Close to half of employed Indians work in agriculture. The value added in agriculture – the amount by which the value of output exceeds the value of intermediate inputs – is an indication of the health of the agricultural economy. In 2012, this was Rs 63,000 per agricultural worker, less than a fourth of the average figure for non-agricultural workers. At about Rs 170 per day, this was barely higher than the minimum daily wage of unskilled agricultural labour in some states.

It must be kept in mind that ‘value added’ is only an average figure and that different categories of agricultural workers - large farmers employing labour, small farmers tilling their own land and wage labourers - will have differing claims on the value added.

For the millions trapped in agriculture, the possibilities of escaping poverty depend on the rapid growth of agriculture and the availability of jobs in more productive sectors outside. There are major impediments to the former, chief among them being the fragmentation of land into very small holdings, making the mobilisation of capital for development extremely difficult. The choice of the latter is contingent upon more better-paying jobs being available outside agriculture for the ‘unskilled’ farm worker.

Such existential crisis faced by the Indian peasant is not unique. All across the world, the presently industrialised nations, had at some period in their history, a greater part of their workforce engaged in agriculture under conditions of low productivity in comparison with industry. Industrialisation progressed as labour migrated from agriculture.

This migration in turn opened up the path for growth in agriculture through productivity increases, eventually narrowing the gap in productivity between agriculture and industry. The rapid change in these economies, from a stage in which agriculture accounted for the lions’ share of employment and gross domestic product (GDP) to one where industry took its place, has been termed a ‘structural transformation or shift’.

Structural shifts from agriculture to industry happened not only in the industrialised countries of the west, but also in Asia – in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. In most countries after the shift, the share of manufacturing in employment increased to over 30 per cent. In the industrial powerhouses Britain and Germany, this share reached 45 per cent and 40 per cent respectively, at its height. Since then, there has been a decline in the share of industrial employment in these countries. But it must be noted that the second structural shift in employment, this time from industry to services happened only after industry had attained a share of about 50 per cent in the GDP.

Closer home, China too, it appears, is also on its way to a structural transformation with manufacturing accounting for about 33 per cent of its GDP ( industry for 46 per cent). But India remains way behind in terms of the development of industry.

Chart prepared by Kannan Kasturi

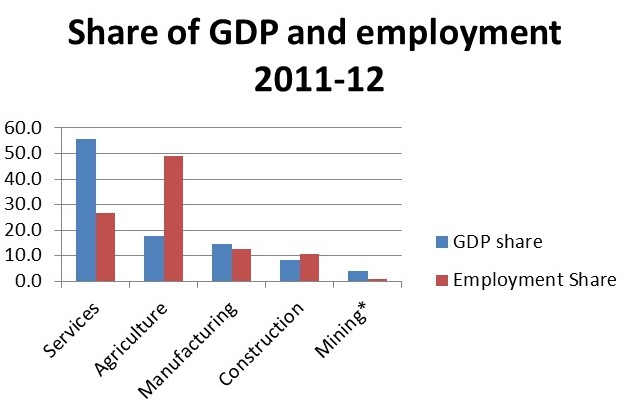

Manufacturing had a share of 14.4 per cent in GDP in 2011-12 and industry as a whole had a share of 26.7 per cent. The above chart draws attention to the basic structural imbalances in the Indian economy – the great discrepancy between a sector’s share of contribution to GDP and its share in employment, across sectors of the economy. (The share of other non-manufacturing industries except for construction - such as electricity, gas and water distribution - has been clubbed with mining in the above chart)

Has a structural shift begun in India?

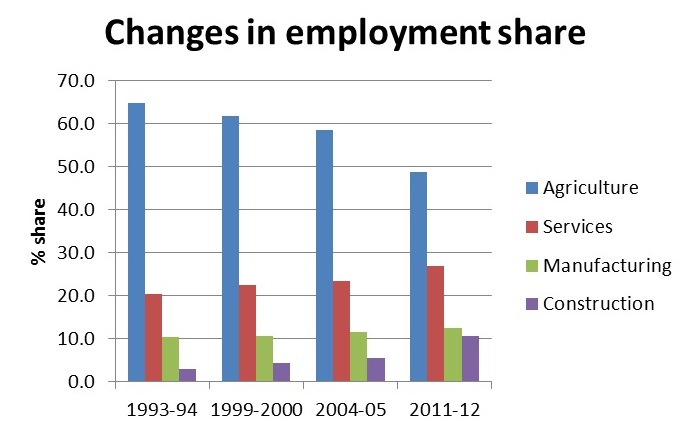

Claims have been made recently that a structural shift in employment out of agriculture, though greatly delayed, may finally be in progress in India too. The claim is based on the sharp 10 per cent drop in the share of agriculture in total employment between 2004-05 and 2011-12, and the fact that the absolute numbers employed in agriculture have declined for the first time since 2004.

