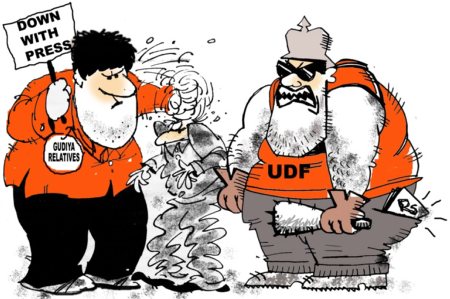

On November 1 at Kozhikodes Karippur Airport, media persons had recently attempted to cover the arrival of P K Kunhalikutty, a Muslim League (ML) minister in the United Democratic Front Government in the state. The minister is facing charges of the rape of a minor girl, and was returning after a haj pilgrimage. The party had organized an official reception; senior ML party leaders including an MP and a minister were present.

What transpired was something else. A frenzied crowd brought there by the Muslim League beat up more than a dozen media persons, some of them receiving severe injuries and their equipment completely destroyed, causing huge losses. The hoodlums chased press persons in full view of the police who maintained a determined inactivity. For more than three hours the ML crowd were seeking out particular journalists -- M P Basheer of India Vision, one Deepa of Asianet and M P Prasanth of Indian Express -- who exposed the charges made by Rejina, a young Muslim woman.

Regina had openly spoken about Kunhalikkutty's sexual assaults on her in 1996-'97, when she was a minor. Kunhalikkutty was Industries Minister in the previous UDF Government at that time. Rejina had also admitted that she retracted her earlier accusation in the court only because she faced much pressure as the powerful politicians who assaulted her had bought over even her own family members.

![]() It appeared the hoodlums were given a specific agenda and sufficient training to carry out the media-bashing. They were reported to have declared that the media ought to be taught a lesson. They were carrying lathis, sticks and missiles, though ostensibly they came there to give a heros welcome to the minister.

It appeared the hoodlums were given a specific agenda and sufficient training to carry out the media-bashing. They were reported to have declared that the media ought to be taught a lesson. They were carrying lathis, sticks and missiles, though ostensibly they came there to give a heros welcome to the minister.

The incident at Karippur has already had its fallout all over the State and pitted the entire media in Kerala against the Government. But several serious issues need to be discussed, including some of the medias own failings.

First, there is a striking similarity between what the national media faced almost 12 years ago in the ancient city of Ayodhya when they witnessed the Kar Sevaks pull down the Babri Masjid and what Keralas media received at the Kozhikode Airport. At Ayodhya, the zealots had taken special care to chase away the media, beat up many newspersons and destroyed camera equipment so that the world will not see what they were doing.

At both places the zealots claimed they were representing religious groups, waving saffron flags in Ayodhya and green flags in Karippur. In both cases, the attacks were calculated, and the media as an independent organization was being targeted for the legitimate role it played in informing a democratic society.

Also, the governments response to Karippur is the similar to what happened after Ayodhya. When Babri fell and the media was running for cover, Prime Minister Narasimha Rao was taking his famous afternoon nap. No one dared to rouse him and he came to know about it at his evening tea. His great follower, Keralas Chief Minister Oommen Chandy was up and about but he chose not to raise a hand against the Muslim League or his minister. In fact, the Additional Director General of Kerala Police, Mr. Alphons Erayil, has given a report to the Chief Minister acknowledging that there was enough police force at Karippur to quell any violence. The ADGP has found fault with the Superintendent of Police and other officials.

But when the Kerala Union of Working Journalists (KUWJ) leaders met the Chief Minister this week demanding action against the culprits on the basis of the ADGP's report, the Chief Minister said that he would not take any action then because he had ordered a judicial inquiry into the incidents. The state government has taken a stand that the media had overstepped its role in its campaign against the minister. But that charge does not stand scrutiny. In a media atmosphere as highly competitive as we see in Kerala, matters like assaults on women involving politicians are bound to get extreme media attention. So the standoff between the media and the state government remains, leaving the issue unresolved.

Second, police in Kerala are being turned into accomplices in politicians criminal actions. Media persons are being intimidated for carrying out their rightful role in covering these events. After the Karippur assaults, this author met most of more than a dozen media persons who were hospitalized for three days; the government did absolutely nothing to help them out and no one from the state government bothered to meet them. The Chief Minister and his council of ministers were more concerned about the displeasure of Muslim League as the party held the key to the stability of the present UDF Government.

But in its unwillingness to take act firmly to protect media persons, the government is sending out a message that bashing media is legitimate, and that it condones the hoodlums and the polices inaction.

Third, the past few years have seen a rise in the instances of attacks on the media in Kerala, despite the states citzenry having a high level of political awareness, powerful media houses and deep media penetration. The attacks have generally gone unchecked, and even unchallenged. In the Muthanga case, the media had to face the consequences for their bravado. Police had fired on the Adivasis who took possession of forest lands; one Adivasi and a policeman had died in the confrontation. The media was there -- Asianet and Kairali had their camera teams on the spot. They debunked police claims of Adivasi rioting with visual footage that actually proved the police atrocities.

But at least one journalist, Ramdas Mannaroth of Asianet, had to face criminal charges of conspiring to murder in a case that police registered following the firing. It took almost two years of litigation with immense financial losses and harassment for Mannaroth to extricate himself from the case. He did not receive any support from his employer.

Four, harassment and financial losses pose serious operational problems for journalists working in the regional or moffusil newspapers. There are a large number of newspapers and a concentration of visual media organizations covering news in the state. Few organizations provide a respectable salary or even necessary equipment to their staff, worried about capital losses during violence.

Some years ago, when the Congress-led Youth Congress members beat up almost a dozen media persons covering their violent rally in Kozhikode, the KUWJ district unit (the author was president of the unit at that time) found that the losses to the camera and other equipment came to around Rs.60,000. It turned out then that except for a few powerful media houses, no employer was actually giving even a camera to their news photographers. Many photographers owned their cameras; any damage to their lenses or camera meant the loss of their livelihood because their employers failed to give any financial support to them.

Attacks on the media are therefore a deeper problem than mere physical threats. Perhaps it is high time media houses themselves or the government come up with an insurance scheme to provide support to the newspersons for losses from the hazards of work in Kerala. The national media also has to give more attention to these recent incidents than they currently are.

The recent Gudiya marriage controversy was virtually televised on screen by a north Indian channel. Rejinas story in the media was also the torture of a woman in public involving politicians, police, media and a ruthlessly intrusive society. It seems the ethical norms on reporting practices evolved through decades are longer valid in these competitive times.

Still, Keralas media have taken up a campaign to preserve their right to report on the developments, the issue being one of freedom of expression. The medias call must be heeded, but the media must also develop self restraint and respect for human dignity and decorum.