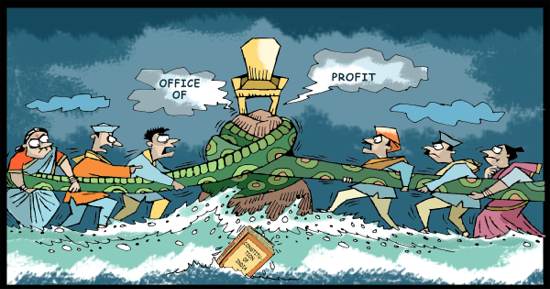

Member of Parliament (MP) Jaya Bachchan's disqualification, the proposed ordinance to save some MPs, the opposition's hue and cry that the ordinance was to save Sonia Gandhi -- President of Congress Party and leader of United Progressive Alliance comprising of non-rightist parties at the Centre, and her strategic resignation to disarm the opposition and neutralise the sting in their attack, all led to serious controversy over a number of government offices, their profits, and the control of the government over legislators in these offices. Jaya Bachchan was disqualified because she was also chairperson of the Uttar Pradesh Film Development Corporation, a statutory body.

•

Govt. proposes, Parliament..

•

Campaign for electoral reforms

Articles 102 and 191 of the Constitution were originally aimed at securing total independence to legislative members and that is why the holding of an 'office of profit under government' is prescribed as an operative disqualification. To deal with some emergency and complex situations, the articles provided for declaration of some posts as not office-of-profit under government by law. Section 3 of Parliament (Prevention of Disqualification) Act, 1959, declared some offices as not to disqualify their holders for membership of either House of Parliament. For instance: Offices held by Ministers, Chief Whip, Deputy Whip, chairpersons or members of temporary advisory committees, specified non-statutory bodies, etc. More positions were declared exempt by other legislations. State laws also have similar provisions.

The worry now -- and this is a legitimate one -- is that all political parties might agree to further dilute the principle of office of profit as a disqualification and permit a expanded list of exemptions to be added to Parliament Members (Removal of Disqualification) Act 1959. This is totally against the spirit of democratic constitutionalism, which thrives on strict separation of legislature and executive. The government is responsible and accountable to the legislature.

Farzana Cooper

In India, the line of separation is already very thin between executive and legislature. The executive emerges out of and confines to the legislature. The Council of Ministers decide legislative policy and run the House according to their needs, under the 'able' guidance of a 'speaker' who is part and parcel of the ruling political power base. All this, inspite of an Opposition's 'stock' opposition to almost every thing proposed by the central government. And though, for namesake, the power to move any bill is vested in each member as 'private member legislation', in practice, this happens very rarely. Many important legislations are not discussed and it would be difficult to find the 'quorum' needed for accepting the bill.

Disqualification based on office of profit is a democratic concept which has universal relevance in almost all democratic countries governed by a constitution. For instance, Article 35 of the U.S. Constitution mentions the phrase and defines it thus: "An office to which fees, a salary or other compensation is attached, is ordinarily an office of profit."

Every office of profit does not invite disqualification for a member of legislative house either at the Centre or States. It should be an office, of profit, and be 'under government'.

On the matter of fees, India's Parliamentary Members (Office of Profit) Amendment Act, 1959 was brought in to amend the Legislative Assembly Act 1867 and the Officials in Parliament Act 1896. "A member is not to be taken to be entitled to a fee or reward if the member irrevocably waives for all legal purposes the entitlement to the fee or reward," it says. It is clarified that 'fee or other reward' does not include "reasonable expenses actually incurred by or for the member for any one or more of the following -- accommodation; meals; domestic air travel; taxi fares or public transport charges; and motor vehicle hire."

The courts have already clarified

The three aspects -- 'office', 'of profit, and 'under government' -- came up for decision before apex court in case of Shibu Soren, the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha(S) leader (Shibu Soren v Dayanand Sahay AIR 2001 SC 2583). The Supreme Court set aside the election of Shibu Soren, to Rajya Sabha in June 1998, on the ground that he was holding "an office of profit" under the State Government as chairman of the Interim Jharkhand Area Autonomous Council (JAAC). The council was setup under the JAAC Act, 1994 at the time of his filing of his "nomination papers" and Soren was thus disqualified to contest election to Rajya Sabha. The expression 'under government' was also explained: "with regard to the "office of profit", what needed to be found was, if the amount received by the person concerned from the office he/she holds provides some pecuniary gain, other than the compensation to defray him/her out of pocket expenses."

The apex court held that Soren was was holding office "at the pleasure of the State Government". The court noted that the government had the right to remove or dismiss the holder of that office, besides controlling the manner of functioning of the Interim Council and providing funds for the Interim Council, out of which an honorarium of Rs.1750 per month, besides daily allowance, rent-free accommodation and a chauffeur driven car at the state expense, was paid to the appellant. The CJI further observed that all this "was a benefit capable of bringing about a conflict between the duty and interest of the appellant as a Member of Parliament - the precise vice to which Article 102 (1)(a) is attracted".

The right to appoint and remove the holder of office in many cases becomes an important and decisive test.

The apex court, in dismissing Soren's appeal against an earlier High Court verdict, said that "both Articles 102(1)(a) and Article 191(1)(a) of the Constitution were incorporated with a view to eliminate or in any event reduce the risk of conflict between duty and interest amongst Members of the Legislature so as to ensure that the concerned legislator does not come under an obligation of the Executive, on account of receiving pecuniary gain or profit from it, which may render him amenable to influence of the Executive, while discharging his obligations as a legislator."

