The literature that surrounds beauty pageants largely focuses upon the pageant as a space within which either popular culture (eg; Banet-Weiser 1999; Riverol 1992; Lovegrove 2002) or globalization (Cohen et al 1995) are critiqued. I contend that recognizing that standards of beauty must necessarily be negotiated by most women in the course of their lived experience would serve as a valuable contribution to understanding not only what pageants as a cultural phenomenon mean, but also as a means by which to gain a clearer picture of what gendered experience actually means in the whole spectrum of women's experience.

Young women enter the Miss India pageant fully expecting to change not only their bodies, but also to emerge several months later as fundamentally altered human beings. Under the gaze of the experts at the training programme and later, the judges, individual women try their best to present the qualities that Miss India as a concept is associated with; the qualities, in short, which ideally are to represent the pinnacle of its version of Indian womanhood at international pageants like Miss Universe and Miss World.

Young women enter the Miss India pageant fully expecting to change not only their bodies, but also to emerge several months later as fundamentally altered human beings.

The process of becoming Miss India begins every year in August or September, when Femina magazine prints entry forms in both its pages and in the pages of the group's flagship newspaper, the Times of India. Several thousand young women from all parts of the country submit the form along with photographs of themselves, one a full body shot and one a close-up of the face. Based on these photographs, a more limited number of young women are summoned to participate in the pageant if they fall within the parameters of being above 5'7'' in height and under 25 years of age.

Yet the concept of Miss India being exclusively urban is not a new one. Because of the enormous cultural divide that exists between urban and rural India, young women who do not live in big cities do not have the same kind of access to media images in terms of lifestyle that their urban counterparts do. As a result, according to Pradeep Guha, they do not have the kind of knowledge required to present themselves as beautiful on a global stage.

This symbolic capital is most often found in young women who come from backgrounds that have allowed them a great deal of independence. Many come from military families, whose constant mobility in terms of lifestyle places them as what Pradeep Guha described as "very secular, very cosmopolitan and very modern and outgoing." This is the kind of outlook, which is not based in regional identity, but in a more decentered concept of self, that is emblematic of what Miss India is today.

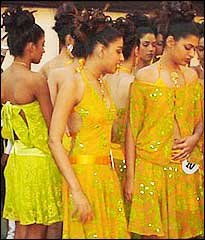

The Miss India pageant holds a thirty day training seminar in Bombay prior to the event itself. During the course of this one month, twenty-three contestants are housed, trained and made beautiful in what is an institution with one goal in mind: to create a Miss World or a Miss Universe. Every morning, for thirty days, Miss India contestants attend fitness classes twice a day and have all of their meals catered by well-known dietician Anjali Mukherjee. In fact, every aspect of the pageant employs the best-known people in the glamour industry to perform necessary services, thereby helping to construct an image of the pageant as larger than life. Having the opportunity to meet with the individuals who train them, all of whom are extremely well known throughout urban India, gives young women who compete in the pageant the chance to create a social network that will allow them to build careers in the glamour industry in India.

Young women who do not live in big cities according to Pradeep Guha do not have the kind of knowledge required to present themselves as beautiful on a global stage.

Ingredients of Miss World

As the 'recipe' above clearly illustrates, the contestant herself is discursively constructed as contributing rather little to the process of becoming Miss World. Rather, it is 'the experts' who do the majority of the work by sculpting her into the ideal of what Miss World should be. The initial ingredient, "a suburban Mumbaiite", followed as it is by the names of the experts, is a rather snide reference to the enormous class divide that exists between a young woman from the suburbs and the elite, South Bombay-dwelling experts.

The contestant herself is discursively constructed as contributing rather little to the process of becoming Miss World. Rather, it is 'the experts' who do the majority of the work by sculpting her into the ideal of what Miss World should be.

Mareesha's statement points to the way in which the training programme gives contestants the opportunity to create a social network that allows them to enter numerous fields in media. India is so incredibly socially stratified that building such a network would ordinarily otherwise be impossible for a young woman not from an elite background, although some contestants certainly do come from upper class families. Citing the benefits that simply participating in the training programme provides to young women, Mareesha underscores the way in which Miss India acts as a gateway to social mobility.

The culture of celebrity that positions those deemed the experts as authorities on everything from their actual field to what constitutes symbolic capital is largely the result of economic liberalization, which necessitated the development of a group of individuals who could translate between international trends and an urban Indian context. Positioned as cosmopolitan individuals of the highest caliber, the experts are treated with deference both at the pageant and in popular culture at large.

Experts who recreate

The panel of experts who comprised the 2003 training staff did not vary much from years past. Comprised of a list of celebrities and individuals well known in the field of media in Bombay, they are chosen to impart knowledge to the contestants as part of the gurukul system that Mr. Parigi envisions. These included a fashion designer, dermatologist, dietician, two hair stylists, a make up artist, a self-styled 'grooming expert', a personal trainer, a cosmetic dental surgeon, a spiritual guide, a diction coach, the head of an art foundation, and a photographer.

