The demand for real estate, particularly near the Mumbai shore, is extremely high – reaching upwards of Rs. 1 lac/sq ft in some cases. Builders, in collusion with venal politicians and bureaucrats, will go to tremendous lengths to secure such precincts, known as koliwadas, after the coastal Koli community.

Insensitive planners have their fair share of the blame for posing a threat to these villages. A draft 20-year Development Plan (DP) from 2014-2034 ran roughshod over these villages, among many other tricky places, and public pressure saw its outright rejection. A new plan is on the anvil.

The proposed Rs 12,000-crore road, which will be reclaimed along the city’s western seashore, causes grave concern not only to the homes but also to the livelihood of the fisherfolk.

The Mashal study

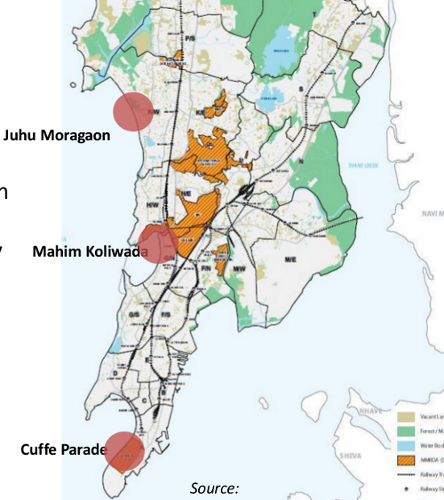

A parastatal body, somewhat grandiosely titled the Mumbai Transformation Support Unit (MTSU), commissioned a Pune-based NGO called Mashal, which works on urban issues, to study how the reclamation of the past, from 1970 to 2011, had affected the lives and livelihoods of three representative koliwadas : Cuffe Parade, Mahim and Juhu, running from south to north Mumbai.

Mashal pilot study sites at Cuffe Parade Koliwada, Mahim Koliwada and Juhu. Pic: Maharashtra Machhimar Kruti Samiti (MMKS)

One wonders whether the undisclosed agenda is to lay the ground for the redevelopment and possible rehabilitation of these villagers, in the wake of huge infrastructure and real estate projects.

The tone and tenor of the launch by MTSU of the Mashal study was made evident by the opening remarks of B.C. Khatua, who heads MTSU. “All interventions are not necessarily against nature,” he opined, areas could be affected but mitigated by human action. Indeed, he continued, natural areas could be “enhanced – you can have your cake and eat it too.” This was why Mashal was asked to map the three areas.

This study on land reclamation in development projects between 1970 and 2011 was launched in June this year, but has still not been made public, possibly due to the drubbing it got from city activists and fisherfolk representatives – particularly from the Maharashtra Machimar Kruti Samiti (MMKS), a formidable force to reckon with.

As in many areas of public life, there is confusion over the most basic of statistics – the actual number of koliwadas in the city. The Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) puts it at 24. The Department of Fisheries census estimated it was 30, while the MMKS, quite understandably, arrived at the higher figure of 37.

As Americans say, if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it. A detailed paper on proposals and demands for koliwadas for the abortive DP by Shweta Wagh and Hussain Indorewala, who teach at the Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute for Architecture and Environmental Studies, cites the Census of Marine Fishermen by the Department to show that there are at least 33 active villages, with some 1,65,000 people dependent on fishing and related activities.

Cuffe Parade koliwada

Mashal comes up with surprising statement that reclamation in the Cuffe Parade koliwada, at the southernmost tip of Mumbai, has actually been “beneficial for fishing as exposure to the sea has increased”.

Mashal states that the notorious massive reclamation in the 1960-70s, under a corrupt Congress government led by Chief Minister V.P. Naik, to create Nariman Point (ironically named after the nationalist leader who opposed such reclamation early in the 20th century!) and Cuffe Parade, the new central business district, destroyed mangroves to accomplish this task.

Mashal mentions that fishing was reduced as a consequence, but in 1977-78, the Revenue and Forest Department offered the community a 4,555-sq-metre plot close by to compensate for their loss. It records: “Since the current location was more appropriate for fishing, the community refused to shift to newly offered site. There was also opposition from local residents for it.”

It is difficult to justify reclamation anywhere for enhancing fish catch. Anyone who visits the area can see that the Cuffe Parade koliwada is hemmed in on one side by high-rises, which will considerably cramp the style of the community.

In the immediate future, Mashal lists three potential threats to this koliwada :

1. The enormously profligate Rs 2,000-crore Shivaji statue, one of the tallest in the world, to be erected on reclaimed land in Marine Drive Bay, the most iconic setting of Mumbai.

2. Land will also have to be reclaimed for jetties to enable visitors to reach the statue. As it notes, “The reclamation along with the buffer zones around the statue island and Raj Bhavan island would narrow the approach way for the fishing, affecting rock-based fish production.”

3. Currents will also shift, affecting the catch.

In answer to questions during the launch, Mashal stated how urbanisation had actually increased the sale of fish, but youth were no longer interested in pursuing such an arduous occupation and sought other pastures. Some residents said that the reclamation had not affected fishing, but older residents confirmed it had.

In 1974, environmentalists rallied against the rampant reclamation of Backbay and submitted an alternative plan by Charles Correa to “freeze” the bay as it was and encourage leisure activities along its edge. Naik called a halt to the reclamation, but the blueprint was never implemented.

Mahim koliwada

Mashal is equally equivocal about the Mahim koliwada. The new central business district of Bandra-Kurla was reclaimed from mangroves in 1970, choking the mouth of the Mithi river which empties out into Mahim bay.

