The mind goes back to all those kinds of ‘gaze’ today as one reads and watches with great pain the devastation in Uttarakhand over the last several days. I feel forced to review the different types of ‘gaze’ over the long journey of this State (created after a great popular resistance), all of which have combined to lead to this catastrophe of the present. The ‘gaze’, of course, is far older than the State of Uttarakhand itself.

Many people loved the mountains. For many reasons. And from that love emerged the gaze. So, you had the tourist gaze; the business gaze; the adventure-tourist gaze; the NGO gaze; the romanticist gaze, and of course the religious-pilgrim gaze. Some who loved the mountains went as conquerors, scaling the highest peaks and setting up mountaineering clubs, taking with them more adventurists like themselves - each peak scaled a new trophy to impress people with, their selves and egos gleaming with pride following every successful expedition.

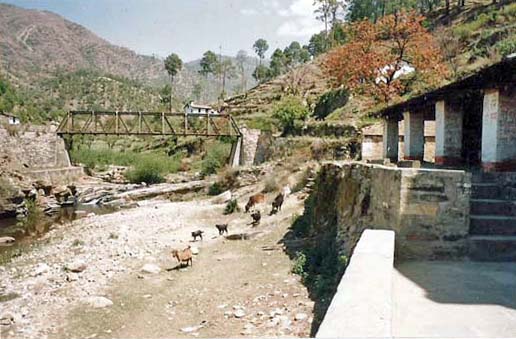

The landscape in the Kumaon region of Uttarakhand. Pic: R. Uma Maheshwari

Some others who loved the mountains (city dwellers, mainly) bought pieces of land - small, medium or large, depending on what they could afford - for a piece of its quiet to run away to when the city got to them (strangely, these were ones who never quite left their cities once and for all, and would go back to the same often, when the mountains and the quiet got to them). Later, some of them opened up resorts that would in time come to be known as ‘eco-resorts’; expensive, because they were ecologically friendly, in fact pretty ‘niche’. Others founded NGOs. This helped them maintain the lifestyles they had become used to - a little bit of creature-comfort coupled with the luxury of the mountainous beauty around them. The funded NGO entities enabled them to enjoy the moral protection of political correctness.

In the decade of the 80s and early 90s, NGOs mushroomed in the hills of Uttarakhand. By the end of the 90s, post-economic restructuring, power projects and tourism (‘eco’ or not so ‘eco’) thrived across the Kumaon and Garhwal regions of Uttarakhand (though Tehri dam has a longer story).

And there were those, who loved the region, not for the mountains per se, but for the gods and goddesses that resided in them, almost always in the most inaccessible of all places, so that reaching the god or the goddess was always an adventure. It also symbolised the larger meaning of how difficult it was to navigate the maze this world signified before reaching a level of union with the unseen. Of course, the difficulties mid-way made this annual ritual a business proposition for others; people hoarded in thousands in unregulated for-profit activity. Some of them also operated “off-season” tours for ‘less’ in seasons when you should ideally not be navigating through the mountains at all.

So, there were all kinds of mountain lovers. With their own respective gazes. They gazed only at the exterior beauty, the resources, the awe-inspiring, exalting element and either ‘took from’ or returned. The gaze itself was external.

• How we ignored the obvious

• Beware of disaster profiteering

![]()

Missing the woods for the trees

The intensity of relationship with nature - which included people, animals, birds, trees, forests, clouds, the night skies, the constellations, the mountain peaks - was either absent, or ill-understood.

Weren’t there also human societies and histories within these mountains? NGOs, pilgrim tourists, adventure tourists, and finally the private money makers actively collaborating with the state on unrealistic numbers of power and mining projects seemed to notice only what was external and extraneous about the mountains; they saw the visible facets, not the living layers. They were rarely deep, hardly intense.

In cases where such intensity did exist, in some people, you found them living as islands unto themselves, taking in the beauty and serenity of the mountains, oblivious to the world around them. At the same time, it also did create people who gave up everything and remained in these environs, engaging positively with the place, either as political or social activists. But the numbers of such have always been, and still remain, few.

Were the mountains merely nature’s bounty, or did they have other facets? Did their beauty become their curse attracting all kinds of gaze and consequently leading to the destruction we witness today, which may or may not be reversible?