The contestants are consistently reminded of how they should behave with the experts, even by other experts themselves. As makeup artist Cory Walia explained to the contestants during a session, one must never presuppose that one has knowledge that the expert does not, even if it concerns oneself. "Do not tell the makeup artist what suits you" he insisted, "that person is a professional - you will end up in tears and you may even get a slap."

Positioning the threat of physical violence as a response to questioning the knowledge of the experts, Cory illustrates just how entrenched the culture of celebrity is entrenched in urban India. Once an individual has achieved a certain amount of social recognition for his or her work, they are perceived as being entitled to behave according to their whims. I often marveled at the contestants' ability to tolerate the sometimes downright insulting behaviour on the part of the experts. Had I been spoken to by anyone as some of the contestants were by the experts, I would have to been unable to avoid bursting into tears.

Over and again, I watched one organizer chastise the contestants for their behaviour. During the auditions for the 'Miss Talent' title, to be performed at the final pageant, she snapped at a contestant who, in her opinion, was giggling too much. "You're a Femina Miss India contestant now, and you need to behave like one! Be more ladylike." Archana's harsh tone made the contestant, who had been under an enormous amount of strain throughout the previous week of training, almost cry.

For one month, the contestants' lives are controlled and dictated by the experts. From skin care to diction to diet to spirituality, the training is designed to provide what Femina consistently describes as "a comprehensive crash course in life". Of course, the kind of life that the training programme cultivates is one that revolves around physical appearance. Although the body and diet were consistent points of attention, the most striking focus of the programme was on skin colour.

Only fair is lovely

I sat in on weekly individual sessions that dermatologist Dr. Jamuna Pai held with the contestants in order to examine their skin. Every single one of the young women was taking some sort of medication to alter her skin, particularly in colour, in the training programme in 2003. In a disturbingly casual manner, Dr. Pai emphasized the need for all the contestants to bleach their skin by prescribing the peeling agent Retin-A as well as glycolic acid and, in the case of isolated dark patches, a laser treatment.

Every single one of the young women was taking some sort of medication to alter her skin, particularly in colour, in the training programme.

"Fair skin is really an obsession with us, it's a fixation. Even with

the fairest of the fair, they feel they want to be fairer."

In the name of confidence, then, the contestants undergo chemical peels and daily medication, some of which have rather unpleasant side effects. Harsimrat, for example, often complained to the doctor that she felt nauseous and weak as a result of the medication prescribed to lighten her South Indian skin.

The contestants also received supplements in order to make their skin appear healthier. However, sometimes these did not work; in one contestant's case, Dr. Pai sighed and said "I'm giving you ten multivitamins, but you're still not glowing. I'm afraid that the only solution is to eat more." The notion of being "afraid" to tell a contestant to eat more, and that contestant actually looking concerned at the prospect of having to do so in order to make her skin healthier, points to a deeply flawed system of gender which positions women's bodies as never being beautiful enough.

The human machines

As part of the project of constructing the Miss India body, the contestants were given a diet designed by nutritionist Dr. Anjali Mukherjee, best known in Bombay for her weight loss centers and health food. Utilizing a combination of ayurveda and allopathy, Anjali's advised each young woman on how to eat to suit one's constitution. Interestingly, her description of the diet plan to contestants sounds much like the concept of the body as a machine.

Anjali's description of the diet plan to contestants sounds much like the concept of the body as a machine whose functioning can be improved under the guidance of the experts.

Anjali's use of a vehicular metaphor to describe the body is particularly apt in the case of the training programme. In her conception of diet, each young woman needs to improve the "machinery" of her body. Like Anjali's concept of the car, each contestant's body is envisioned as a machine whose functioning can be improved under the guidance of the experts.

The question of how thin is thin enough remained with me throughout the pageant. While most of the young women were already underweight in my estimation when they tried out for the pageant, only two of them, who were severely undernourished, were put on a diet which allowed them to gain weight during the training. Indeed, throughout the training, I watched two young women clearly struggle with eating disorders which no one attended to, although other contestants did mention them as problematic in terms of their eating patterns.

Perhaps aware of my consistent concern with what the contestants were eating, Anjali Mukherjee was quick to note that the contestants were being well nourished when I asked her how she defines ideal body weight. Although she noted that "ideal body weight has a range", she curiously defined that range in terms of how much weight the young women needed to lose, which ranged from four to twelve pounds. It is important, however, to note that there was one contestant who was put on a weight gain diet: Anjali deemed her fourteen pounds underweight when she entered the pageant.

While Anjali's diet plan helped in the project of creating the Miss India body, fitness expert Mickey Mehta focused on the realization of that body. A fitness trainer for twenty-one years, Mickey has had the longest association with the pageant of any of the experts. Every day, he led the contestants with an exercise regimen that began at seven am every morning. It involved mostly aerobic exercise, which allows the body to maintain a lithe form without building up muscle, which is not a part of the Miss India body.

A touch of spirituality

Unusually focused on the totality of being, Mickey takes a spiritual approach to fitness. Making use of an eclectic and syncretistic cocktail of different beliefs, he guides the contestants as whole persons, not just bodies.

