Bilaspur, July 2002: By the time the first contractors arrive at the narrow, crowded chowk of the old Sanichari to pick up their quota of daily labour, the sun is already high up over the eastern expanse of the Arpa river swamp. And Hemantibai of Chateedee, Jalbai of Dabripara and Karibai of Chingrajpara have already spent the entirety of their morning waiting. Their turn will not come, they know, if ever it does, till mid-morning after the swarms of young men have been taken and then the old men and the young women.

No, the reason they arrive at the Sanichari labour market as early as they possibly can, after preparing the day's meal for the sons and husbands who remain behind, is to find a place to sit. Today and most days the only seat available, the only place they can rest their aging bones in preparation for the day's punishing labour - without fear of being chased away by surrounding shopkeepers - is this tiny parapet over the overflowing drain. They do not mind the smell anymore or the flies.

Between them, the three women together have spent a lifetime in the casual labour market. Yet the best season, they say, is the month of Karthik, the marriage month in October-November. Then they can earn up to Rs 100 a day. In the rest of the year, for eight hours of carrying brick and cement and stone, they earn Rs 40 daily. And that is on the days that work becomes available. The contractor gets Rs 50 for each labourer but normally he passes on the full amount only to the men. The confiscated Rs 10 can be thought of as a penalty of sorts - the double burden of being old and being a woman. If one accounts for the Rs 30 daily shortfall relative to the minimum wage for unskilled construction labour, we also have an estimate of the price these women pay for their illiteracy.

On the sliding scale of the slum economy Hemantibai, Jalbai and Karibai are not the worst-off of the elderly. They still have the social net of a family and most importantly, the use of their limbs. For those without these aids the slide into destitution and further can be precipitous.

The ambitious provisions of the much-heralded 1999 National Policy for Older Persons remain by and large on the drawing board stage. And even a casual glance at the statement of facilities/benefits given to senior citizens by various ministries/departments reveals a preponderance of tax rebates and transport fare concessions, targeted largely to upper income groups. The senior citizens of Chingrajpara are unable to benefit from the largesse of the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Railways, the Ministry of Civil Aviation, or even the venerable Ministry of Rural Development. They go begging in the alleys of the slum, depending instead on the more reliable munificence of their humble neighbours.

I. The Bachelor

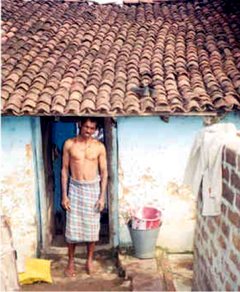

![]() Raghuram Lodhi. Old man's life in a rented room. Pic: Ashima Sood

Raghuram Lodhi. Old man's life in a rented room. Pic: Ashima Sood

Raghuram Lodhi, who is somewhere in the vicinity of 60, lives alone in a rented room at one end of the Asha Abhiyan's phase I area. (Asha Abhiyan is a slum development project, initiated in the early 1990s by Harsh Mander, then Bilaspur's Commissioner. It was reinitiated in Chingrajpara during his tenure as the Country Director of ActionAid India.) On the afternoon that I meet him, he is resting in the dim, dark fanless six-feet-by-six interior, listening to a rusty six year old transistor. After some coaxing he is finally persuaded by his neighbour Seeta Gupta (Slum Diaries II) to tell his meager tale.

Raghuram goes to work as a construction 'coolie' in the Sanichari, earning a daily sum of Rs 70. The figure he quotes is higher than the women at Sanichari for several reasons chiefly his gender and the higher skill jobs available to him as a man. But on average he manages to find a day's work only about 20 days out of the month. Though Raghuram does not make the connection, there is one to be made. Although the casual labour market setup at the Sanichari does not guarantee a livelihood even to the young men that throng the chowk, it is easy to observe the casual ageism that pervades transactions there. The highest paid jobs, from offloading railway freight to transporting coal, are reserved for those with the brawn power for them. The earliest trucks that leave the Sanichari each day carry away the young.

Raghuram finances the slack with the surplus of the other days. His daily expense on a twice-a-day meal of rice and dal that he cooks himself comes to Rs 20-30. And then there is the monthly rent for the room. In all his years in Chingrajpara, Raghuram has not acquired a ration card.

In his telling however Raghuram shies away from the one central event that explains, he later confesses, the bulk of his circumstance the desertion of his wife, a few short years after his first arrival in Chingrajpara 25 years ago, leaving him alone to raise two daughters. His dream now is to return to his village of Patharia Dakachaka where he still has half an acre of land, much reduced after financing his daughters' weddings. As the price for taking care of their aging father however his daughters, one of whom lives in Chingrajpara demand that Raghuram sell his land. It is a demand that Raghuram is still able to resist.

The 1991 census found that as many 60.5 percent of India's 17.8 million males over 60 years continued to be in the workforce. The National Sample Survey, 52nd round of 1995-96 further reported that a majority of urban elderly males (51.5 per cent) claimed they were not dependent on others.

Still, Raghuram does not dwell on the solitariness that is his lot. The social isolation that is elsewhere described as the central concern in the situation of the elderly remains a luxury of sorts for the likes of Raghuram. The comfort of his transistor seems to be sustenance enough.

