Ever since the AAP's win in Delhi, there have been a spate of articles on right wing websites, questioning the rationale of issues that form the core of the AAP's political ideologies. One is the issue of subsidies and the other is the idea of Swaraj -- of decentralisation of political power and governance-related decision making authority to local governments and indeed, to the people themselves.

Speaking of the idea of Swaraj, as envisioned by the AAP, it must be remembered that so far, with the BJP and the Congress at the helm of affairs, there has been no concerted, pan–national pressure in India to decentralise power and responsibility and strengthen Local Governments. True, we have a federal system that on the face of it looks fairly robust.

While the Central government collects 66.2 percent of all government taxes, it only spends 47.7 percent. States collect 31.3 percent of all government taxes, but incur 45.2 percent of all government expenditure, (because they receive a share of the central revenues, based on the recommendations of the Central Finance Commissions). It is only when we come to the local government system that our reluctance to decentralise becomes quite clear.

Municipalities and Panchayats collect only 2.5 percent of all government taxes and incur only 7.11 percent of all government expenditure. Neither the BJP, nor the Congress has taken steps to set right this terrible fiscal imbalance. They have only gone to the extent of creating the structure for local government through the 73rd and 74th amendments, but have kept them on a starvation diet of finances.

Women at a rally in Bangalore (2012) to demand devolution of funds, functions and functionaries to Grama Panchayats. Pic: The Concerned for Working Children

The key difference between other political parties (particularly those of the right) and the AAP is their varying commitment to real decentralisation of power and responsibility to sub-national governments, including Panchayats and Municipalities. An appreciation of history underscores that modern India’s approach to strengthening and empowering LG systems has been fitful.

Parties such as the Congress and the BJP have in the past bandied about a lot of rhetoric on decentralisation, yet they have taken little action on the ground. Such rare action, too, has been taken only because in both parties, there happen to be a few loyal flag-bearers who show unstinted loyalty to the concept of people governing themselves.

These believers write reports recommending one or the other reform, the powers that be make the appropriate sympathetic noises, make a few changes in the law and then continue with business as usual when it comes to the fiscal architecture, which remains highly centralised. This cycle is repeated every now and then, particularly when work on preparing the national five-year plans (FYPs) is on.

Are we ready for swaraj?

The mainstream parties cannot be blamed. They are only reflecting the views of most Indians. We, the voting citizens of India, have not demanded decentralisation of power and responsibility.

There could be two reasons for the lack of a desire among some Indians to have a more decentralised political structure in India. First, our constitutional design is of a “holding together” federation, where our sub-national entities, the states that constitute the union of India, are themselves creatures of the very union they constitute. We are not a “coming together” federation, where once independent and sovereign states consent to come together, transform themselves into sub-national units of a federation and devolve upward some of their powers to the national federal government.

The Indian approach results in the union determining how much power ought to be vested in the states and not vice versa. Residual powers vest in the union. Thus, our form of federalism has strong centralising overtones and the shadow of centralisation looms large over local governments and conditions their behaviour. They tend to see themselves as institutions at the bottom of a tiered government structure.

Second, conditioned by this centralising constitutional design, many Indians are wary of too much of heterogeneity, or independence, in governance. “Coming together” federations are often comfortable with diversity and celebratory of it. On the other hand, too much of celebration of diversity—be it a demand that primacy be given to a certain culture, way of life or language—is often seen in India as a dangerous trend, endangering the unity of the country.

This attitude subliminally conditions many modern Indians to accept centralised power more readily and the notion that government is tiered. We do not seem to realise that governments could be relatively autonomous within their spheres of functioning. We perhaps believe that even a demand for more decentralised governance, if it goes beyond certain limits, could be perceived to be anti-national.

The flip side of the reluctance to seek self-governing rights is the acquiescence to the idea of being ruled by a higher level of government. We are more likely to accept being ruled than seek the right of ruling ourselves. Even when we militate against bad governance, we prefer to demand that our existing rulers govern better, rather than seek the right to govern ourselves.

Seen in the light of this sobering reflection, we might better understand why the constitutional provisions concerning Local Governments have not been effective—we have not sought that they be effectively implemented.

Can decentralisation focus be a workable political strategy?