"I take what I like from different religions - Dao, Tao, Zen, yoga - the focus is on holism. I don't believe in branded spirituality. I believe in oneness, everything is just one. When a person looks into the mirror and sees himself and not an illusion, they are deluded. The lotus is the illusion, mud is the reality. This has nothing to do with weight loss - a beautiful body is a body that is in proportion, not a thin body."

Although his charismatic mélange of spiritual beliefs is fascinating, and on one occasion I found myself listening to him for two hours without my noticing the time that had gone by, the fact remains that Mickey's job is to cultivate a body which is thin, rather than spiritually pure.

Weight loss ordeals

"No one gets up in the morning and does puja or namaaz ... first you look in the mirror and try to worship yourself."

"I think that some of them are too thin, but that's not me, that's the demands of the line of work that they're getting into after this…Some girls were so huge around the hips that they needed to lose weight; otherwise they would look out of place and probably spoil the show for the other girls."

As an actively involved participant from the very beginning of the pageant, I was very aware of the fact that there never were any young women who were, in Mickey's words, "huge around the hips". All of the young women who tried out for Miss India were of normal weight, and many of them had been underweight before they even came to the training programme.

As we walked around the grounds of the hotel where the contestants were getting ready to begin their exercise routine for the morning, Mehta pointed to Swetha, who went on to win the Miss India-Universe title, as an example of someone who had worked very hard. She was slumped against a pillar and clearly exhausted; Mehta congratulated her on the eight pounds she had lost in two weeks. She smiled and thanked him before dozing off again, trying to catch a bit more sleep before her morning run began.

Indeed, some of the young women seemed perpetually exhausted throughout the course of the training. This, of course, was compounded by the fact that most were trying to lose weight in order to better their chances of winning. With an inadequate diet and a schedule that demanded fifteen hours of active participation every day, it was never much of a surprise to see young women propped against chairs, their bodies physically exhausted by the effort of trying to be beautiful.

Yet this effort was highly rewarded, contextualized as it was within a rhetoric of achievement at the training. Mickey Mehta noted with pride that it was the young women who worked the hardest to lose weight who often went on to win: "The ones who keep working hard despite everything are the ones who win. I've seen many such girls. I worked the hardest with Diana Hayden, who lost almost fifteen kilos, and then there was Yukta Mookhey, who was so huge that people just wrote her off completely, but during the training she worked so hard she lost twelve kilos and then on her way to Miss World she lost more."

Mickey's association of losing extraordinarily amounts of weight in a very short period of time as a result of hard work is part of the interesting language of the beauty pageant. As young women 'work hard' to become underweight and use their 'confidence' to answer largely vapid questions, they subscribe to a vision of femininity that undervalues womanhood in general.

I saw how difficult it is to present views that seem to be the products of an independent, thinking woman, but are in fact platitudes...development of a certain accent as a class marker is discursively constructed as essential for success at international beauty pageants like Miss World.

"People can go paranoid about winning the crown.. The primary drive for them is to make it big, but after they meet me, they may think they should become nuns. Some of them don't like meditation, and they just meditate on winning the crown, but I tell them that spirituality with intent is not spirituality."

Like Mickey, every expert was very clear about the role he or she had to play in helping the contestants. Hair stylists Javed Habib and Samantha Kocchar noted that "our role is to prepare contestants for the future, because most of them are going into the glamour line, and this is essential for them, because sometimes they have to do their own hair and makeup." Kocchar, who started working in her mother Blossom's posh Delhi salon after she returned from a beauty school in Chicago in her early teens, was creative director for the Indo-American film Monsoon Wedding, while Habib is the most well known hair stylist in India.

Cultivating narcissism

While I made sure to attend most of the training sessions, those conducted by former flight attendant and 'grooming expert' Rukshana Eisa were by far the most interesting, as well as entertaining in a way which almost mocked the urban South Asian admiration of the foreign. In these sessions, she used the symbolic capital that being a flight attendant in India still commands as a way to teach the contestants etiquette. As a trainer for Delta Airlines, Rukshana flies to Paris three times a week, and also runs her own grooming school, called Image Incorporated.

The Many Don'ts

In a style characterized by a series of exhortations for proper behaviour which begin with 'you should' and 'you must never', she advised the contestants on how to conduct themselves. Rukshana was clear that her training was absolutely essential for the contestants: "This is important for the girls, because our own culture doesn't teach these things. They can take it or leave it, but after this they'll be able to sit with diplomats and heads of state and know what to do. That's important."

Although Rukshana's emphasis on teaching the contestants manners which are largely foreign to most urban Indians seemed comical at first, it began to take on a more serious tone as I watched young women struggle to remember the complexities of, for example, cutlery, which will be discussed later in this chapter. Equally important is the ability of the contestants to answer questions likely to be asked in the Miss India and other international pageants. For nearly three hours every day, the young women would sit in chairs around a ramp as choreographer Hemant Trivedi sat with a microphone at a table directly in front of the ramp. As they practiced answering questions that I had written for them as a consultant to the pageant, Trivedi advised them on how to improve their responses.When contestants were not able to answer quickly enough, he would note, "when you hesitated, it showed you were unsure, which also makes me unsure about your sincerity."

