Information is my right.

Safia Sircar writes about how sustained public pressure is

bringing greater transparency to the panchayats of Rajasthan.

May 2001 :

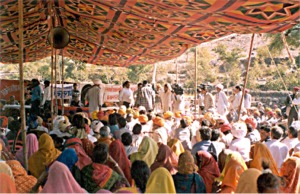

Gomti Churaha was crowded. Thirty-seven tents

completely filled. It was show time for the villages.

The call for public accountability in the form of the

jun sunwai had been given by the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti

Sanghathan (MKSS).

But a moment, to refer to the back pages of 1996. Then, a 40-day dharna was held at Chang Gate in Beawar. That launched a long peoples struggle and campaign for transparency of government functioning and the people's right to information. A group of women and men of the MKSS initiated the movement. The philosophy to right to information is simple. “The right to know is the right to live”. In its forty days the dharna was sustained by the people of Beawar and the 300 villages in which the MKSS worked with contributions in kind, cash and time. Four hundred organisations (the number is growing) gave their support. The dharna gave birth to the National Campaign for People’s Right to Information (NCPRI).

The Bori jun sunwai, held in Dec 1999

So April 3, 2001 saw the jun sunwai, one of the most powerful public tools to bring corruption to forefront. Figures unearthed by the MKSS speak for themselves. For 98 works done in past six years from 1994-2000 in 10 villages, labour expenditure came to Rs 52 lakhs and material expenditure to Rs 48 lakhs. Total expenditure comes to Rs one crore (or if you want the exact detail Rs 1,00,75,341.) Evaluation could be done for 31 works out of 98 due to incomplete records or late arrival of information. Yet for the evaluated Rs 65 lakhs, the villagers and the MKSS discovered that Janawad’s panchayat officials and bureaucrats had siphoned off around 45 lakhs!

Despite there being a 1996 Panchayati Raj State ruling as well as the Rajasthan State Right to Information Act, information regarding the Janawad panchayat accounts has not been easy to come by for the villagers. On repeated attempts, the Block Development Officer (BDO) promised that the information would be given in five days. Fed up, the MKSS approached the State Panchayati Raj secretary and the Collector. On December 30, 2000 the panchayat secretary arrived. He came not with the information but with a stay order from the Jodhpur High Court, not to release information. The Court stayed the release release of information on grounds of disturbing peace. But barely a month later, on the January 29, 2001 the Court gave its permission.

The Court reversed its stance after the MKSS made representations giving details from both the Rajasthan Right to Information Act as well as the Panchayati State Act of 1996. The sarpanch, the BDO and the District Commissioner (DC) released the panchayat accounts of Janwad panchayat covering a period of five years. Finally, armed with the information they sought, the MKSS and villagers organised the April 3 hearing. According to the Act, the records should have been made available within four days. That’s theory. In reality, the villagers got the information after a year-long struggle.

The exposition of April 3, was followed by a national convention on April 5 and 6 at Beawar. This convention was organized to observe five years of the right to information movement in Rajasthan. Beawar occupies a special place in the history this movement, because it was from this very place that the campaign had been launched in April 1996. During this period, the movement has successfully pressured the State government to enact an enabling legislation that nevertheless remains weak in several respects.

On April 6, the Rajasthan Chief Minister arrived. Seven questions were asked concerning the administration’s intentions on the drought situation, the right to information and women’s issues. After his speech, the CM walked off the stage without answering. A strategically placed banner stared starkly at him. It screamed boldly “paani do, roti do, naukri do nahin tuo gaadi chodh do” (Give us water, food and jobs or else leave the chair.)

The Beawar Declaration was then read out. It expresses the questions that need to be answered in the minds of the people on issues below:

-

Drought and chronic hunger:

In a situation of widespread hunger amidst plenty, people do not know why such a situation has arisen. What resources are available with the State? Why are these not being made available to the people? What are the State’s responsibilities under the famine code? What are the State’s plans and what has been actually done to provide food and generate employment?

-

Displacement:

Millions of internal refugees have been displaced by large projects and urban development plans. The nature if the public purpose, the details of acquisition and rehabilitation should be actually shared with affected people.

-

Health:

There is huge inequity in quality and access to health services; corruption and complete lack of accountability of the health administration compounded by mystification by health professional. Information for health services needs to be available at village, block and district levels.

-

Education:

Deep structured inequities in the education system are enabled also by lack of information and accountability. People need to know the performance of the State.

-

Human Rights:

Most human rights violations, especially against poor and marginalised women, men, dalits, tribal people and minorities, occurs behind opaque walls of police stations and jails. These bastions need to be thrown open to public scrutiny and accountability.

-

Electoral Politics:

The electoral system needs to have information and provide this to the public. For instance the assets and criminal cases filed against all candidates seeking election to public office should be available to the people.

-

Judicial Accountability:

The judiciary’s language and legal system needs to be people oriented. The performance of courts at all levels including speedy disposal of cases and assets held by the judges should be made available to people.

-

Media:

The assets, business linkages, land other facilities received from the government or corporates, political affiliations of media houses, journalists, utilisation of newsprint and circulation figures should be given to people.

-

NGOs/Civil Society Organisations:

The NGOS need to be genuinely accountable to the communities they work with. For instance they have to place accounts, assets of Board and staff members and performance reports.

-

Nuclear and Defence Establishment:

Budget allocation, expenditures, purchase decisions, military and nuclear strategy, health impacts and safety standards should be brought into public domain.

-

Globalisation and Economic Development:

The livelihoods of poor people, especially in the countryside have been critically compromised by a series of international agreements, which have been reached with absolutely no public debate or even information. Similarly, large public assets including in the power sector are being sold and restructured without even minimal public scrutiny.

-

Women:

It is the State’s responsibility to actively inform women about their land rights, reproduction, health rights, right to information and other vital entitlements. Women have to be informed about their rights and rights need to be strengthened.

-

Laws on the People’s Right to Information:

The central and state governments should further safeguard the Right to Information, by enacting strong laws. These laws should not only cover the State, but also the corporate sector, the judiciary and NGOs. They should have minimal exemption clauses, penal provisions for wanton default and independent appeal mechanisms. In, addition, the State should have not only have an obligation to inform people when they so demand it, but must positively share information which is used for their survival and well-being.

On April 9, after the jun sunwai and the convention, three of the culprits were arrested, the ex-sarpanch, the gram panchayat sevak and one of the junior engineers. This is the first time that such action has been taken immediately after a public hearing. The Rajasthan government has since assured the MKSS that a special team will be constituted to do a detailed investigation.

Safia SircarMay 2001 Safia Circar is a New Delhi based journalist