II. The Beggar women

The higher life expectancy that is the one demographic trump card women hold in India is in many ways an unenviable one. Its most significant fallout is the burden of widowhood one researcher (Bose in Seminar, April 2000) estimates the incidence of widowhood among women of 60+ to be 54 percent as against only 15.5 percent for men in the same age group. Further the vulnerability increases with the decades after 60 - 46.3 percent of women are widows in the 60-69 years, followed by 66.1 in the 70-79 age group and 69.8 in the age group 80+.

To understand the import of these figures it is instructive to note the workforce participation rate for 60+ females a mere 16.1 percent. As many as 87 percent of elderly urban females are fully (75.7 percent) or partially (11 percent) dependent on others. Though the percentages are slightly more in rural than in urban areas and more for men than for women, in all the family supports about three-fourths of all elderly persons.

What happens when these normally durable ties of family become attenuated? Consider as a case study, the beggar women of Chingrajpara.

Dhuli Sahu, who her neighbours claim is no less than 65 years of age, is one of them. She sets out early morning 8 o'clock once in every three or four days on a round of the slum to collect whatever offerings her neighbours can spare for her some rice, or dal or vegetables and a few rupees, sometimes 2, sometimes 4. This has been her only livelihood for close to nine years. Even though she counts among her assets the land title or patta to her shack, a BPL (Below Poverty Line) ration card, obtained last year through the good offices of her neighbour Geeta Sahu (Slum Diaries II), and no less than four living offspring, including two sons, one of whom lives right next door.

The origins of her present circumstances Dhuli traces back to her husband's death 10-11 years ago after a lifetime of casual labour and zero savings. Or perhaps it was the leprosy that snared her before that. She has been treated, she claims, through a lengthy regimen of needles and pills, which she was very careful to follow. But her son and daughter-in-law still mistreat her and even beat her on occasion. Sometimes her aching back and legs keep her home for a week or more it is only after she has gone hungry for a few days that her daughter-in-law deigns to give her one measly meal.

Despite her impenetrable Chhattisgarhi, Dhuli is eager to share the woeful details of her life. Lately she has been losing her eyesight the doctor recommended surgery but since her medical card tore, healthcare has been very expensive. Though Dhuli probably only got the benefit of the medical card in the first place as part of the National Leprosy Eradication Campaign, the woes of old age, the arthritis and rheumatism, the cataracts and declining eyesight find her now without health care she can afford. She depends instead on the occasional support of neighbours.

Kokilbai Lodhi, who to the best of her knowledge is somewhere between 65 to 70, lost her eyesight gradually over the last fifteen-twenty years. That is also how long she has lived in Bilaspur, after being driven here by the drought that struck her village Soti, the drought that perhaps also claimed her husband. It was the villagers she says who arranged his funeral. As reticent as Dhuli is garrulous, Kokilbai also speaks a thick dialect that is no easier to comprehend than her neighbour's. Her mouth is twisted in a kindly elderly expression it is only with time that one realizes that it is not a smile but a grimace.

Kokilbai has had an eventful life she bore six children, four of whom did not survive into adulthood; she was married to one man and left him for another. Now her youngest son, the one she arrived with in the city, the only one who stayed with her thus far has abandoned her. After years of petty labour and begging, Kokilbai was hoping at last to be supported by her offspring. But instead the boy got married and decided to disappear. At the end of her life, Kokilbai is left "an orphan of old age", with no one to call her own.

Kokilbai shuffles through the narrow alleys of the slum with her cane in one hand and her begging bowl in the other, trying hard to appraise the world with dim eyes. Even so, her step faltered some time ago and she fell in to a drain. Bhagwan Lodhi and his wife Kamla (Slum Diaries II & III), her caste people, came to her rescue and paid for her treatment, two kori, Rs 40 per doctor visit. (One of the many interpreters nearby explains that one kori is equivalent to Rs 20.)

On the day I meet her, Kokilbai is preparing the few leafy vegetables she was able to receive on her trip today, in celebration of the local festival of Hariyali, harvest season. Unlike Dhuli, she does not have a ration card she does not have the money for it, she says. She goes on her round everyday or tries to anyway. However like Dhuli, she does get some form of old age pension for the destitute elderly, roughly Rs 150 per month, every three months or so.

Even more open is the question of how far such a wide-ranging social security net is financially feasible given a graying population. According to United Nations projections, the elderly will account for 12.7 percent of the population and by 2050, 21.3 percent. Although both the Cr.PC as well as the Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act 1956 uphold the legal right of destitute parents to be supported financially by better-off children, few parents are willing or able to take family matters to the law courts. *

In many ways the status of the elderly in Chingrajpara is inseparable from larger political economy issues the livelihood matters that beset the elderly are often a continuation of the income insecurity that plagues their most productive years. One of the more practical solutions offered is under Project OASIS 'Old Age Social and Income Security' that aims to harness the minimal savings capacity of unorganised sector workers in a contributory pension plan. A government appointed expert committee report on Project OASIS had said that if invested wisely, regular savings at a rate as low as Rs.3-5 per day through a person's entire working life can help escape destitution in old age. However the report, presented to the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment in January 2000, has still not reached the implementation stage.

As the Dhulis and Kokilbais hobble through their neighbourhood, begging bowl in hand, their most dependable resource continues to be the generosity of their neighbours, the desire for a destitute's blessing.