Faking intelligence

As contestants tried to answer questions about which person they most admired and what their views were on subjects as diverse as abortion and reincarnation in an apolitical, audience-pleasing manner, I saw how difficult it is to present views that seem to be the products of an independent, thinking woman, but are in fact platitudes. For example, Kauveri, a contestant who often answered questions exceptionally well, named Hillary Clinton as the woman she most admires, "because she's a paragon of love, power and strength even though she's had a disastrous personal life." By naming Clinton, who so clearly reaffirmed patriarchal values by staying married to her philandering husband, as a role model, Kauveri answered the question perfectly in the context of the pageant: she named a woman in a position of power as a result of her marriage, which is rather non-threatening, and a woman who has sacrificed in order to keep her marriage together. Trivedi was extremely happy with this answer, noting that "it's correct not to be specific about her problems."

To be specific about Clinton's problems, of course, would have brought an element of negativity to the stage that would not have been audience-friendly. Contestants were warned to monitor every part of their being as they answered the question posed to them, from their words to their posture to where they held their hands. When Trivedi warned the contestants not to position their hands in front of their bodies, "lest it look like you are holding your crotch" I marveled at how the young women could manage to think at all with the sheer amount of scrutiny surrounding their every action.

The very formation of their sentences, as well as their tone of voice, was also the subject of daily sessions for the contestants. Sabira Merchant is a diction coach who speaks with an accent that is the amalgamation of British inflections and American usage that is generally marked as elite in urban India. As it is elsewhere, accent is a major indicator of class in India, and the development of a certain accent as a class marker is discursively constructed as essential for success at international beauty pageants like Miss World.

In addition to the other experts, several past Miss India winners were called in to speak to contestants about how to win. These young women were accorded the greatest amount of attention by the contestants, and also often requested to pose for photographs with the past winners after they were done addressing the contestants. Positioned as the ultimate authorities on how to win, the contestants were absolutely absorbed by the advice of international pageant winners.

Miss World 1996 Yukta Mookhey served as a consultant throughout the pageant, and spent two hours advising the contestants on the amount of work they should put into both themselves and the pageant: "There is never enough - compare yourself to yourself and think 'I can do better than that'. Here you are, just 26, and there are 94 girls at an international pageant. Believe that you're better than the best." Positioned as the ultimate role model for the contestants, Yukta was clear that the competition would become even tougher at the international level. The rhetoric of achievement and work evinced by Yukta ran through the entire pageant; young women were consistently and implicitly advised, whether in the form of medication to lighten their skin, exercise to make them thinner, or classes to lessen their Indian-accented speech, that they were simply not good enough.

Objectification of women

I contend that such rhetoric allows for the masking of the pageant's absolute objectification of women, and is therefore necessary. After all, if everyone consistently contends that the empowerment of women is its ultimate goal, this message becomes accepted as fact. The participation of experts, who are enshrined in urban popular culture as the demi-gods of post-liberalization Indian, only serves to further legitimize this project.

Being beautiful comes to be defined as a condition of being excessively thin, fair and tall, and no one can have any of these three qualities in excess at Miss India.

Although Hindi films are normally the next step for Miss India contestants, director Karan Johar, who completed the enormously successful Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham when he was just twenty-six years old, advised contestants that films were not the only option for them. "I don't know how many of you want to be actresses, but if you want to act, please act! Now there are about three hundred other platforms out there. I feel sad when I see so many beautiful faces and they all want to be actresses - it hurts me that they just want to do it for the money and recognition. You should want to do it for the art. I know that most of our actresses cannot be models, but models cannot be actresses."

In making a dividing line between different career options, Johar expressed the clear difference between being a glamorous figure and being an actress. In a film industry in which women are often decorative objects, Johar's exhortation to the contestants to 'please act!' was interesting, as it pointed to the way in which options in media have increased exponentially since liberalization.

Miss India training serves as a site in which young women are able to decide their future, or at least expand their options in terms of media-related careers. However, the training is extremely emotionally taxing, as it involves a rigorous fifteen hour schedule each day as well as the constant, unrelenting supervision of each young woman's behaviour.

Politics of Miss India training

"Remember, the moment you're out of this hotel, you're onstage

twenty-four hours": Hemant Trivedi to contestants.

Eerily resembling Foucault's concept of the Panopticon, which refers to a process by which individuals are so closely observed that they begin to monitor their own behaviour in much the same way that broader social institutions do, Trivedi's comment exhorts contestants to always monitor themselves, even when the experts are unable to do it themselves. As emblematic of the Foucauldian total institution, the Miss India training programme completely takes over the lives of the contestants for a month, placing them under the gaze of experts who are discursively constructed as able to transform the young women into glamorous icons which fit the ever-exalted 'international standards'.

