A large proportion of the Covid-19 cases during the second wave of the pandemic were in the rural areas of the country. Typically, these places lack adequate healthcare infrastructure, and were ravaged by the rapid spread of the virus. A rush of people from the rural areas headed to the cities for treatment, overwhelming the capacities of hospitals in the cities and towns too. That scenario could repeat in a third wave, if - or more likely, when - there is one. But are our cities more ready this time?

In Kerala, especially during the early months of the pandemic, it was observed that decentralised institutional mechanisms were the solution to handling the virus. Local, empowered action by panchayats as well as administrators in small towns was key to testing, tracing and treatment of those who were infected. Despite high numbers of infections, Kerala was able to keep fatalities to a relatively low percentage, compared to other states. Decentralised war-rooms of Mumbai were also seen as the successful model that other cities could emulate.

The importance of decentralisation was acknowledged in Karnataka too. In July 2020, the Urban Development Departments directed the Deputy Commissioners of all districts to set up Ward-Level Task Forces (WLTF) and Booth-Level Committees (BLCs) in all urban areas, big and small, to handle Covid-19 in a decentralised manner. Similarly, village and town task forces have been notified by the State government again in May this year. It's not known how many of these task forces are functional, but judging by the apparent facts there is still a lot more to be done for them to be effective.

Except for three official members, the other members of these Task Forces have not been officially nominated as per the criteria given in the notification. This has left it open for all and sundry - mostly political party workers of the party in power - to participate in these Task Forces, without official nomination. Since these are not statutory bodies, officials consider them expendable bodies, which can be formed or disbanded any time depending on the need or 'demand' for them, determined by the strength of the pandemic.

It is also intriguing that such temporary, expendable groups are being set up in these cities instead of formal Ward Committees, which are supposed to be performing the functions of such task forces. The Ward Committees are legally mandated, decentralised institutions as per the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act. But except in Bengaluru - and that too only intermittently - they have not been constituted anywhere in Karnataka even 29 years after the enactment of the Amendment in 1992. This is a gross violation of the Constitution for which no one has been held accountable so far.

It is also mandated by Rule 6(8) of Karnataka’s Ward Committee Rules of 23.06.2016 that every ward should have a Ward Disaster Management Cell (WDMC) under the formal ward committee to be "prepared for, respond to, recover from and mitigate" all kinds of disasters. Presumably, this includes a pandemic too, but as we see clearly the government has preferred an alternate route rather than what is already provided for in law.

Struggle to constitute Ward Committees and Area Sabhas

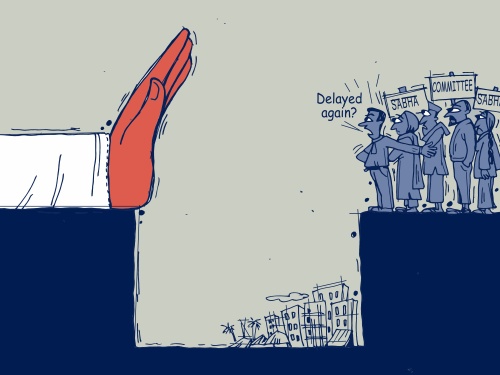

The formal Ward Committees were constituted after much delay in Bengaluru; this has been mostly achieved due to the High Court cracking the whip, as well as citizens and civil society groups exerting pressure on elected representatives and local government authorities. The most recent instances of judicial direction occurred in August 2019, when the High Court directed the Mangaluru Municipal Corporation to set up Ward Committees. And just a few days ago, it directed the Mysuru Municipal Corporation also to do the same. Recent citizens' activism and civil society demands in Mangaluru, Hubballi-Dharwad and Davangere have also broken new pathways, and are seeing some positive results.

Illustration by Farzana Cooper.

Illustration by Farzana Cooper.

Area Sabhas, which are similar to the Grama Sabhas in rural areas, are forums through which every urban voter could participate in the governance of his locality and are the means for bottom-up planning by citizens; these are also mandated in all municipal corporations in Karnataka through an Amendment to the Karnataka Municipal Corporations (KMC) Act in 2011. These too have remained unimplemented in entire Karnataka, including in Bengaluru, because the Urban Development Department (UDD) has failed to delineate 'Areas' for constituting the Area Sabhas, which is rightly seen by citizens as a delaying tactic.

The local Municipal Councils and Corporations themselves have been at fault, in most cases, because of the reluctance of councillors to share decision-making power with the people. In response to the UDD's circulars asking cities to constitute Ward Committees, the Mangaluru Municipal Corporation had set up a Sadana Samiti instead a few years ago, consisting of three councillors, to go into the question, "whether Ward Committees were needed at all in Mangaluru". But this is a Constitutional requirement! In Tumakuru, there were press reports that the Council had passed a resolution against forming ward committees, but this was refuted by some councillors later, saying that only a few members had said so and it had been wrongly minuted as a resolution of the whole Council.

