Maitreyee Chatterjee is easily one of the best and most forthright journalists West Bengal has ever produced. With her passing on 17 January this year, the print media has lost a genuine, fearless and honest activist whose contribution to the women's movement is beyond compare. Her countless readers spanning two generations will miss her byline in dozens of print media outlets in English and Bengali.

She had equal command over both languages, and that gave her an edge over those who could only write in one. Maitreyee-di was also a rare combination of activist and journalist; no one can say with any degree of certainty which mattered more to her . the journalism or the activism. The lines between these two are quite blurred when one looks back on her volume of investigative stories based on extensive field work, interviews, and presentations at conferences and seminars across the country.

Maitreyee-di's marriage to Kishore Chatterjee, who she met at an ad agency when they both worked there, (he passed away six months before she did), lasted a solid four-and-a-half decades. He was one of the most eminent scholars and critics in India of Western classical music, and also a singer and an artist. His reticence and moodiness was matched by her tremendous energy and friendliness - despite the fact that she was physically weak having been born with a hole in her heart.

The Chatterjee house at Old Ballygunge Road kept an open door, with people walking in and out either to hone their tuning in Western classical music from Kishore or to request help from Maitreyee. They had no children. But Maitreyee-di has left behind hundreds of women who consider her their adoptive mother, who have received help from her in every which way, and have had their llives shaped by her. She stood stolidly behind marginalised girls and women, and some of them were also offered temporary shelter in her home till she found a better abode for them.

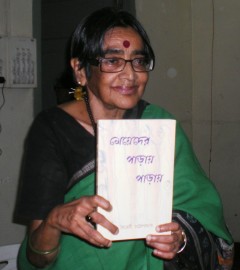

She was an omnipresent woman, who would travel all the way to Rajasthan, Patna, Mumbai, Jaipur and even into the interior of villages in West Bengal to research her stories. The last compilation of her works Meyeder Padaye Padaye (Bengali, which translates to 'in the neighbourhood of girls') was published by Search, and released on International Women's Day last year. That was her last appearance in public before she fell seriously ill. The book offers a fragmented glimpse into her incisive articles spanning over more than a decade of publishing in dozens of print media outlets in Bengali or English.

She, along with Saswati Ghosh was invited to be Guest Editor of the Pooja issue of Bibhab - normally edited by Samarendra Sengupta - in October 1991. The edition dedicated entirely to women, was a sell-out not leaving a single issue for archivists and researchers. Among her other publications are Bandhon Chhendar Sadhon, published by Pratikshan and Baandh Bhenge Dao, brought out by Emancipation.

She began her career in journalism as a music critic, and was extremely well-versed in the grammar of music and art. But even in this aesthetic space, she committed herself to focusing on women. She wrote in-depth pieces on women musicians, early women writers of Bengal and women in theatre. Her three articles on the late Mira Mukherjee, one of the most outstanding sculptors of the country, shed light on many unknown aspects of the artist's philosophy, including her extensive research for months on the subject she would next cast in her sculptor's mould.

Maitreyee-di writes how the sculptor passed away not having been able to realise her dream of sculpting a 14-feet high idol of Gautama Buddha, an effort into which Mira Mukherjee put a long period of research before she set her hands to shape the image in her mind. Maitreyee-di details how this great artiste would hold classes for children of daily labour and rickshawallahs in the small verandah of her home, and allowed their creativity to flow freely; how she persuaded poor families to allow their grown girls to copy these designs on kantha cloth in embroidery by helping their families with cash and kind.

In an article in Basudhara published in February 2005 entitled Chooncher Phode Tulir Taane ('With the pierce of the needle and the sweep of a paintbrush') Maitreyee-di underlined the social mainstream's complete sidelining of ordinary housewives' artistic contribution to folk-art like the alpana, kantha embroidery, patachitra, etc. on grounds that they were part of their daily household chores and therefore, remained beyond the periphery of recognised and widely accepted works in the world of art.