So far, in the absence of pressure from below to decentralise, the pace of devolution of powers and responsibilities downwards has been critically dependent on individual champions. Experience shows that they have been very few, both within mainstream political parties and within the bureaucracy.

In our competitive political system, pursuing an agenda of decentralisation is a doubtful strategy for aspiring leaders seeking upward movement in party echelons. Established politicians of these mainstream parties do not have much motivation for pushing decentralisation as their political mission. If people see them as messiahs in any case, there is no great gain in pushing for power to the people; it does not bring them further political capital.

Similarly, strong bureaucrats do not see pursuing a decentralisation agenda as holding much potential for career growth. Thus even when political signals have favoured decentralisation, actual progress has always been hamstrung by weak administrative action.

But then, with the victory of the AAP, the issue of decentralisation has now become a political issue. The AAP's stand on Swaraj is now being taken seriously, because it is the one party that actually has a concrete agenda on how it will go about making people central to the idea of participatory governance. Now, for the first time, people seem to be conscious of the idea of Swaraj and seem to have voted for that.

Earlier, as long as parties such as the BJP and the Congress only mouthed the idea of decentralisation and did not show any inclination of actually putting this into practice, people from the ruling elite were not too worried. However, now that the AAP actually promises to deliver on this promise of decentralisation, many people are writing substantive articles to question that idea.

That is a very good thing by the way, because the extent to which India needs to be decentralised, will only be enriched through debate. At least, now, with the advent of the AAP, the substantive issues that need to be discussed are emerging from the cloud of rhetoric that used to surround the issue of decentralisation, in India.

Where does AAP stand?

Speaking of local government, the future political strategy of the AAP needs special deliberation, especially after what Yogendra Yadav told volunteers of the party on the direction that the party might take. Since I am particularly keen to see the party make a mark in local governments and also because Bengaluru city is going to have its civic elections held shortly, my attention is drawn to the prospects of the party in urban areas.

According to the Census 2011, India’s urban population is around 377 million, which is 31.17 percent of the total population. Though these people live in 7935 urban areas, only 4041 are statutory towns, legally defined by States as ‘urban areas’, and therefore governed by the provisions of the 74th amendment.

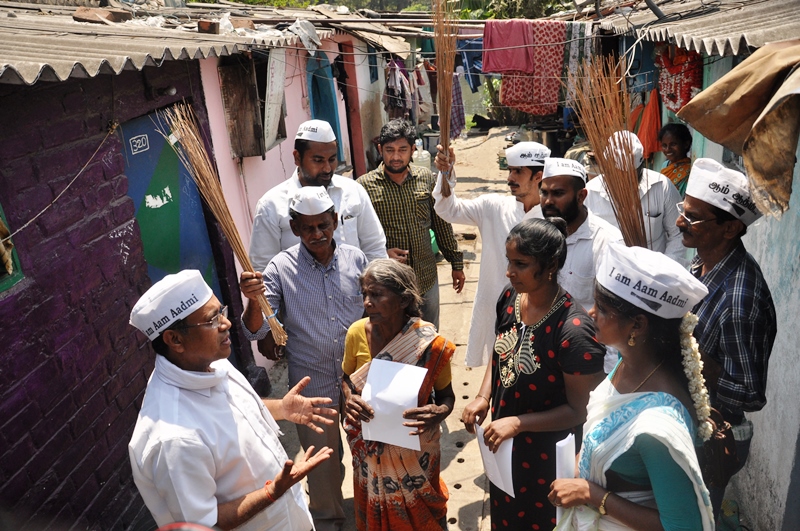

An AAP candidate meets voters in New Delhi during the poll campaign. Pic: aamaadmiparty.org

The remaining are ‘urban’ in character as per the census definition, namely, more than 75 percent of the population in these areas are engaged in non-agricultural occupations.However, on the law books, they continue to be villages and are governed by the provisions of the 73rd amendment.

There is a great skewedness in the spread of urban population. Though there are 7935 ‘urban’ areas, of which 4041 are ‘statutory towns’, only 55 cities have a population of more than one million people (This number is now estimated to have crossed 65). However, these 55 cities have a combined population of 166 million, which comprises 42.6 percent of the urban population.

