strains of thought.

The resolutions that are passed are definitely not religious -- inclusion of the Gondi language in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution and Gondi as an optional subject in schools in the seven states with a high proportion of Gond population. Community leaders say there are about 14 crore Gonds in the country -- twice the population of Maharashtra.

One is tempted to be judgemental -- no clarity, no coherence, no order. No one knows what they want. Why do they want to hold a religious fair if they are going to talk politics?

Or is it so? How much coherence can you reasonably expect from a people who, along with their fellow adivasi communities, have been victims of ruthless uprooting, exploitation and assimilation for centuries? A people who are mostly impoverished, uneducated, have no recourse to social or political power or sanction? A people who must create a past, present and future; a history, identity and aspiration for themselves -- an entire discourse - all at once? Is twenty years enough for such a mammoth task?

The questions do not allow easy responses. The realities are complex and multilayered, and concerns that look overly simple one moment are mindboggling the next.

Or maybe we are just missing the desperate undertone to everything else -- get together to survive! Hold on to each other -- any link, any reason will do. Just stand together.....

Meanwhile it is midnight. On the dias and in the marquee, people are curling up to sleep where they can, even as a cultural programme is announced. There is nothing to do but to follow suit.

As I work my tired body into a semi-comfortable posture between other sleeping bodies, Justice Marawi's eyes are suddenly just two inches away from my own. "Did you get any answers?" he asks in a whisper. Did I? I shake my head. "Pay attention to the questions, though," he whispers back, "Who knows one day they will lead to answers."