She began her career in journalism as a music critic, and was extremely well-versed in the grammar of music and art. But even in this space, she committed herself to focusing on women.

One incident comes to mind while discussing Maitreyee-di's rich contribution to academic knowledge of various things. An article in The Statesman had drawn and quartered former Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpeyee by calling him a beef-eater. The PM wrote back to say he would rather die than eat beef. (The Statesman, 21-22 February). This exchange set off a minor war in the media universe of Kolkata, besides being a spectacle of the usual sort for the lay observer. However, it was Maitreyee-di who stole the show - with a letter to the editor (published March 7, 2003), pointing out both the concerned parties' complete ignorance of history while they dueled today.

She wrote, "A study of history and an examination of ancient Hindu scriptures and other literary works establishes beyond doubt that not only was beef tolerated as an article of food in Vedic India, but that the sacrifice of cows, calves and bullocks was enjoined as an act of the higher religious efficacy." In support of her argument, she quoted from Hindu scriptures explained by Raja Rajendralal Mitra in his monumental work (The Indo-Aryans, Vol.I, Chapter VI). The letter illustrates the painstaking research that went into a simple letter to the editor of the very paper in which she was a regular contributor.

She was the Founder Member and Convenor of Nari Nirjantan Pratirodh Mancha (Forum against the Oppression of Women), one of the first rights-based women's groups in Kolkata in 1983; the organisation continues to play a significant role in the women's rights movement in West Bengal. In the 1990s, the Uniform Civil Code controversy and issues like state and communal violence on women brought all independent women's organisations of the country together to find resolutions. An All-India Workshop on Gender Just Laws was organized in Mumbai in 1996 in which Nari Nirjantan Pratirodh Mancha presented a position paper on the Uniform Civil Code.

The paper was collated out of many meetings organized by the Mancha with everyone, including Maitreyee-di, presenting their views on the subject. She travelled to Mumbai for the conference as a representative of the Mancha. Talking of traveling, friend and peer Mira Roy says that Maitreyee-di always either walked or travelled by public transport. She never used a taxi or a car and for long distance travel, the train was her best friend.

She was vocal in her criticism of the government at the Central, State and District levels and did not run shy of calling a spade a spade. In an article titled "Hell's Angels" (The Statesman, 9 December, 2001), she slammed the condition of the inmates of government-run homes for women - such as the Liluah Home close to Howrah - following a spate of attempted suicides and the rape of a deaf-mute inmate. The article also pointed an accusing finger at the West Bengal State Commission for Women. This brought an angry response from Jasodhara Bagchi, who then headed the West Bengal State Women's Commission. Not one to take things lying down, Maitreyee-di wrote a detailed rejoinder presenting statistical data in support of her anger.

Interestingly, a few years later in 2006, the same Commission under the same Chairperson felicitated Maitreyee Chatterjee for her contribution to the cause of marginalised women and children!

But she didn't do it for the awards and felicitations. What mattered to her was addressing issues of human rights from which women and children remain excluded in practice though they are written in law. She fought gender discrimination in society, politics, administration and occupation beyond the home, and she railed against violence that women everywhere endured.

From Rupan Bajaj to Archana Guha who were imprisoned and subjected to inhuman torture in police custody for many years, to Ratandevi, Hamibai, Shanta Behn and Bhanwari Devi of remote villages of Rajasthan, to Mithu Roy, a victim of unconstitutional imprisonment, Maitreyee-di's pen was a constant friend to all. It worked like the edge of a sharpened knife - cutting, slicing, quartering and mincing the powers that were, who she held were responsible for the wrongs.

Her feet and grit took her wherever she was determined to go to find out the truth, to fight, to rebel and to raise awareness among women. Her words

and voice took her even further - and they remain alive through her writings and through the innumerable activists she nourished, educated and trained

to fight for their own rights and for the rights of other women.