Theres a curious irony that every year March 8 is celebrated as International Womens Day with growing enthusiasm, even as the status of women in Indian society remains static, if it hasnt deteriorated. Of course in a nation which has developed a unique capability for celebrating ritual, there was no shortage of politically correct speeches on the day. Last month President A.P.J. Abdul Kalam stressed that womens rights are the edifice on which human rights stand; politicos aired their displeasure at the Jammu and Kashmirs Permanent Disqualification (Residence) Bill; Air India operated a flight with an all-woman crew and a few special women's empowerment schemes were announced.

But beyond tokenism and displays of lachrymose sentimentality, the ground reality is this: the national male-female ratio is an alarming 1000:933; only 54.16 per cent of the women are literate; close to 15,000 women succumb to dowry torture annually and 130,000 women face the worst forms of assault upon their mental and physical well being every year.

![]() Even as politicians and the urban middle class indulge in helpless hand wringing, educationists and social scientists are increasingly veering around to the view that persistent gender biases and oppression of women are rooted in post-independence Indias failed education system, particularly in the conspicuous failure of successive governments at the centre and in the states to universalise elementary education. According to the Union governments own (suspect) statistics 35 percent of the nations adult population is comprehensively illiterate the majority of them women. And its pertinent to note that literacy is less than synonymous with education.

Even as politicians and the urban middle class indulge in helpless hand wringing, educationists and social scientists are increasingly veering around to the view that persistent gender biases and oppression of women are rooted in post-independence Indias failed education system, particularly in the conspicuous failure of successive governments at the centre and in the states to universalise elementary education. According to the Union governments own (suspect) statistics 35 percent of the nations adult population is comprehensively illiterate the majority of them women. And its pertinent to note that literacy is less than synonymous with education.

Inevitably, there is no shortage of informed opinion that education of girl children is the prerequisite of national socio-economic development. Comments UNICEFs State of the Worlds Children Report 2004: "Girls education is the most effective means of combating many of the most profound challenges to human development. Education is vital in emergencies For communities, strategies for providing girls to complete their education yields benefits for all." Yet in the developing nations of the third world 135 million children between the ages of seven and 18 have received no education at all and of them more than 60 per cent are girl children. This gender disparity in education translates into other deprivations such as food, sanitation facilities, safe drinking water, shelter and information.

Well-known environmental activist and physicist Vandana Shiva has no hesitation in linking the issue of female education rather the lack of it to the maladies of the Indian social order. "Lack of education among women has caused the patriarchal system to grow strong roots in India. Educating women about gender equity and economic sustainability is universal education. While in the patriarchal system male education is given primary importance, womens education benefits many and is all encompassing. We should model the economy on the premise that educated women help to build equitable and sustainable societies," says Shiva.

A growing awareness of this reality is perhaps why gender parity in education is one of the six goals of the Education For All (EFA) programme, endorsed by 164 countries at the World Education Forum in Dakar, Senegal, in 2000. The attainment of this goal by the 2015 deadline remains a distant prospect as highlighted by the 2003 EFA Monitoring Report which states that 54 countries including 16 in sub-Saharan Africa as well as Pakistan and India will fail to meet the deadline.

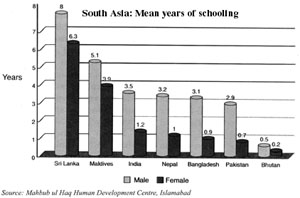

Against this backdrop its hardly surprising that India is positioned almost at the bottom of the heap in measures of the Gender Parity Index which traces the growth of female enrollment in schools. While a GPI of 1 indicates perfect parity between the sexes, India measures 0.83 at the primary level, a figure that is only slightly better than worse performers like Mali (0.72), Liberia (0.73) and Pakistan (0.74). And to add to this dubious distinction, India figures nowhere in the list of countries (including Nepal and Pakistan) that have shown the greatest improvement in girls enrollment.

However its important to note that although gender disparities in education are particularly accentuated in the Indian subcontinent, they are not peculiar to it.

Bias against womens education is operational worldwide in varying forms. For example in Poland, school textbooks routinely stereotype women as mothers and housewives. Likewise in Hungary most school texts dont portray women outside their home environment, and in Azerbaijan, they explicitly condemn women who work outside the home. The Indian bias against womens education dates back to the colonial period, when only a minority of upper caste and middle class women were allowed access to formal education, and even then, they were confined to separate curricula, often focused on domestic skills and moral and religious education.

Niranjan Pant in his book Status of Girl Child and Women in India explains why educating the girl child remains a low national priority: "A boys education is generally viewed as a possibility of increasing the earnings and status of the family. The value of a daughters education is gauged in terms of her marriage prospects. However, marriage of an educated girl carries its own practical difficulties, and the benefits of her education in any case are seen as going to her husbands family. Therefore the desire or motivation to send girls to school and ensure its completion is circumscribed by high economic costs, unfriendly school environments and social sanctions."

But despite a social environment which is indifferent if not hostile to womens education, within the councils of government in New Delhi there is growing awareness of the vital connection between womens education and the national development effort. In the Sixth Plan (1980-85), the eradication of illiteracy, income-generation schemes and non-formal education for poor women were accorded high priority. In the Seventh Plan (1985-90), women were identified as a critical human resource requiring skills training and development inputs. The 1992 Programme of Action, based on the National Policy of Education, 1986 and the Education for All initiative of 2003 also stressed the need for interventions for womens education and empowerment. These documents high on rhetoric, are said to herald a major shift in official policy as they acknowledge education as a prerequisite of gender equality.