I, too, went to the mountains over and over again. For I too, loved them. And I similarly took in their beauty, and the abundant, overwhelming nature, which to me was also reflected in the generosity of the people who stayed there. To me, like to other romantics, as one crossed the last town of the UP foothills and plains to enter the hills, the people seemed always more friendly, always hospitable, loving, kind, and welcoming (especially to a woman, travelling alone). I, too, saw in the mountains only that which was superficial or extraneous; I, too, assumed that people living in the midst of this necessarily imbibed or internalised the magnanimity of the rivers, the mountain peaks, the tall cedar trees and Indian oaks. I overlooked the fact that even here were pockets of claustrophobic social contexts for women, tribal communities and the lowest castes.

Subjugation of women is as much a reality in the hilly interiors as anywhere else. Women can be seen breaking backs from dawn to dusk. Pic: R. Uma Maheshwari

Subjugation of women is as much a reality in the hilly interiors as anywhere else. Women can be seen breaking backs from dawn to dusk. Pic: R. Uma Maheshwari

These were the far-too-self-contained local pockets that you saw only within the depths of the mountains, if you travelled within these pockets and trained your eyes for more than a singular kind of gaze. Then, you would see the oppressive caste system in place, and women’s subjugation and all as dreadful, as exploitative here, as in the rest of the world we ran away from. What was idyllic in nature did not always extend to the idyllic in human social contexts. Women, tribal people and the lower castes were the most oppressed, worked twice as hard as others, were respected little and had rituals in place as regressive as elsewhere. Traditional livelihood options were forcibly removed so many took up whatever was offered. So, what were these mountains and hills all about? Were they (not) more than what they seemed at first glance or several first glances?

Now, the gaze is back on the mountains. This time around, the gaze is likely to dwell longer than before, since we now have ‘24x7’ media. This time, it is the disaster-tourism gaze and the strangely pathetic gaze on ‘my pilgrims’ that state governments are focusing on. Again the gaze is from the outside, unconnected to the local context, unresponsive to it, apathetic to it. People of Uttarakhand do not figure in this frenzy.

Looking within

But what has the gaze got to do with floods or the current devastation in Uttarakhand?

That is relatable in the context of how we look at development, at tourists, at places, at pilgrimages. Thanks to the several kinds of gaze, the mountains or the roads to the mountains of Uttarakhand never slept, unless a freak incident halted journeys mid way. This time around it has been halted in a big way.

Ironically, in all of the decades that have seen so many flocking to the mountains, little has changed for the local mountain-dwelling communities of the lower classes or castes or for the tribal communities. Their plights continue to be the same. Little changed for them even as their lives got intricately linked to those of the settlers or travellers that invaded their spaces, either for the love of the hills or for extraction from them for profit. Everyone has extracted a bit from the mountains and their people, and nature, bit by bit. But very few have truly concerned themselves with these interiors, its minerals and other resources. People’s lives here - already as fragile as the eco-system they lived in - were made more fragile and even dependent on such extracting gaze.

Many lives rest on bridges & across streams in the mountains that we do not even see. Pic: R. Uma Maheshwari

What these mountains and their environs needed were social revolutions of various kinds, not ‘developmental intrusions’ in the form of power projects, road construction and the like, forced from above and disconnected from all that was endemic to the region. More cash only meant further consolidation of the existing prevalent inequities in spite of the sprouting of thousands of NGOs. Radical politics hardly found favour or long term space (though in the early 60s and 70s, the Left parties had a strong base in these regions) because of the nexus between the polity, business community and the funded NGO movement. Taken together, this did its bit to kill popular resistance.

In Uttarakhand, as elsewhere, there have always been local people who have played an equally important role in making the State what it is today; many local contractors, mafia and others, earn from the current development course in the mountains which is far from sustainable. And why should it be surprising, anyway? In fact, starting now, we shall perhaps see new groups sprouting in the midst of the old, taking advantage of the disaster and making plans to provide a permanent ‘resettlement’ package as a funded exercise that may or may not reach the truly vulnerable local people.

The destruction now may still be less grave than the permanent one being caused over a longer-term to not just Uttarakhand, but all those that are delicately linked to the Himalayan eco- system outside the region of Uttarakhand.

What then would be the best way to rebuild or help rebuild, people may ask, besides charity and aid? Perhaps, it would be to send in petitions in millions, to put a curb on all the hydel projects and extractive profit-making enterprises in this region, including adventure and pilgrim tourism (at least the latter can be regulated), until the region regains its spirit. In spite of the deceptive promise of employment that these bring, they keep the people bound to a course of development that has myopic vision at best. The mountains and the entire eco-system need real help this time that goes deeper beyond the transient, superficial ‘gaze’ that it has received so far.