As a concept, Miss India is gender inequality writ unabashedly large. The contestants are watched every minute by chaperones, some of whom are their age or younger, who make sure that they eat, sleep and do what they are told. Although I never witnessed a confrontation between a contestant and a chaperone, I was constantly aware of the pressure of being always watched. One chaperone mentioned the responsibility of making sure the contestants follow the regimen assigned to them:

Put in the odd position of supervising grown women, the chaperone's complaint points to the way in which contestants are always being observed. Yet, the contestants also observe themselves and each other, thereby internalizing the process of monitoring. The very fact that all meals were eaten as a group, where consumption could be watched by all, was in itself part of this.

As I sat with the young women over breakfast one morning, they entered into a complex discussion of the diets assigned to them by the dietician. One girl noted "I've lost two hundred grams, that's it. I'm 61 and a half kilos right now, and I want to be 60. She says I can't have fruit today, because it's fattening." Another commiserated that she had been assigned bread and eggs for breakfast, followed by two days of cucumber and chutney. As part of the odd speculations that are inherent in playing the diet game, the girls decided that fruit does not actually fall into the category of fattening, because "it's more of a maintenance food".

Fear of eating

The disturbing intensity with which the young women discussed their consumption patterns points to the way in which the total institution of the training programme enforces a kind of self-monitoring. However, the monitoring of contestants' consumption of food also extended to outright policing at times. When the young women were taken to the Amby Valley to meet the press, their first time outside of the hotel in a month, a pageant organizer warned, "there will be normal food there, but control yourselves. I don't want to have to come up to you and ask you to stop eating."

The politics of eating were the subject of much discussion throughout the training period. Contestants ate every meal from a buffet table on which three large tureens of food were arranged for them. For breakfast, they had cereal or fruit as an option, while for lunch they had two vegetables and soup, and for dinner they had rice and a protein-based dish. From these selections, contestants were expected to pick out what they had been assigned to eat by Anjali Mukherjee.

Contestants need to act sexy, yet non-threatening, and also calm, but still in control.

Being beautiful comes to be defined as a condition of being excessively thin, fair and tall, and no one can have any of these three qualities in excess at Miss India. This closely corresponds to Foucault's concept of how the Panopticon works to force prisoners to begin monitoring themselves. Indeed, Foucault defines power as embodied in "the strategies…whose general design or institutional crystallization is embodied… in the various social hegemonies" (1961: 93). As such, Miss India serves not only to reinforce standards of beauty for the contestants, but for the urban population who consume images of the pageant as well.

Even the allotted one hour visits from family members, held between nine and ten p.m. every night in the hotel's coffee shop, were supervised by chaperones. The coffee shop was rather conspicuously placed in the center of the hotel, which all twenty-four floors of the hallways looked down upon. This made it impossible for the contestants to express any emotions with family members that they may have felt uncomfortable expressing in front of others. One chaperone explained the rationale behind this policy as "because the reputation of the pageant is at stake, and we can't have ugly rumors cropping up." As a result, she argued, it was necessary for the contestants to be in full view with chaperones at all times.

Living in cocoons

When I questioned organizers as to why the contestants were not allowed outside of the hotel during their limited amount of free time, a chaperone stressed the fact that the outside world is, in a matter of speaking, not ready for the kind of young women that are contestants in Miss India: "The other day when we took them shopping we had to push them onto the bus because all the janta (crowd, in a negative sense) was gathering to stare at them. In India, women can't wear short things and those things all the girls wear make all the kachra log (literally, 'garbage people') stare at them. That's why we have to keep them in the hotel all the time."

Yet the phenomenon of being watched is also complemented by the power of being looked at. In most parts of South Asia, staring is not rude; in fact, it is common. If someone is different, others will let that person know it by looking at him or her. The notion of 'darshan', or the holy gaze, is deeply rooted in Hindu tradition, and other concepts, such as 'boori nazar', or the evil eye, are imports from Central Asian cultural contact long predating the British colonial period.

Being on constant display

Being looked at, then, is a form of power. One contestant laughed as she described how her servants "just love" watching her in her thong underwear, which she named as her garment of choice when she is at home. While this may be out of sheer disbelief about the practicality of such a garment from a servant's perspective, the opportunity to be gazed at is a coveted one in Bombay and Delhi. Page Three of the Bombay Times (or, in Delhi, the Delhi Times), a supplement of the Times of India, visually chronicles the nightlife of celebrities and is avidly consumed by a middle class readership.

Although beauty pageants such as Miss India are certainly instruments of male domination at a macro level, they can also be spaces of relative female empowerment and social mobility.

Shonal's assertion that she would "never be able to relax" points to the kind of constant public scrutiny that the contestants are subjected to, and how it increases tenfold if they win. When she insists that "people watch you more and more", the metaphor of the Panopticon, as well as the two-sided compliment of the gaze become especially clear given her matter-of-factness: being watched, it seems, is simply a part of life as a beauty queen.