Local government elections are different in nature from State and Central elections in many ways. A key difference is in the scope of the reservation of seats for various categories of people. In the Lok Sabha and Vidhan Sabha elections, seats are reserved for SCs and STs, as determined by a delimitation commission as may be established from time to time. However, in the local government system, not less than 33 percent of seats are reserved for women.

Within this sub-category, there are separate reservations for SC and ST women. In addition, the Constitution provides flexibility to States to provide reservation for women belonging to the Backward communities and minorities as well.

Looking at the dramatic rise in the influence of the AAP in Delhi, one of India’s largest metropolises, I began to focus on the electoral potential of the AAP in other metropolises as well. In doing so, my hypothesis is that urban areas, and within them metropolises, provide the greatest scope for the expansion of the AAP. This would also enable the AAP to touch the lives of a large number of people who live in these areas. (By the way, by saying so, I am not precluding the possibility of expansion in rural areas and smaller town as well).

Now let us look at the statistics of the number of seats in the 54 metropolises listed in the 2011 census (excluding Jamshedpur, which is an Industrial township and has no elected representatives).

In 20 cities in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Haryana, J&K, Rajasthan, Telengana, Tamilnadu, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal, where the reservation for women is at the minimum mandated level of 33 percent, there are 1821 seats on offer, 609 of which are reserved for women.

However, in metropolitan cities in the States/UTs of Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Chandigarh, Delhi, Gujarat, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Orissa, Punjab and Rajasthan, where the reservation for women has been increased to 50 percent, there are 3138 seats in total, of which 1569 are reserved for women.

In total, India’s 54 metropolises, comprised of 166 million people or nearly one-sixth of the population, offers 4959 seats in their municipalities; of these, 2178 (a share above 43 percent) are reserved for women.

Now here are some interesting points to note. It was the Congress that introduced reservation for women in local governments, through the 73rd and 74th amendments. Later on, it was the non-congress governments – starting with Bihar in 2006, that increased the reservation to 50 percent. The Congress governments in States, realising quickly the political advantage in enhancing the reservation of seats for women, followed suit.

However, who actually gets to stand for elections from these reserved seats? If you look at the behaviour of the mainstream parties in India, regardless of all their professed commitment to ensuring that women are represented in adequate numbers in local governments, more often than not, party candidates for these seats happen to be the wives, sisters, or mothers of the men who are denied tickets because these seats happen to be reserved. True, there are exceptions, but they only serve to emphasise that the norm is to give tickets to women who are proxies for politically powerful men.

Before I pursue my line of argument any further, may I emphasise that I am in no way disparaging the women who make their initial foray into politics as proxies of men. There are several I personally know, who have battled prejudice, control from home and many other impediments to climb out and make their own mark in politics.

However, the fact still remains that for self-made women political workers in the mainstream parties, it is extremely difficult to secure the party ticket to stand for election. More often than not, they lose out to the women relatives of powerful men as the party echelons consider the latter to be more ‘winnable’.

It is here that the AAP could make a difference. Being a new age party, it is, hopefully, free of these typical prejudices. There are several women in the party who are better than the men, in local campaigning, in influencing voters and in political skill. This was brought home to me in telling fashion the other day when I was walking around with an AAP team.

‘You men’, I was told, ‘always talk of the larger picture; of Arvind Kejriwal and what is happening in Delhi. Women from the AAP speak to us about our problems – the lack of water, sanitation and safety, and commit to provide solutions’. Clearly, women seem to be having much greater influence amongst voters in the build up to the local government elections.

The party also needs to introspect on what has made mainstream parties engage in double speak when they implement the vision of inclusion of women in democratic representative politics, so that the AAP can avoid these.

All mainstream parties want to gain the political goodwill that goes with the announcement of reservation of seats for women – the same that drove the strategy of giving a constitutional recognition to reservations and its enhancement to 50 percent. But then, these parties are also full of condescending males and their real attitudes are seen in how they exclude women for organisational positions within the party. When the party organisation itself is male dominated, women reservations are captured by the proxies of politically powerful men.

I only hope that the AAP will not go down the same route. It must ensure that in Mission Vistaar, its currently ongoing party organisation-building effort, at least 50 percent of party organisational positions are given to women. It is only when women control the party, that the reservation of seats for women in local governments will have any real political meaning.

The AAP has a huge opening here. They must not lose it.