Bilaspur, July 2002. All over Chingrajpara, in the narrow galis between the houses, in the tiny spaces near the ponds, there are children to be found, playing. Less perhaps than in June but still easy to find. The school session commenced at the beginning of the month but that is not reason enough to give up hopscotch or marbles, not just yet.

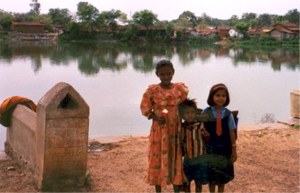

![]() From left, Lacchmi, a member of the hopscotch group, in the orange frock, her brother and another girl in the neighbourhood who's just back from school. Pic: Ashima Sood.

From left, Lacchmi, a member of the hopscotch group, in the orange frock, her brother and another girl in the neighbourhood who's just back from school. Pic: Ashima Sood.

Halfway into the month, late one morning at the nearby primary school in Bilaspur's Ward No. 41, the mystery of the playing children begins to lift somewhat. The teachers, it turns out, are busy poring over their income tax forms in the passageway. In the two classrooms behind them, the children, from classes one to five, are raising a ruckus.

After I am introduced as the 'madam from Delhi', the teachers are duly respectful. I am offered a seat and possibly tea. Mindful perhaps of my presence the teachers take turns to attend to the children. A lady teacher indifferently corrects the slates a few of the children bring to her, laying outsize crosses against the figures she deems incorrect. Two weeks into the term the new textbooks have still not arrived, the teachers explain - there is nothing really for them to teach.

In its unpleasant odour of overflowing, perhaps non-existent bathrooms, in the seedy single-storied building, in the overcrowded classrooms, in its inadequately few and apathetic teachers in all of these facts, this government school in Chingrajpara could be a textbook case straight out of the well known 1999 Public Report on Basic Education in India (henceforth PROBE report). Yet unlike the 162 primary government schools in the PROBE surveys which covered the 'BIMARU' states of Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, the Chingrajpara school is not a rural school - far from it.

Chingrajpara is the largest slum in a city of slums. Seat of the High Court of the newly created state of Chhatisgarh (earlier part of Madhya Pradesh), Bilaspur is also home to some 49 slums, which house almost two-thirds of its 2.2 lakh population (1991 census). I am in Chingrajpara to do a livelihood assessment as part of the NGO ActionAid's slum development project called Asha Abhiyan. But in the meantime, when I go to talk to the adults about the ways they cobble together a living, the children hover in the background like bashful angels - but not to be overlooked lightly.

Why are the children in Chingrajpara not in school? What is needed to bring them there and more importantly, keep them there? As the turn of the century PROBE report had found for rural schools, and as I found here in the city, the answers are both unexpected and self-evident.

I. Nandu

At fourteen, Nandu has outgrown his angelic years but he is still very much at large, greeting me with a toothy grin whenever I go to meet his mother Geeta Sahu. An eleventh class pass herself and active member of the local Mahila Samiti, Geeta knows, more than most, the value of education. Yet when after failing a couple of times, Nandu refused to return to class sixth, there was little she could do. "Say then," she nudges Nandu, taking advantage of my presence. "Tell madam why you won't go to school."

Wisely taking heed, Geeta Sahu and her husband Vijay Kumar have transferred their younger children, a daughter in class fifth and a son in class three to a private school. Their ability and willingness to do this is unusual Vijay Kumar is a mobile vendor who dropped out of middle school but it is his better-educated, more resourceful wife who makes the decisions in their household.

For Nandu it is already too late. He has lost interest in whatever any school, government or private, might have to offer him. What Nandu needed to stay in school should have come entirely from the supply side of the schooling process. He needed an environment that engaged his enterprise and creativity and a system that would not subject him to repeated failure for its own malfunctioning. His is a cautionary tale of the de-motivating influence of a sub-standard school.

Now Nandu is starting, with his mother's help, on a kabadi business in the front room of their tiny two-room kholi. In return for orange-flavoured toffees or a few biscuits, he trades in the pickings of the neighbourhood children, mostly masses of liquor bottles discarded by fathers.