Frustrated by the MCC's stalling techniques, the Mangaluru Civic Group which had been demanding the formation of Ward Committees for long, filed a PIL in the Karnataka High Court along with CIVIC and Nagarika Shakti in 2018. As a result of the PIL (WP 53244/2018), the Karnataka High Court ruled in August 2019 that 'Areas' for constituting the Area Sabhas should be notified by UDD immediately, and Ward Committees should be constituted immediately after the elections to the Mangaluru Municipal Corporation.

As any order of the High Court for any one city applies to other cities as well, UDD has asked all other municipal corporations where elections have been held - namely, Mysuru, Davangere, Shivamogga and Tumakuru - to also form Area Sabhas and Ward Committees. Despite these orders, ward committees have been set up only in Tumakuru so far and the process is still not complete even in Mangaluru, despite the specific orders of the HC regarding Mangaluru. Mysuru citizens then went to Court asking why Ward Committees have not been formed there yet despite the HC's earlier judgment, and as noted above they recently won a further verdict in their favour from the Court.

No uniform procedure for selecting members

Not only has it been difficult to get the Ward Committees formed in different cities, their functioning is also hampered by the manner in which they have been formed. A disconcerting feature of the Karnataka Municipal Corporations Act is that it requires Ward Committee members to be nominated by the Corporation. This language is vague - it is unclear whether 'Corporation' refers to the Councillors of each ward, or the administration - and has caused much consternation. In Bengaluru, councillors nominated their followers, relatives and others politically allied to them as Ward Committee members, defeating the very purpose of the Act.

But as a result of the HC judgement in the various cases, and due to awareness programmes being conducted in several cities by NGOs, including CIVIC, a number of citizens' groups have been activated in these cities. Knowing about the favouritism and nepotism that have crept into the nomination process of Ward Committee formation in BBMP, citizens in many of these cities have been demanding that their Commissioners should follow a more transparent and democratic procedure for the nominations of Ward Committee members.

As a result, the Hubballi-Dharwad Municipal Commissioner (HDMC) had written to the Directorate of Municipal Administration (DMA) in October 2019 seeking guidelines on the manner of nominating Ward Committee members. He wrote that the letter of the DMA of July 2019, "did not contain clear enough directions". But he does not seem to have got a reply; when an RTI application was filed by Nigel Albuquerque of MCC Civic Group asking for the said guidelines, the HDMC Commissioner admitted that he had not received any guidelines from UDD in response to his request.

Citizens have also been demanding that citizens' applications for Ward Committee membership should be called through public advertisements. Thus, Commissioners of Mangaluru, Hubballi-Dharwad and Davangere have issued public advertisements and received hundreds of applications from citizens. But in the absence of uniform guidelines from UDD, each Commissioner has been fixing his own criteria for membership and manner of nominating the citizens.

Thus, the Mangaluru Commissioner has asked applicant-citizens to file affidavits on stamp paper stating that they do not have any criminal cases against them and that they do not belong to any political party or have any "political affiliation that will bias their decisions". Mangaluru Civic Group have also convinced their Commissioner to set up a selection committee for finalising the names of ward committee members. The Davangere Commissioner asked only for Aadhar number, voter ID, ration card, etc. from those seeking to be on Ward Committees. It is not clear what procedure was followed by Tumakuru.

In contrast to these differences and confusion prevailing in the larger cities, it is interesting that the recent Amendment to the Karnataka Municipalities Act (Act 39 of 2020) - which applies to all cities other than the large municipal corporations - prescribes the criteria within the law itself for the selection of an Area Sabha Representative (ASR) who also automatically sits on the Ward Committee as a member. It eschews the nomination process and instead says that the ASR shall be chosen by the members of the Area Sabha, that is, by the voters themselves. As a result, voters in small cities have been given the privilege of selecting their ward committee members themselves, which is being denied to voters in bigger cities.

What does 'area' mean?

The other issue of concern pertains to the notifications being issued by UDD to define 'Areas'. For Mangaluru, which consists of 60 wards, UDD has notified 121 Areas splitting each ward into just two Areas. In Davangere, 45 wards have been notified to have 95 Areas. Each Area here will have from 4,000 to 6,000 voters. If the same principle of splitting each ward into two ‘Areas’ is followed for Bengaluru, each Area will have about 20,000 voters. It is obvious that such delineation of Areas will make the idea of having Area Sabhas unfeasible as no meaningful meeting can happen with 4000 or 20,000 voters.

|

Here too, the smaller towns seem to be at an advantage. The Karnataka Municipalities (Amdt.) Act of 2020 has defined every Polling Booth Area, which may have a maximum of 1000 to 1200 voters, as the Area for constituting Area Sabhas. This gives voters in these towns much greater say in their local affairs.

Conclusion

It is necessary to ensure that all cities constitute the long-overdue, formal ward committees, Area Sabhas and WDMCs under a uniformly applicable framework set within the law itself. They must also train and empower members of such committees to handle governance issues in their respective areas, and also be able to resiliently manage disasters in a decentralised way at the ward and booth levels. For this, an open democratic process is needed, without nepotism and favouritism, and enabling genuine citizen participation, which will not be beholden to the elected representative but hold him accountable to the community.