Indeed, numerous sessions at the training programme were designed to prepare the contestants to be watched. For several hours one afternoon, diction expert Sabira Merchant led the contestants through an exercise designed to prepare them to be on television, perhaps the ultimate instrument of the gaze. One by one, each contestant came to the podium, where Sabira advised them that: "Everyone is watching you. Hold the mike level to your chest, make sure it's an extension of yourself. You'll sound sexy that way, well-modulated. You've got to sex up the audience, let's be honest. Everyone will be watching you, so be breezy, happy and in control, cool. "

Route to upward mobility

In a few brief sentences, Sabira sums up the need for contestants to act sexy, yet non-threatening, and also calm, but still in control. The more I learned about how difficult it is to present oneself as a beauty queen, the more I realized that it is incredibly sad that, like most things feminine, women's work in the space of the pageant is so profoundly devalued. However, given the chance to be looked at via the opportunities made possible by the training programme, the strain of being observed may very well be seen as worth the effort by many young women.

Throughout the training, contestants learned how to cultivate themselves in such a way that they fit into norms surrounding gender, class and beauty. What they were doing, in short, was forming relationships both with themselves and positioning those brand new selves in the world simultaneously. As representatives of what is discursively constructed by many urban Indians as a brand new, post-liberalization India, Miss India contestants, quite literally, serve as embodiments of the nation.

Indeed, what is lacking in the discourse of contemporary feminist approaches is an understanding of the way in which women negotiate a gendered universe in order to meet their own needs. Although beauty pageants such as Miss India are certainly instruments of male domination at a macro level, they can also be spaces of relative female empowerment and social mobility. As such, it is useful to examine the Miss India pageant with a view informed by an understanding of a real world feminism which pays as much attention to individual women's motivations for participating in patriarchy as it does to the flawed institutions that patriarchy perpetuates.

While it is self-evident that women are embodied subjects (Butler 1993), there is a dearth of literature that addresses how women successfully navigate the space of the body in order to achieve a version of femininity which is discursively constructed as beautiful. It is dangerous to label such women as mere victims of male domination, as to do so serves to deny them agency, as well as the intelligence to negotiate their social worlds.

Susan Runkle

Susan Runkle is a Ph.D. candidate in Cultural Anthropology at Syracuse University.

This work is based on more than a year of intensive research into the nascent beauty industry in South Asia. This article is based upon her participant observation as an academic researcher and unpaid consultant at the Miss India pageant's six week intensive training program for contestants.

References

![]() Manufacturing beauties

Manufacturing beauties

The Miss India pageant has emerged as a site for the creation of a new kind of woman in post-liberalization India. Under the guidance of leaders

of the Indian fashion, film and beauty industries, Miss India contestants learn how to construct gendered identities.

Susan Runkle

notes India's integration into the global beauty industry.

Throughout my presence at the 2003 Miss India training as an anthropologist conducting research as well as assisting in simple tasks such as writing questions for contestants, I was consistently struck by similarities between the creation of beauty queens and theories of the body that stem from the Industrial Revolution. Perhaps there has never been a more apt example of thinking of the body as a machine with parts to be repaired and replaced. Emblematic of gender as performance (Butler 1994), the construction of twenty-six potential Miss Indias from a group of relatively ordinary young women points to ways in which the body is what scholars such as Davis (1995) have called "cultural plastic."

![]() Following economic liberalization in 1991, the Miss India pageant grew from an event that originally showcased Indian textiles into a full-fledged media extravaganza. The most notable post-liberalization change in both the magazine and the Miss India pageant has been a shift from a focus on national identity to a focus on individual identity. Current Femina editor Sathya Saran was quick to describe the Miss India pageant as a tool with which to promote the magazine and also to, as she put it, "launch young women into life." Indeed, it was only after liberalization that the three winners were chosen each year in the Miss India pageant, titled Miss India-World, Miss India-Universe, and Miss India-Asia Pacific, were groomed specifically for each pageant. Each title winner then goes on to compete in the international pageant that her Miss India title decides for her, with Miss Universe being the most prestigious.

Following economic liberalization in 1991, the Miss India pageant grew from an event that originally showcased Indian textiles into a full-fledged media extravaganza. The most notable post-liberalization change in both the magazine and the Miss India pageant has been a shift from a focus on national identity to a focus on individual identity. Current Femina editor Sathya Saran was quick to describe the Miss India pageant as a tool with which to promote the magazine and also to, as she put it, "launch young women into life." Indeed, it was only after liberalization that the three winners were chosen each year in the Miss India pageant, titled Miss India-World, Miss India-Universe, and Miss India-Asia Pacific, were groomed specifically for each pageant. Each title winner then goes on to compete in the international pageant that her Miss India title decides for her, with Miss Universe being the most prestigious.

![]() Pradeep Guha, the publisher of Femina and manager of the pageant, then conducts a tour of major urban areas in India during which he personally meets with every aspiring contestant in order to select the young women who will comprise the final twenty-three that compete for the Miss India crown. Interestingly, however, as he described his annual search to me in the course of an interview, he was adamant that as he meets with young women in the urban centers that Femina chooses each year, he is not simply looking for a Miss India, but for a Miss Universe or a Miss World.

