Gumri today is known to motorbike aficionados and car drivers as the checkpost near Zoji-La Pass on the highway that connects Srinagar in Kashmir to Leh in Ladakh. It is here that most travellers, after having zig-zagged through the steep cut in the mountains, pull over and click photographs of the awesome surroundings that mark a complete divide in topography. But long before the convoy of army vehicles, bike riders and cars, there were the kafilas - caravans of camels, mules and horses - carrying traders along this historic route, as a photograph by Italian geographer and explorer Giotto Dainelli depicts.

This photograph, taken in 1904, is housed along with several other artefacts at the Munshi Aziz Bhat Museum of Central Asian & Kargil Trade in Kargil town. It is a rich testimony to the fact that far from being an isolated region, Ladakh was once an important centre of trade. And Kargil, which many people heard of only during the 1999 war, has a much older and far more fascinating history.

Ajaz Hussain Munshi, chief curator of the museum which houses his family's legacy of the trade, explains to me how Kargil, situated on the banks of the Suru river, developed as an important epicentre.

Home to many tribes and cultures, Kargil, he points out, is 210 km from Leh, 220 km from Baltistan, 200 km from Zanskar and 214 km away from Srinagar. In fact, the very name Kargil is derived from Garkhil, which means a place where one takes a halt from all other places. This key geographic location enabled Kargil to develop as an important trading post for Central Asian trade which flourished for centuries. Much of the trade went in the direction of Yarkhand in the Xingjiang region. Yarkhand became a major trading centre along the Silk Route and an important distribution centre.

The transcontinental and multi-directional trade along the Silk Route used camels, horses, mules and yaks to form caravans. These caravans carried silk, spices, wool (pashmina), jewellery, ceramics, opium and other narcotics. In return the traders from Yarkhand brought back manufactured goods like soap, cosmetics, matches etc. It was largely a trade meant for the elite classes.

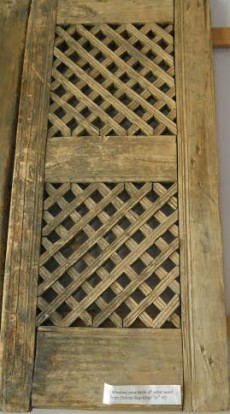

In 1998, Ajaz and his brother Gulzar Hussain Munshi decided that the old dilapidated building which had been in the family should be completely razed. They were unaware of the buildings rich history as a serai or even what it housed. Fortuitously a mason chanced upon a turquoise in the building and informed the family. (Pic: An old window frame made of cedar wood dating to 18th century)

One such person was Ajaz's grandfather, Munshi Aziz Bhat, who began his career as a patwari or record keeper in the revenue department. He quit in 1915 to begin his own business and soon established himself as a leading figure in the Central Asian trading business along with his two sons and a cousin. In 1920, he constructed a larger serai in Kargil along the banks of the Suru river to further his trading contacts with the Balti, Chinese, Tibetan and Hindustani traders. The three-storied serai building had stables for the horses and other animals, a large basement, a kitchen, a depot and other rooms where goods could be stored.

The formidable mountains and high passes had not proved to be a major obstacle but with Partition and the closing of borders, this historical and flourishing trade came to an end. According to Rizvi's book, the last caravan crossed the Karakoram in 1949 and the serai, like the trade, fell into disuse.

The members of the family were forced to take up other careers. In 1998, Ajaz and his brother Gulzar Hussain Munshi, who is presently Director of the museum, decided that the old dilapidated building which had been in the family should be completely razed for construction of a commercial complex. They were unaware of the building's rich history as a serai or even what it housed. Fortuitously a mason chanced upon a turquoise in the building and informed the family.

"My father, who was ill and in bed, told us that there were many such possessions and goods lying in the basement of the serai. It was also around this time that a researcher Jacqueline Fewkes sought an appointment to meet us, saying she had letters in her possession from my grandfather. After she met us even my father was enthused and we realised we had perhaps an amazing array of trading goods which would provide rich insights into the lives of the traders and the culture that had evolved."

It was thus that the family museum was set up in 2004 to showcase this legacy. Artefacts unearthed from the serai were exhibited along with contributions by families and people from Leh who had in their possession objects that were part of memory of the Asian trade.

Rugs and carpets of Central Asia at the museum.

Among the artefacts housed in the small room of the museum are British horse saddles and goods associated with the transport animals, woollen carpets and rugs from Kashgar, dresses of traders of various nationalities, guns and other fire-arms, textiles, old coins and currency, cooking utensils, crockery, items of jade, hookah pipes and so on.

Photographs including those by William Moorcroft, the explorer who was employed by the East India Company, help reconstruct and bring alive the vibrant past. Some of these artefacts were even displayed at an exhibition in Delhi's India International Centre in July 2010.

"Lack of space hinders us from displaying all the artefacts we now possess and hope to get," explains Ajaz Bhatt. The family wants eventually to create a trust

which will serve as a repository that highlights the manner in which the Central Asian trade made possible, not just the exchange of goods and culture, but also a

free flow of ideas. They hope this will enable national and international researchers to keep alive a vibrant slice of history that was in danger of being erased

because of the changed geo-political scenario.