In a country like India where rights violations are common, the campaign against the death penalty remains on the sidelines. Much like economic, social and cultural rights tended to be seen as second-level rights, the death penalty seems to be a second level concern amidst the vastness of other violations of human rights particularly the thousands of extra-judicial killings and disappearances and the countless cases of torture. Yet this is a not a numbers game and the death penalty is emblematic. It symbolises the power of the State to end the life of a person by a process that is legally sanctioned, and officially sanitised. To paraphrase Albert Camus, it is theoretically defensible murder on the part of the State.

While this may not be a numbers game - numbers count all the same. Till recently we were informed that there had been 55 executions till date in post-independence India. We don't quite know where this number came from. Most in the media clearly didn't ask. Others, who didn't know of this magical figure, said nothing at all. Instead they preferred a blander disclaimer that the government did not collect/provide statistics on executions in India. Those who wrote that the government did not provide data were probably right. But those who wrote that the government did not collect such information clearly did not realize their claim would not stand for long. Either way, the only figure floating was "55" and initially no-one contradicted it, not least the government.

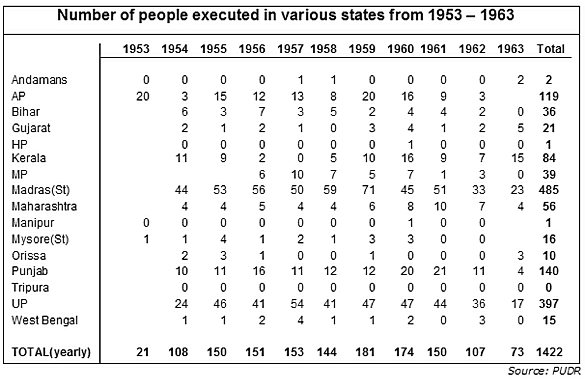

Thankfully not all of us believed this. Recently the Peoples Union for Democratic Rights announced that it had unearthed government records which revealed that 1422 executions had taken place in 16 Indian states from 1953 63. This information comes from Appendix 34 of a 1967 report of the Law Commission of India a public document that is freely available. Since PUDR's announcement, several media have reported the 1422 number.

The government itself has not yet responded to this 'discovery', but past record suggests that it will maintain its silence. After all, silence has worked for so long.

But the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) did respond. It said that PUDR's claims were exaggerated (ignoring that these were not PUDR's but Law Commission figures) and stated that they would wait for the government to ask them to look into this matter before further comment. The Law Commission too has preferred not to comment.

A lot of questions need to be raised at this stage - if all this information was available in a 1967 document, why was everyone unaware of it? Most likely answer - not everyone was unaware (NCRB etc) of these and other statistics. Why does the State maintain such a secret approach to past executions? Is there something more that we don't know Is there something the State doesn't want us to know? It appears that information on executions has become a de-facto state secret.

There are other questions as well. The Law Commission statistics cover only a decade from 1953 to 1963 and only 16 states. What about the other states? What about executions prior to 1953? Once again some media-persons inform us that Nathuram Godse was the first person to be executed in independent India in early 1949. Given the now shaky record of the media on executions one cannot be certain of the authenticity of such a claim.

Furthermore we must keep in mind that this was an era when death sentence was the norm for a number of crimes and not an exception - clearly then the number of people hanged from 1947 to 1952 must be high as well. What about figures from 1964 onwards? The NCRB has only published execution figures post 1995 that leaves at least 30 years unaccounted for. While the general belief is that executions reduced after an early 1980's "rarest of the rare" judgement, we would like to know for certain.

Even assuming that executions reduced sharply after 1980, that still leaves executions during 1950-1980 for which the government needs to provide numbers. Taking an average of 100 executions a year from 1950 - 1980 gives us a total of 3000 executions. But given that the average between 1953 and 1963 was 142 per year, the final figure of executions in India could be anywhere between 3000 - 4300, and these are just estimates.

Other than the number of people executed between 1953-63, the tables in the Law Commission appendix are devoid of other information. Who were those people? What crime did they commit? Did they even have lawyers? Were their cases appealed to the Supreme Court? We dont know - and we are unlikely to know unless the State starts revealing this information. The bulk of these cases are unreported judgements not even included in the various collections prepared by All India Reporter, Criminal Law Journal and even the various local state specific journals.

• Sentenced to die, non-unanimously

• Myths about the death penalty

The PUDR discovery may reignite the sporadic debate on the death sentence in India. It would be a rare debate that is not focussed on one case alone and that might allow a broader, more holistic view of the death penalty. It is however important now that this debate be conducted in an informed climate where facts and figures are made available by our central government.

It is unlikely that this information will come easily from the State. But the immediate task ahead is to lobby and pressure the Ministry of Home Affairs to make this information available. The National Human Rights Commission too could play a role in raising questions. Given the past silence of various governments and the harsh truth that the death penalty has not been a subject "hot" enough to retain media interest for long, maintenance of pressure needs a well-coordinated campaign for information and eventual abolition of the death penalty.