II. Lata

For thirteen year old Lata Yadav, who has just been promoted to class sixth, having grandparents and an aunt at home to take care of her three younger siblings is the key. As a girl, and the eldest girl, the risks that lie in the way of her schooling are very different from Nandu's. The PROBE surveys indicate that nearly two-thirds of girls that drop out of rural schools are withdrawn by parents, and the reason cited in more than two-thirds of these cases is that 'the child was needed for other activities', most often helping with domestic work and looking after younger siblings.

What helps her stay in the slum school is also the surprising vehemence with which her mild-mannered parents, father Kishen Yadav and mother Kumari, both unlettered vegetable vendors speak on the subject of education. Says Kishen, "I would rather go without a meal than have my child go to school without a textbook she needs." And then there are the signs that bespeak prosperity around this household the relatively spacious structure with an inner courtyard, the gold Kumari wears, the television, the cycle.

And despite what her parents say, not all is unproblematic for Lata early morning everyday before school, Lata walks with her mother a long round to hawk last day's unsold vegetables. She has failed twice already once in class two and once in fourth when all her family went to her uncle's during exam-time. And Lata's narration does not reflect the confidence of a child gaining mastery over her environment she likes school but finds it difficult. Of all her subjects, she likes environment (paryavaran) and hindi, but when I ask her to write her name she hesitates.

None of the top reasons cited by parents in the PROBE surveys for withdrawing girls from school apply to her she is not needed at home for domestic work, her parents can well afford her schooling and they evince at least some interest in her education. Yet for all their good intentions, Lata's parents do not have either the personal or public resources available to them to affect their child's schooling experience.

And by demanding accountability of teachers and the educational infrastructure, parental and civic involvement can make all the difference in educational achievement. This was the inescapable conclusion the PROBE team reached when it compared the BIMARU states to the amazing strides made by Himachal Pradesh. Starting at levels of illiteracy similar to the PROBE states in 1951, Himachal Pradesh cut down the proportion of illiterates in the age 10-14 to 10 per cent in 1991. But more significant was the progress the PROBE team found on school attendance, elimination of gender and socio-economic disparities and improvements in the sheer quality of schooling. As the PROBE team exclaims, 'Even eldest daughters in poor families go to school!'.

Lata may nominally stay in school but subject to an indifferent classroom environment with a poor pupil-teacher ratio, it is not clear if she is learning enough.

III. Lacchmi

Lacchmi can write her name, as she proudly demonstrates. She lives next door to Geeta Sahu, near the pond and happens to be one of the unchanging members of the hopscotch gang. With Nandu Sahu she manages a satisfactory trade in liquor bottles. The eldest of five siblings, she has never been to school.

Lacchmi should be about twelve, or maybe thirteen, says her father Devendra Sahu. Devendra is a short, thin, very fair man with unusually light eyes. His children have inherited his enviable colouring. Impressed with her complexion a few years ago, a woman had in fact offered to buy his middle girl Mita when she was a baby, he tells me with some pride. But he refused steadfastly. Even though his and his wife's earnings as hamaals (loaders) in the vegetable market do not stretch far enough to feed five children, a sixth is on the way.

On the day I meet their family, seven year old Anita, Lacchmi's sister, is over at Geeta Sahu's to ask if her class two books will do in class three as well. Her father cannot read to tell and he may not give the money for the new books either. Anita is the only one of the five who goes to school. Sometime after the woman offered to buy her, five year old Mita managed to burn her forefinger and thumb, reducing them to talons, and thus foregoing her chance at an education. Even now tagging along behind her elder sisters Lacchmi and Anita, Mita is blank-faced and expressionless.

Devendra is something of a domestic tyrant, his wife Kiran confides after her return late that afternoon. She is an unexpectedly beautiful, no-nonsense woman with a perpetually harassed air. She has been a hamaal since she was seven or eight, she says it is her family profession. Hugely pregnant, she still carries loads of 70-80 kg all day to provide for the evening meal. Her husband spends all of his own earnings at the local liquor shop every evening.

Unlettered herself, her children's education is the least of Kiran's concerns as it is, all her resources, physical and financial, go simply into providing for them. Her children continue to mill around her but sometimes, she is at the verge of snapping at them. Among other things, she is burdened by the dowry she has collect for Lacchmi's wedding.