Between 1990 and 2000, housing for project-affected people was constructed on the reclaimed areas. This was followed by a huge sewage treatment project, an outfall into the sea. It cost Rs 1,000 crores, with a $192 million loan from the World Bank. However, without treating the sewage, it merely carried it a few km into the sea and released it there. (This writer served on the committee to monitor its environmental impact.)

As indiaenviromental portal noted at the time: “[The project] is facing the wrath of environmentalists and fisherfolk in the city, who contend that the project is not environment-friendly…”

The fisherfolk also pointed to the contamination of marine life in Mumbai’s coasts and creeks. Bhai Bandarkar, president of the MMKS, and an executive member of the National Fishworkers Forum, said, “The Mumbai Municipal Corporation is the largest creator of pollution in Mumbai. The sewage in Mumbai goes untreated into the sea and the creeks around the city, thus poisoning them and the fish.”

Mashal makes the extraordinary claim that land reclaimed for the sewage project led to the formation of a fisherfolk-friendly natural beach, through interference with natural patterns. It says: “Though the land was reclaimed to constructing the sewage treatment plant, over the years the Koli community was benefitted due to the beach formation which is used for drying yard, boat parking.”

In the same breath, it admits that “informal settlement has proliferated too. Because of these constructions, narrowing of the river, the effects of the 26 July 2005 [mega] flood in this area were immense.”

It doesn’t mention that the reclamation for the Bandra-Worli Sea Link also constricted the Mithi, which backed up and spilled into the inner recesses of the city, causing death and destruction.

Juhu-Moragaon koliwada

Mashal observes that between 1988 and 2000, within 500 metres off the coast, an area called Mora Sai Baba was bought by a developer in Juhu-Moragaon koliwada. Slums came up and it was registered as a society for an official redevelopment under the state’s Slum Redevelopment Authority. By 1993, a residential building came up there.

As Mashal states, the fisherfolk lost three-quarters of their income “due to reduction in mangrove areas, narrowing of creek and water contamination”.In 2005, a pumping station was constructed to prevent waterlogging by demolishing 165 Koli houses which had been built to accommodate their growing population.It points out that “no land was allocated for the koliwada for their fishing activity or housing. With prime functions developing in the vicinity, the community land is under developer pressure.”

A far more pointed critique of this koliwada was made by Rajesh Mangela, secretary of MMKS, who was present at Mashal’s launch. It says that the previous DP of 1991 recommended the pumping station to help builder Kiran Hemani of the Future Ready group push back the high tide line – 500 metres from which no construction is permitted.

In a recent article titled “The long road to progress” Mangela tells the Hindu: “Everybody wants to stay along the coastal area; why can’t we? It is our right. Like everyone, we also want clean air and a nice environment. Why should we move? Does the coast only belong to judges and ministers? You should ask them how they made their money. We live a life of dignity here.”

The fate of the Kolis

At the Mashal study launch, Mangela cited a 2015 study by the Delhi-based Rajeev Gandhi Institute of Contemporary Studies which found that the 2005 floods were compounded by the extensive construction carried out by blocking the course of the river Mithi and three other city rivers.

“Land reclamation has thus affected the natural ecosystem, like mangroves and fishing activities, and Kolis are one of the most-affected communities by various phases of such land reclamation that have been going on since the colonial period in Mumbai.”

Elsewhere, in the coastal area of Versova, MMKS cites how land was denied to Kolis while buildings have come up on marshes and mangroves for IAS officers and even an apartment complex for judges, in a blatant violation of the central Coastal Regulation Zone notification of 1991.

Plot in Versova coast where IAS officers and judges have built on mangroves: Pic: Maharashtra Machhimar Kruti Samiti (MMKS)

Mangela cautions how the proposed coastal road, which Mashal only mentions in passing, will reclaim land for real estate or club houses, while reducing the fish catch since the breeding rounds will decrease drastically. The 170 hectares of open space reclaimed for the road, it fears, may be usurped for gardens for the elite, like Priyadarshini and Joggers parks in the city. This will only increase the pressure on koliwadas.

Wagh and Indorewala say, “Urban fishing villages have been under a sustained threat of redevelopment and renewal, as they are located in one of the most desired parts of the city – its coast. Fishing villages are not simply housing, rather they are strikingly self-contained as urban units, with livelihood opportunities, homes, markets, cultural and social institutions, all integrated within a compact and walkable district.”

Their take is that redevelopment of these villages to build commercial complexes, large institutions and housing is unsustainable, exclusionary and quite mindless as it is these forms of development that are threatening to eradicate these villages.

Wagh and Indorewala add, “As a crucial part of the city's built and unbuilt heritage, the DP of the city must make provisions to protect and support its urban villages.”

Mashal does make recommendations to protect koliwadas as exclusive residential neighbourhoods with commercial activities like seafood restaurants and calls for a Fishing Industry Master Plan. However, without making a much sharper analysis of the existing pressures by vested interests, the study doesn’t add up to much.

At the launch, Debi Goenka from the Conservation Action Trust, asserted that reclamation was in fact banned since 1991 and wondered if MTSU had already decided that it was good for development.

In view of the fact that the MTSU supports the coast road, the question hangs over the fate of koliwadas, the homes of Mumbai’s original inhabitants.

REFERENCES

Study of Land Reclamation in Mumbai: Phase 1 (1970-2012), S. Gandhi, D. Mukherjee and S. Srivastava, Department of Geography, Mumbai University, 2014, also commissioned by MTSU.