Pradeep Guha, the publisher of Femina and manager of the pageant, then conducts a tour of major urban areas in India during which he personally meets with every aspiring contestant in order to select the young women who will comprise the final twenty-three that compete for the Miss India crown. Interestingly, however, as he described his annual search to me in the course of an interview, he was adamant that as he meets with young women in the urban centers that Femina chooses each year, he is not simply looking for a Miss India, but for a Miss Universe or a Miss World.

![]() Beyond fitness and diet regimens, however, the month-long seminar also includes a heavy focus on the worlds of modeling, fashion and cinema. As these are the fields into which most Miss India contestants go after the pageant is over, it is only appropriate that the seminar is weighted in this direction. As such, simply being able to make it into the pageant itself can serve as a life changing experience for many young women, who compete with one another in a process, undertaken by experts in the Indian fashion, film and beauty industries, which Pradeep Guha referred to as "chiseling".

Beyond fitness and diet regimens, however, the month-long seminar also includes a heavy focus on the worlds of modeling, fashion and cinema. As these are the fields into which most Miss India contestants go after the pageant is over, it is only appropriate that the seminar is weighted in this direction. As such, simply being able to make it into the pageant itself can serve as a life changing experience for many young women, who compete with one another in a process, undertaken by experts in the Indian fashion, film and beauty industries, which Pradeep Guha referred to as "chiseling".

![]() However, it is precisely this class difference that allows for social mobility on the part of the Miss India contestants at the pageant. As Mareesha, a 2003 contestant, noted, "even if you don't win, you gain something, so it's not a wasted effort. You make so many contacts, by the end of it you have fifteen different options - serials, ramp, whatever."

However, it is precisely this class difference that allows for social mobility on the part of the Miss India contestants at the pageant. As Mareesha, a 2003 contestant, noted, "even if you don't win, you gain something, so it's not a wasted effort. You make so many contacts, by the end of it you have fifteen different options - serials, ramp, whatever."

![]() Being an expert brings with it a variety of privileges and responsibilities, the most striking of which is the right to be exceedingly rude without cause. One fashion designer, who designs the clothing the contestants wear at the pageant, is an excellent example of this. A choreographer and designer had to warn the contestants to be exceedingly polite to her, noting: "She may not be the warmest person in the world, but that does not mean you give her any bad vibes. Be gracious, as she is our most senior and respected designer." As an expert, all those who are not experts are expected to defer to her temperament.

Being an expert brings with it a variety of privileges and responsibilities, the most striking of which is the right to be exceedingly rude without cause. One fashion designer, who designs the clothing the contestants wear at the pageant, is an excellent example of this. A choreographer and designer had to warn the contestants to be exceedingly polite to her, noting: "She may not be the warmest person in the world, but that does not mean you give her any bad vibes. Be gracious, as she is our most senior and respected designer." As an expert, all those who are not experts are expected to defer to her temperament.

![]() When I asked Dr. Pai, who trained as a plastic surgeon in London, why fair skin was such a concern at the pageant, she offered the following explanation. "Fair skin is really an obsession with us, it's a fixation. Even with the fairest of the fair, they feel they want to be fairer. It isn't important anymore, because the international winners are getting darker and darker.You wouldn't notice our obsession, because you have such beautiful white skin, but I feel it's ingrained in us. When an Indian man looks for a bride, he wants one who is tall, fair and slim, and fairer people always get jobs first. Today, this is being disproved because of the success internationally of dark-skinned models, but we still lighten their skin here because it gives the girls extra confidence when they go abroad."

When I asked Dr. Pai, who trained as a plastic surgeon in London, why fair skin was such a concern at the pageant, she offered the following explanation. "Fair skin is really an obsession with us, it's a fixation. Even with the fairest of the fair, they feel they want to be fairer. It isn't important anymore, because the international winners are getting darker and darker.You wouldn't notice our obsession, because you have such beautiful white skin, but I feel it's ingrained in us. When an Indian man looks for a bride, he wants one who is tall, fair and slim, and fairer people always get jobs first. Today, this is being disproved because of the success internationally of dark-skinned models, but we still lighten their skin here because it gives the girls extra confidence when they go abroad."

![]() "The blood becomes purer and cleaner with the diet that we're giving, and your machinery is working better with it. The body is like a car that needs servicing, it's that simple."

"The blood becomes purer and cleaner with the diet that we're giving, and your machinery is working better with it. The body is like a car that needs servicing, it's that simple."

![]() When I questioned him further about his views of the kind of body he was being asked to help engineer for the contestants, he confessed that this body was a prerequisite for the world of media. As the following passage illustrates, Mickey conceptualizes of thinness as something of a necessary evil.

When I questioned him further about his views of the kind of body he was being asked to help engineer for the contestants, he confessed that this body was a prerequisite for the world of media. As the following passage illustrates, Mickey conceptualizes of thinness as something of a necessary evil.