IAS officer Kalpana Awasthi, Uttar Pradeshs project director, Education For All, explains the policy shift of the Union and state governments towards womens education. "From an overarching emphasis on getting all children into school, policy issues are now focusing on specific interventions such as residential camps for girls and strengthening anganwadis so that girl children arent denied education because of household duties. There is greater use of communication and advocacy tools such as kala jathas with specific targeting of messages. Ma-Beti melas, the model cluster development approach, life skill camps, and gender sensitive books are some other innovations. This new strategy is more wholesome and is devised to mobilise and empower the girl child," says Awasthi.

Inevitably some solutions have spawned newer problems. For instance the provision for separate schools for girls has also resulted in the prescription of separate curricula for them. Despite directives of the Union government, several state governments continue to prescribe different but rarely equal curricula for girls at the school level. Girls institutions are content to have them learn home sciences, needlework and fine arts with no provision for science and mathematics. Besides disadvantaging girls in terms of career choices available to them, this also adversely affects the supply of women teachers in these subjects.

Little wonder that despite high-sounding rhetoric incorporated into the nations increasingly irrelevant five-year plans and education policy statements, on-the-ground progress in terms of empowering women through access to qualitative education has proved elusive. In rural India the gender gap in literacy is 22.27 percent and 16.8 percent in urban India. Over a third (34.3 percent) of girl children drop out before completing primary school and of the estimated 65 million out-of-school children, 40 million are girls. For states on the bottom rungs of these indicators, the numbers are terrifying. In Indias most populous state, Uttar Pradesh (pop. 160 million) only 42.98 percent of women are literate, this dips to a mere 19 percent in UPs Shravasti district. In Bihar, which is at the very bottom of the list, only 33.57 percent of girl children are literate.

![]() Down south with the exception of Kerala with 87.86 percent female literacy,

the statistics are only marginally better. Tamilnadu is a distant second with 64.55 percent

while in Andhra Pradesh only 51.17 of women are literate. Yet Thilakavathi Bhaskaran, principal, MGR Janaki College for Women, Chennai says that the southern states tend to be more women friendly. "Historically, the position of women has been much better in the southern states. The Manu Shastra did not originate here, therefore pioneering work on womens education began in the south for two reasons. First, the British established their power in Madras early on and established Queen Marys College in Chennai in 1914. Secondly missionaries promoted schools for women in the 19th century and the first medical college for women was established in the Madras Presidency. In addition, social reform movements in the south such as the Dravida Kazhagam in Tamilnadu and the Leftist movement in Kerala played an important role in the education of women."

Down south with the exception of Kerala with 87.86 percent female literacy,

the statistics are only marginally better. Tamilnadu is a distant second with 64.55 percent

while in Andhra Pradesh only 51.17 of women are literate. Yet Thilakavathi Bhaskaran, principal, MGR Janaki College for Women, Chennai says that the southern states tend to be more women friendly. "Historically, the position of women has been much better in the southern states. The Manu Shastra did not originate here, therefore pioneering work on womens education began in the south for two reasons. First, the British established their power in Madras early on and established Queen Marys College in Chennai in 1914. Secondly missionaries promoted schools for women in the 19th century and the first medical college for women was established in the Madras Presidency. In addition, social reform movements in the south such as the Dravida Kazhagam in Tamilnadu and the Leftist movement in Kerala played an important role in the education of women."

Within this overall dismal womens literacy scenario and its pertinent to note that literacy is far from being synonymous with education women within some of Indias myriad communities are doubly disadvantaged. According to an ORG-Marg Muslim Womens Survey conducted in 2000-2001 in 40 districts of 12 states, almost 60 percent of the 60 million Muslim women in the country are illiterate with the enrollment percentage of Muslim girl children being a mere 40.66 percent. As a consequence the proportion of Muslim women in higher education is a mere 3.56 per cent, lower even than that of scheduled castes (4.25 percent).

"The whole problem of mass illiteracy among women is because the Union government doesnt regard education as the fundamental right of every citizen. And it is precisely because of lack of education among women that domestic violence is a common phenomenon in Indian society. Id say more women are killed in India in cross-bedroom terrorism than soldiers on battlefields. The gravity of the issue requires it to be addressed by mainstream political parties and not merely by womens organisations. The politicisation of womens organisations is the only way towards empowerment of women," says Brinda Karat, general secretary of the Delhi-based All India Democratic Womens Association.

The misplaced fascination of Indian educrats with numbers is also playing havoc with the cause of womens education indeed with the cause of education in general. Comments Johnson Fernandes, programme coordinator, Child Rights Unit of Yuva India, a Mumbai based NGO which runs support schools and is also involved in advocacy on childrens issues: "Under the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan any individual who has passed class X or XII can start a school. It need not be a formal, full-time school and can be located anywhere in a temple, at home, or under a tree. The government pays this person about Rs.800 to Rs.1,000 per month. This way the government can accumulate statistics that show that all children, including the girl child are in school. This is a misdirected shortcut. Such part-time schools merely marginalise children because they dont provide even minimum quality education. These para schools actually promote child labour, because the child, especially the girl child who attends only three hours of school is free to work the rest of the time and is at a high risk of dropping out. The reality is that children in such ad hoc schools are not getting educated at all."

Under the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan any individual who has passed class X or XII can start a school. It need not be a formal, full-time school and can be located anywhere in a temple, at home, or under a tree. The government pays this person about Rs.800 to Rs.1,000 per month. This way the government can accumulate statistics that show that all children, including the girl child are in school. This is a misdirected shortcut.