Election Commission needs to do more

The Election Commission of India, after successfully recommending that the President to disqualify Samajwadi MP Jaya Bachchan, is now flooded with several complaints against sitting legislators for holding 'office of profit'. It has taken notice of petitions received against 10 CPI(M) MPs, including the Speaker, and others and in most of the cases it has sought more information from the petitions because "details were lacking". It is reported that the Election Commission has asked the petitioners including Mukul Roy of the Trinamool Congress to give details like the date of appointment of the MPs to the offices said to be held by them, along with documentary evidence to substantiate their contention that they were offices of profit.

Under current law, if a contesting candidate is already holding an office of profit under the control of the government, it is a disqualifying factor. If this factor is not noticed and the office holder wins the election, it is for the losing candidate to challenge the election before the High Court within one year. Before elections, it is the duty of the Election Commission and its officers to look into the nominations and study whether they hold any post which would disqualify them for contesting elections. Already, a 'regular' government employee cannot contest elections. The resignation, acceptance and due relieving orders are insisted upon as basic requirements to contest.

Post-election, if a legislator is appointed to an office of profit under government control, the complaint has to be given to the Election Commission which has jurisdiction to enquire and recommend steps to the President or Governor, who are bound by its recommendation.

The Election Commission must look in general into the office of profit itself as 'disqualification' during the nomination stage itself. Being a constitutionally prescribed disqualification that strikes at the root of validity of membership, election officials need to check whether a particular contestant holds any such office under government. It is also the duty of citizens in general and rivals in particular to bring such facts to the notice of returning officers.

The parties and their spiritless agenda

•

Govt. proposes, Parliament..

•

Campaign for electoral reforms

There's more. Any government, especially a coalition, is seen to be doing everything to retain legislators in their flock. Offering plum positions is one such method to silence their potential dissidence. Chairpersons of Public Sector Corporations and Statutory Bodies are not qualified to continue as members of legislative houses (e.g. Jaya Bachchan), and yet, governments have ignored these provisions.

The legal counsels of Sonia Gandhi say that her position as Chairperson of National Advisory Council (NAC) could be an office and office of profit, but definitely not "under the government" and hence she can not be disqualified. But the NAC position itself is of cabinet rank, which has several financial benefits and allowances from the government. It is true that the present government itself is under the influence of Sonia Gandhi, and hence it may be arguable that Sonia Gandhi as Chairperson of NAC is not under the influence of 'government'. Even if this were the case, it would be because of her unique position as the leader of the Congress Party.

However, any other person with the same rank would be definitely under the influential power of the government, which is objectionable under Article 102. Worse, if the law is amended and it is declared that positions such as NAC chairperson are not offices of profit, the spirit to make legislators independent, uninfluenced and unbiased, will be lost. Those who demanded disqualification of MPs for holding 'double' positions are eager to 'define' an 'office of profit' and 'declare' some offices of profit as not so. Over the years, each party has decorated their legislators with hundreds of positions in government when they were in power. The Congress, having run the country for several decades, naturally stands on the top in appending offices of profit to its own party legislators to keep the flock together or to nip dissidence in budding stage.

In the states, Uttar Pradesh and Jharkhand State Assemblies have passed amending legislations to exempt hundreds of posts from being considered as 'offices of profit" to avoid disqualification of legislative members. In Jharkhand, the bill saved its legislators and helped the coalition government, which is running with wafer thin majority, to survive. The Uttar Pradesh bill, though passed, could not come to the rescue of Jaya Bachchan, but would certainly help other leaders who are facing the threat of disqualification. The U.P. legislation exempted 79 positions.

Culmination of trends

The attempts of UPA Government at the center to achieve consensus and amend the law to facilitate some MPs to hold additional offices of profit, indicates the climax of the trend of the governments to dilute the spirit of the Constitution. If the Parliament passes a law carefully protecting all prominent members, every state will follow the suit and there will be spate of legislations in states totally circumventing the Articles 102 and 191. This will then be tantamount to eliminating the rule of double positions.

Removal of every disqualification is the basis of concentration of power. It appears that the purity and independence of legislative membership is the target of every political party so that their people enjoy more than one position without threat of 'disqualification'. All the political parties are generally in the same situation as the Congress and Samajvadi Party. Hence there is likely to be unprecedented unity and consensus among all the parties to protect their political interests of present and future. The political parties, which pounced upon Jaya Bachchan and Sonia Gandhi, have no moral status to reach an agreement to dilute this constitutional ideal.

The present controversy is just one facet of political corruption. On the matter of disclosure of candidate backgrounds to voters, all parties joined together to nullify the directions to Election Commission to insist on self declarations of criminal track record, financial and educational status. This was an example how all the vested political interests work together, cutting across political differences, to kill constitutionalism. It is happening again now as all 'left and right' parties are attempting remove any disqualification on office of profit grounds.

Citizens who argue for reforms and corruption-free-political-offices need to develop a comprehensive vision. While some talk about curtailing horse-trading use to hammer out a coalition from a hung house, others discuss the cleansing of legislatures by weeding out criminals. On the one hand, sting operations put a total full stop to the political career of bribe-taking MPs, and on the other, cabinet positions and corporation chairmen posts become the most offered allurements to switch the sides, in spite of a stricter anti-defection law.

The Parliament Members (Removal of Disqualification) 1959 needs no amendment. The expression 'office of profit' needs no definition as the judiciary has already explained the criteria where an office has to be termed as an office of profit under government. If at all it is amended, the expression should be given the meaning which is deliberated and concluded by the judgments. The list, which now exists under the 1959 law should not be expanded.