![]() However, Mickey softens the obvious imperative to lose weight with his use of spirituality. He was insistent that "we are not looking at FTV here, we are looking at women who will make changes and be positive." Referencing the Fashion TV channel, which broadcasts twenty-four hour images of fashion shows around the world, Mickey constructs the training programme as set apart from the purely superficial world of modeling. In the following passage, he describes why it is important to cultivate one's spirituality in order to do well at the pageant.

However, Mickey softens the obvious imperative to lose weight with his use of spirituality. He was insistent that "we are not looking at FTV here, we are looking at women who will make changes and be positive." Referencing the Fashion TV channel, which broadcasts twenty-four hour images of fashion shows around the world, Mickey constructs the training programme as set apart from the purely superficial world of modeling. In the following passage, he describes why it is important to cultivate one's spirituality in order to do well at the pageant.

![]() Both Kocchar and Habib were clear that beauty is serious business. "No one gets up in the morning and does puja or namaaz," Habib noted, "first you look in the mirror and try to worship yourself." Habib's equation of the cultivation of beauty with religious experience is particularly apt in this case. Involved in the pageant for the first time this year, Samantha is the spokesperson for Sunsilk shampoo, while Javed endorses hair colour from L'Oreal.

Both Kocchar and Habib were clear that beauty is serious business. "No one gets up in the morning and does puja or namaaz," Habib noted, "first you look in the mirror and try to worship yourself." Habib's equation of the cultivation of beauty with religious experience is particularly apt in this case. Involved in the pageant for the first time this year, Samantha is the spokesperson for Sunsilk shampoo, while Javed endorses hair colour from L'Oreal.

![]() Although they were advised on how to improve themselves at all times in order to better their chances at winning, the rhetoric of never being good enough was further entrenched by the obvious reality that only three young women would win in the final pageant. As such, while the main focus of the experts was obviously to prepare and advise contestants on how to win an international pageant, several sessions were also conducted on career-related subjects. In this way, even the young women who did not win were provided with a social network which would enable them to enter media-related fields.

Although they were advised on how to improve themselves at all times in order to better their chances at winning, the rhetoric of never being good enough was further entrenched by the obvious reality that only three young women would win in the final pageant. As such, while the main focus of the experts was obviously to prepare and advise contestants on how to win an international pageant, several sessions were also conducted on career-related subjects. In this way, even the young women who did not win were provided with a social network which would enable them to enter media-related fields.

![]() Every week they get a new diet assigned in a private consultation with Anjali. I have to make sure they stick with it. One girl is seven kilos underweight, so she's on a weight gain diet, and she can eat pastries and cake in front of everyone, which bothers them.

Every week they get a new diet assigned in a private consultation with Anjali. I have to make sure they stick with it. One girl is seven kilos underweight, so she's on a weight gain diet, and she can eat pastries and cake in front of everyone, which bothers them.

![]() The fear of overconsumption, as well as the pressures of being watched while eating in front of the competition, in effect, served to make it painfully clear to the contestants that the standards of beauty were dependent upon both their self-control and their attention to expert advice. Although some young women worked harder than others at doing this (and some excessively so), the message of having to struggle to be beautiful was a constant at the training.

The fear of overconsumption, as well as the pressures of being watched while eating in front of the competition, in effect, served to make it painfully clear to the contestants that the standards of beauty were dependent upon both their self-control and their attention to expert advice. Although some young women worked harder than others at doing this (and some excessively so), the message of having to struggle to be beautiful was a constant at the training.

![]() Utilizing a rhetoric of protection, the chaperone underscores the sharp division between the world of Miss India and the reality that is India. While the contestants were free to roam around the hotel in varying degrees of undress without attracting much attention, the average man on the street would not be able to take his eyes off a glamorous woman in a mini skirt, simply because it is something that he would usually see only on TV, as he is unable to frequent the kind of spaces in which this sort of dress is common.

Utilizing a rhetoric of protection, the chaperone underscores the sharp division between the world of Miss India and the reality that is India. While the contestants were free to roam around the hotel in varying degrees of undress without attracting much attention, the average man on the street would not be able to take his eyes off a glamorous woman in a mini skirt, simply because it is something that he would usually see only on TV, as he is unable to frequent the kind of spaces in which this sort of dress is common.

![]() Shonal, a successful model in her native Calcutta before she was selected for the training programme, noted that doing well in Calcutta and at Miss India were two completely different things. "I'll lose my privacy if I win. In Calcutta, people know me, and there I have to be cautious about what I say and do. But as Miss India, I'll never be able to relax. Here, they turn you into a complete lady, but when people watch you more and more, your concept of individuality just goes."

Shonal, a successful model in her native Calcutta before she was selected for the training programme, noted that doing well in Calcutta and at Miss India were two completely different things. "I'll lose my privacy if I win. In Calcutta, people know me, and there I have to be cautious about what I say and do. But as Miss India, I'll never be able to relax. Here, they turn you into a complete lady, but when people watch you more and more, your concept of individuality just goes."

Manushi, Issue 143

(published September 2004 in India Together)

- Feedback: Tell us what you think of this article