Unburdened by that knowledge or any other though, Lacchmi maintains an unflagging good nature. She has her mother's sharp features and her father's colouring she might be pretty but for the layer of dust that covers her face and the reddish streaks in her tangled hair that suggest protein deficiency.

Like her mother Lacchmi speaks a barely decipherable Chhatisgarhi but she has the insatiable curiosity of a child denied the opportunity to learn. In half an hour she has almost as many questions for me as I have for her. She does not know even her birthday. But she has learnt to write, copying from her sister Anita's books.

Her daily routine has little space for her efforts. Everyday she has to get Anita ready, she says and send her to school. Then she has to cook, clean, take care of her brothers and sisters. She likes to eat and but also to cook. On Sundays she says, she goes to work with her mother but carrying the 10-15 kg baskets all morning makes her back hurt. When she stays home she gets to play Vish Amrit, Gilli Danda, and other games with unrecognizable names - Falli, Gadda and Dandak. She doesn't like to watch TV but when she does, seeing the children makes her want to go to school.

To my surprise, Lacchmi has made plans to pursue her dream. She will go, she says to a local anganwadi from 11-1 every morning. They will give her breakfast and Rs 10 for pocket money, daily. They will also teach her to read and write and sew. (I learned later that she was referring to a central government adolescent girls' scheme.)

I have not the heart to ask the twelve-year old if she has discussed her plans with her parents.

As the eldest daughter, Lacchmi is what the PROBE report would have described as a child mother. Providing crèche and childcare facilities is another of the purposes of the anganwadi Lacchmi longs to attend. A conveniently located facility with good outreach would solve the problems of a child like Lacchmi yet the coverage in Chingrajpara and elsewhere is shockingly inadequate.

The PROBE survey calculates the per child average annual cost of schooling to be as high as Rs 318. This may seem a negligible sum, but given the high variability of their hamaali earnings, there is no guarantee that Kiran and Devendra will have the money when their children demand it. The PROBE report also makes this point. For the slum's poorest families like Lacchmi's, these costs can be prohibitive especially with multiple children to send to school. Not surprisingly, in the eyes of the parents, the benefits of schooling for girls especially can be easily outweighed by the costs.

EARLIER

Yet the coverage is clearly far from adequate. In response to my question about the mid-day meal scheme at the Chingrajpara school, the teachers could only cite the lack of premises to prepare the food, the lack of staff (shiksha karmis) to prepare and serve the meals, the disruption of classroom learning and other bugbears. That this scheme has been successfully implemented elsewhere suggests the missing resource may in fact be systemic commitment.

As an alternative, a dry rations scheme is in operation each child is supposed in theory to receive a monthly ration of three kilo rice. But the rations are irregular and not sufficient incentive for Lacchmi's parents to ensure more than her mere enrolment.

Indeed it may appear that Lacchmi's predicament owes much to the specific circumstances of her family her status as eldest child, the lack of extended family support and most of all, her father's alcoholism. Yet, in all of these circumstances, Lacchmi is not unique they are widespread enough to keep 82 per cent of all women in the PROBE states illiterate at age 25. What Lacchmi needs is really an unwavering societal commitment to her chance at a better life a 'schooling revolution' of the kind the PROBE team found in Himachal Pradesh where it becomes a social norm for all children, male or female to be in school and be learning.

Postscript, December 2003: On my second visit to Bilaspur roughly 18 months later to collect data on the cycle-rickshaw rental market, education is a topic that erupts spontaneously in the focus groups of rickshaw-drivers. Each time, the poor, little-educated men gathered there offer to produce as guinea pig a child, in class fourth or fifth or sixth, who cannot write even his or her own name. The poor quality of their schools is a subject that clearly exercises these hard-working people.

I also see Lacchmi again. She has grown to be a bonafide beauty by now her mother is actively searching for a groom for her, says neighbour Geeta Sahu. But this time, Lacchmi also has another baby slung on her hip the youngest. The child mother smiles in recognition when I call her but shows no signs of her former inquisitiveness. "Did you go to school then?", I ask her about her dream of attending the anganwadi. She shakes her head and looks away, smiling shyly.

The other children gather for their evening game of hopscotch or what they call Falli, Gadda or Dandak. As they skip from square to square, Lacchmi is no longer one of them. She has outgrown play, and school.