The chart below shows the relative share in employment of different sectors of the economy over the years. The data is from the National Statistical Survey Organization (NSSO) and the employment in non-manufacturing industries (other than construction) has been omitted as it is insignificant.

Chart prepared by Kannan Kasturi

The chart taken at face value seems to show that Indian peasants are moving out of agriculture at an accelerated pace since 2004. The increase in the share of employment has been mainly in the construction sector and to a lesser extent in services. Employment share of manufacturing has increased only marginally. A closer examination of disaggregated NSSO data for agriculture throws more light on the shift out of agriculture.

Women leaving the labour force

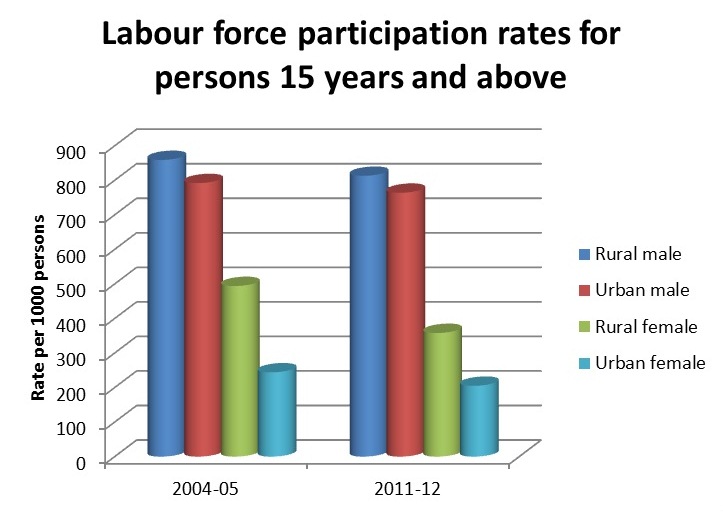

The chart below shows the decrease in recent years in the labour force participation rates (LFPR) - the number of people in a category who look for employment out of every 1000 - for rural and urban Indians aged 15 and above. (The same trends have continued into 2012-13 as per labour ministry surveys.)

Chart prepared by Kannan Kasturi

One reason for the decreasing LFPR is the increasing enrolment of youth between 15 and 24 in educational institutions. This affects both men and women and more or less accounts completely for the LFPR decrease among men. That still leaves the issue of women leaving the labour force.

Over 80 per cent of women leaving the labour force belong to rural India. The most plausible explanation for rural women leaving agriculture and retreating to household duties runs along these lines. Most of these women are from the poorest rural households. These are the households of marginal farmers and casual labourers from which the men have migrated out of the village in search of casual jobs in construction. Rural women traditionally work together with their men folk, either as unpaid family workers or as casual labour and have stopped working as they can no longer accompany their men folk.

The falling LFPR, predominantly affecting rural India and thereby agriculture means that the fall in the employment share of agriculture is not entirely due to workers shifting to other sectors. A significant part is due to rural girls and women withdrawing from agriculture.

Agricultural labour is not being ‘pulled’ to jobs in expanding manufacturing in industrial centres; rather it appears that it is being forced to take up seasonal casual work to avoid further deterioration in standards of living. The households of these migrant workers are still in the villages. For all these reasons, it is difficult to conclude that a structural transformation similar to that seen in industrialised countries is under way.

Jobless growth

Going by the historical experience of other countries, manufacturing jobs are the key to facilitating an employment shift out of agriculture. Is manufacturing job growth stagnant because of poor growth?

The following table shows the average annual growth of jobs and of value added (same as the contribution to GDP) in the different sectors of the economy over the most recent period for which both sets of data are available.

|

Average annual growth rate 2004-05 to 2011-12 |

||

|

|

Real GDP (%) |

Employment (%) |

|

Manufacturing |

8.9 |

1.5 |

|

Construction |

8.8 |

10.1 |

|

Mining* |

4.9 |

4.3 |

|

Services |

10.0 |

2.5 |

|

Total non-agricultural |

9.4 |

3.5 |

Thus we find that from 2004-05 to 2011-12, India’s real non-agricultural GDP grew by an average 9.4 per cent per annum, but employment therein grew only at 3.5 per cent. Services and Manufacturing were the fastest growing sectors at 10.1 per cent and 8.9 per cent respectively. However, they added jobs only at 2.5 per cent and 1.5 per cent respectively.

Clearly, GDP growth encompassing both manufacturing and services did not translate into employment growth. The answer to why growth in manufacturing is practically jobless growth must be sought in the structure of Indian manufacturing and its markets and is beyond the scope of the present article.

But what is amply clear is that growth of the GDP is no guarantee of employment growth. A large part of the poverty-ridden agricultural workforce awaits the creation of factory jobs to transition out of agriculture. Any government that claims to represent the peoples’ best interests must aggressively focus on creating productive jobs in industry.

References: Sources of data used in this article as well as pointers to scholarly articles on this subject may be found in the authors’ blog.