In a recent article on India Together, Arvind Verma, a former IPS officer, now a US-based scholar, has ably and cogently examined the issue of police reforms in India today together with his recommendations. Based on years of study and research, he makes an irrefutable case for the necessity of police reforms.

The Prime Minister and his advisers, responsible for the recent setting up of the Police Act Drafting Committee (PADC), led by Soli Sorabji, should be happy to read Verma's paper, which views the issue from a rare international perspective. Verma has made an important contribution to the debate on police reforms. As a retired police officer who had been part of the system in India for long, I am interested in contributing to this debate.

Committee's terms of reference too narrow

Several issues arise. What is significance of the present designation of the PADC, which seems to restrict the scope of the needed police reforms in India to the drafting of a new Police Act as if this in itself would automatically also address the host of ills that afflict the Indian police system? What about the range of other issues that were painstakingly gone into by the first ever National Police Commission (NPC) in independent India whose uncared for recommendations (1979-81) lie buried in the dark caverns of the Union Home Ministry?

(The Police Act Drafting Committee completed its 6 month term limit on 31 January 2006.)

The restrictive TOR for the PADC appear to have been drawn up by someone who lacks understanding of the real challenges before the Indian police. The growth of insurgency, militancy and naxalism is attributable to failure of the state to provide humane development, social justice, and governance as understood in many UN and other similar reports. In civilized societies, the police are seen as an agency for the provision of human security, protection and service to the people in addition to maintaining order. Order maintenance, however, appears to enjoy top priority in India. Police-dominated intelligence agencies, which carry out conflict analysis for the government on issues such as insurgency, militancy and naxalism and dictate government policy, have historically adopted a catchall definition of 'national security'. This limits the usefulness of such agencies for optimum policy making.

The PADC follows earlier exercises such as the Prakash Singh public interest petition before the Supreme Court of India, the Julio Ribeiro Committee report, the Padhmanabiah Committee report and the recommendations of the National Human Rights Commission on the criminal justice front, not to mention the failed efforts of the then Union Home Minister Indrajit Gupta to implement the main recommendations of the NPC in 1997. Moreover, a fully revised new Police Act was also provided in the voluminous report of the National Police Commission (NPC) of 1979-81. In what respects has that exercise been found deficient?

Farzana Cooper

Further, in the recent period, India has witnessed some of the worst communal violence since independence resulting in the total collapse of the criminal justice system and of justice delivery in large parts of the country. The Gujarat carnage of 2002 witnessed the active participation and facilitation by the police in the unprecedented mass violence directed against the minority community. The criminal justice failures and violations on the part of the Gujarat police during the carnage are well documented in the three-volume report of the Concerned Citizens' Tribunal on Gujarat, led by Justice V R Krishna Iyer, titled "Crime Against Humanity" brought out by the Citizens for Peace and Justice, Mumbai.

The government of India has recently formulated a new law to contain communal violence of the type witnessed in Gujarat. While this does provide evidence of seriousness on the part of the current government in dealing with the problem in a way not provided for in the existing law, this law does not provide for the enforcement of 'command responsibility', which was a key issue in the Gujarat carnage of 2002. Command responsibility is that of officials in 'command positions' -- higher levels in the bureaucracy and the political executive -- not just those actually involved in dealing with the law and order situation on the ground. This includes the Commissioner of Police, Director General of Police, Chief Secretary, Chief Minister, Home Secretary, Home Minister, etc. And in the absence of far-reaching police reforms from a human rights perspective, the law may remain toothless in dealing with state-sponsored communal terrorism of the type witnessed in Gujarat, which may well repeat itself in future.

Gravity of the crisis

The TOR for the PADC thus does not adequately reflect the seriousness of the organizational crisis, which afflicts the police system today. This is a crisis which stems from its historical antecedents in the Irish colonial police structure on which it is modeled. The Irish colonial police was a paramilitary agency accountable only to the government. Its chief officer was called inspector general who reported to the chief secretary. The 'political-organizational' characteristics of the inherited Indian police structure includes strict subordination to the civilian administration, unaccountability to the public, coercive strength and disposition and frequent use of state violence, institutionalisation of an armed police within the civilian wing, an 'eyes and ears' function on behalf of the government, pervasive secrecy and close identification with propertied interests. These characteristics are not sustainable in a democratic, republican India and must be got rid of.

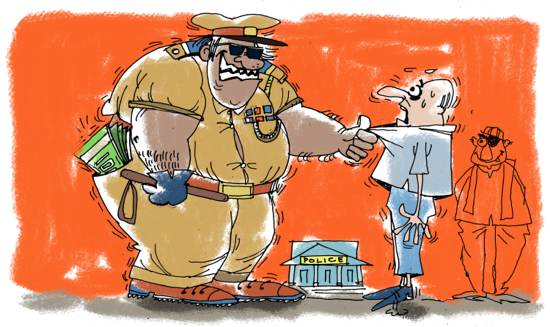

The basic philosophy of the Indian police today is elucidated in the Police Act of 1861. Its primary focus is to contain trouble after it occurs, whether mob violence or individual criminality. It is reactive in dealing with situations except when it is influenced by 'extraneous' factors. The contact between policemen and the citizens mainly involve actual or implied enforcement of law; non-enforcement mediation, not involving criminal sanctions, does not often take place. The requirements of maintaining public order and the collection of internal political intelligence have become the basic thrusts of the Indian police. The massive growth of centralized paramilitary police forces and the increasing strength of the intelligence apparatus since independence represent distorted patterns and priorities.

Thus, the challenges on the criminal justice front are not confined to the drafting of a new Police Act, important as it is. A whole range of deeper issues cry out for consideration. These need to be taken into account in the TOR of a reconstituted and renamed Committee with revised terms of reference, which, to carry conviction, must include eminent human rights activists both men and women, members of the Scheduled castes and Tribes, minorities, former Judges of the Supreme Court and activists on the Panchayati Raj front and experts from the northeast, all combined in a compact team. A new Police Act could well become the second most important official policy document after the Constitution of India, and it must be drafted carefully and well!

Consultations held, missed depth

The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) has been active in campaigning for police reforms in India and has organized many discussions across the country. CHRI held a one-day 'national consultation' in New Delhi, which I attended, to consider 'what must go into creating the police that we want for our country.' A large number of police officers from across the country were in attendance, though, sadly enough, one did not notice any established human rights activist, man or woman. The PADC was notionally represented by its secretary. Persons who chaired sessions and participated included former governors Ved Marwah and A P Mukherji (both former IPS officers) as well as journalist B G Verghese, and K S Dhillon (IPS Retd.), both associated with CHRI.

The disparity in human quality between the bottom and top ranks of the police hierarchy in India is striking and it reflects the disparity in the larger society.